Impact 2007: Personalising learning with technology

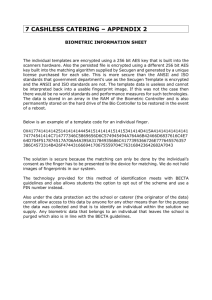

advertisement