Word - Nature Works Everywhere

advertisement

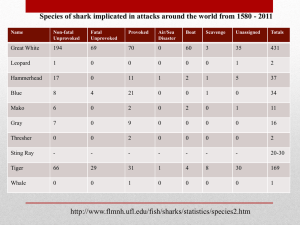

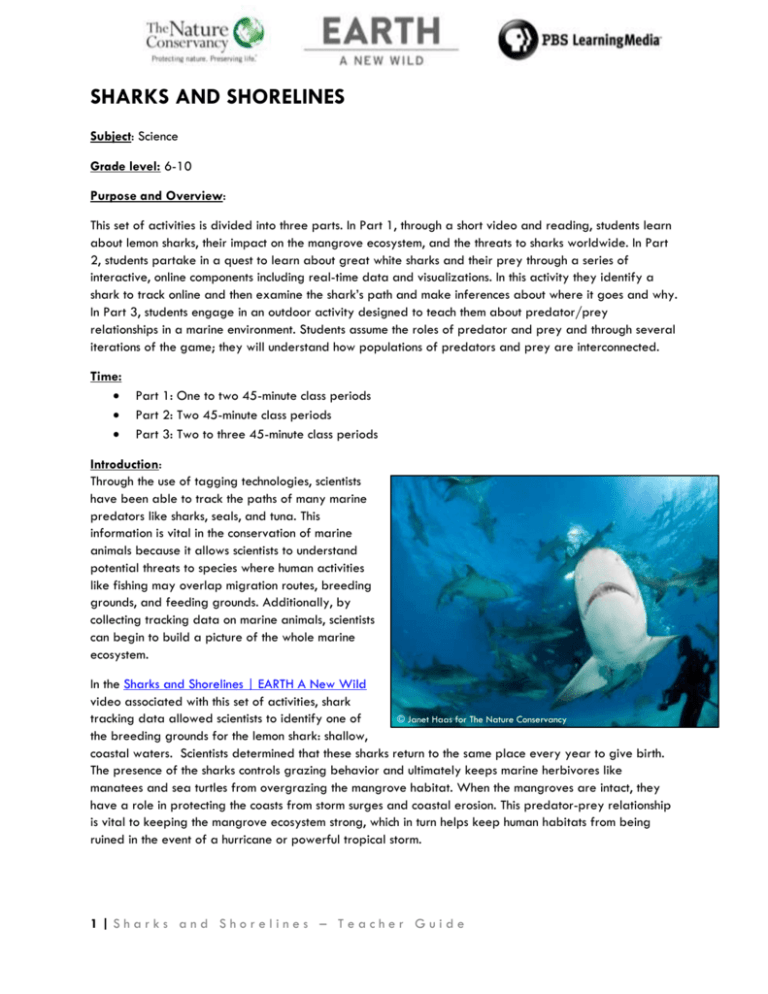

SHARKS AND SHORELINES Subject: Science Grade level: 6-10 Purpose and Overview: This set of activities is divided into three parts. In Part 1, through a short video and reading, students learn about lemon sharks, their impact on the mangrove ecosystem, and the threats to sharks worldwide. In Part 2, students partake in a quest to learn about great white sharks and their prey through a series of interactive, online components including real-time data and visualizations. In this activity they identify a shark to track online and then examine the shark’s path and make inferences about where it goes and why. In Part 3, students engage in an outdoor activity designed to teach them about predator/prey relationships in a marine environment. Students assume the roles of predator and prey and through several iterations of the game; they will understand how populations of predators and prey are interconnected. Time: Part 1: One to two 45-minute class periods Part 2: Two 45-minute class periods Part 3: Two to three 45-minute class periods Introduction: Through the use of tagging technologies, scientists have been able to track the paths of many marine predators like sharks, seals, and tuna. This information is vital in the conservation of marine animals because it allows scientists to understand potential threats to species where human activities like fishing may overlap migration routes, breeding grounds, and feeding grounds. Additionally, by collecting tracking data on marine animals, scientists can begin to build a picture of the whole marine ecosystem. In the Sharks and Shorelines | EARTH A New Wild video associated with this set of activities, shark © Janet Haas for The Nature Conservancy tracking data allowed scientists to identify one of the breeding grounds for the lemon shark: shallow, coastal waters. Scientists determined that these sharks return to the same place every year to give birth. The presence of the sharks controls grazing behavior and ultimately keeps marine herbivores like manatees and sea turtles from overgrazing the mangrove habitat. When the mangroves are intact, they have a role in protecting the coasts from storm surges and coastal erosion. This predator-prey relationship is vital to keeping the mangrove ecosystem strong, which in turn helps keep human habitats from being ruined in the event of a hurricane or powerful tropical storm. 1|Sharks and Shorelines – Teacher Guide Part 1: Lemon Sharks and Mangroves Grades: 6-10 Subject: Science Purpose: The purpose of this activity is to introduce students to the role that lemon sharks play as predators in a marine ecosystem and to relate the behavior of lemon sharks to the preservation of the mangrove forest and the protection of our coasts. Students will also learn about the threats to sharks worldwide and how tagging helps in conservation efforts. Time: One to two 45-minute class periods Materials: Teacher - computer, internet access, LCD projector Sharks and Shorelines | EARTH A New Wild video (3:56 min) URL: https://vimeo.com/116273821 Copies of student worksheet for Part 1 (located at the end of this document) Small whiteboards or sheets of drawing paper and markers Student copies of the National Geographic article “Blue Waters of the Bahamas” URL: http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/print/2007/03/bahamian-sharks/holland-text Optional – student access to computers to explore interactive content for the shark ecosystem URL: http://www.pbslearningmedia.org/resource/5aeed659-7f0b-417f-81d95f2e9c747644/ecosystem-explorer-earth-a-new-wild/ Objectives: The student will…. List the ocean herbivores that can impact a coastal ecosystem. Describe how sharks maintain the coastal ecosystem through intimidation behavior. Identify how the tagging of sharks helps scientists to learn more about their behavior. Relate how tagging data improves shark conservation efforts. Describe how humans are impacted by the sharks’ presence. Illustrate the threats to sharks worldwide. Predict what would happen if sharks, an apex predator, were removed from an ecosystem. Evaluate how humans can help conserve sharks. Next Generation Science Standards: Disciplinary Core Ideas: LS2A Interdependent Relationships in Ecosystems LS2B Cycle of Matter and Energy Transfer in Ecosystems LS2C Ecosystem Dynamics, Functioning, and Resilience LS4D Biodiversity and Humans Crosscutting Concepts: Cause and Effect Stability and Change 2|Sharks and Shorelines – Teacher Guide Performance Expectations: Middle School MS-LS2-1. Analyze and interpret data to provide evidence for the effects of resource availability on organisms and populations of organisms in an ecosystem. MS-LS2-2. Construct an explanation that predicts patterns of interactions among organisms across multiple ecosystems. High School HS-LS2-6. Evaluate the claims, evidence, and reasoning that the complex interactions in ecosystems maintain relatively consistent numbers and types of organisms in stable conditions, but changing conditions may result in a new ecosystem. Vocabulary: Bycatch: fish or other organisms caught while actually fishing for another species or target fish. Ecosystem: a biological community of organisms interacting with the biotic (living) and abiotic (nonliving) components of their environment. Finning: refers to the removal of shark fins while the remainder of the living shark is discarded into the ocean. Shark fins are in high demand in some parts of the world for use in shark fin soup and traditional cures, in which shark fins are an ingredient. Because fins are worth a lot of money compared to the rest of the shark, fishermen can collect more fins if they harvest them while at sea and throw the rest of the shark overboard. Sharks with their fins removed cannot swim and will eventually perish. Herbivore: an animal that eats plants. Longline fishing: a deep-sea, commercial fishing technique in which a really long line (often several miles long) with baited hooks spaced at intervals is used to catch fish; also called longlining. Longline fishing can have serious consequences for sea turtles and sharks when they are caught as bycatch. Sea birds are vulnerable when the longlines are set because they are attracted to the bait. Mangrove: a tree or shrub that grows in coastal swamps that are flooded at high tide. Mangroves can protect coastlines from erosion and flooding. Predator: an animal that preys on or eats others; sharks are predators. Prey: an animal that is hunted and killed by another animal for food. 3|Sharks and Shorelines – Teacher Guide Suggested Flow for Part 1: Section A: Video Viewing Guide 1. Distribute copies of the student worksheet for Part 1 so that students can answer the video viewing questions while they are watching the Sharks and Shorelines video. Go over the questions with students so they know what to look for during the video. 2. Show students the video and then give them time to complete any questions on the worksheet that they were unable to answer and then go over questions with the students. 3. Be sure to emphasize with students that the sharks’ presence in the mangrove acts as a deterrent to herbivores like sea turtles and manatees. This is called intimidation behavior. Simply by swimming around, the sharks discourage herbivory, which is what ultimately helps keep the mangrove forests and sea grass communities going strong and these healthy communities provide habitat for a wide variety of marine organisms. Humans benefit because the mangroves can help prevent coastal erosion and flooding. 4. Optional activity: If you have access to student computers, it may be useful to provide students with another opportunity to interact with the shark story. The “Ecosystem Explorer” was inspired by content from the EARTH A New Wild series and includes a “Shark World” where students can explore the shark ecosystem through interactive, multi-media content. You can find the interactive content here: http://www.pbslearningmedia.org/resource/5aeed659-7f0b-417f-81d95f2e9c747644/ecosystem-explorer-earth-a-new-wild/. If time doesn’t permit, you could assign this as homework. Part 1 Student Worksheet - Video Viewing Questions Answer Key 1. In the video, scientists are shown tagging different ocean predators. What kinds of data can scientists collect from the tags? Answer: The tags data can tell scientists when are where the sharks are moving. Scientists can determine key migration routes, breeding grounds, and feeding grounds. 2. How does the tagging help with conservation? Answer: It helps pinpoint the areas that might need to be protected. Tagging also shows movement and distribution patterns, as well as biological hot-spots, so that the culling of marine populations can be done with much more sustainable foresight. 3. What have researchers learned about lemon sharks through tagging? Answer: Lemon shark females return to their birth places to give birth to new young. 4. What does the mangrove ecosystem provide for organisms? Answer: It provides food and shelter for a variety of young marine organisms. An “underwater nursery.” 5. How do sharks maintain the mangrove ecosystem? Sharks regulate feeding behavior of prey. Herbivores are less likely to eat as much vegetation when they are on the lookout for sharks. 4|Sharks and Shorelines – Teacher Guide 6. List some examples of marine herbivores. Answer: Manatees, sea turtles, some species of fish 7. How do the sharks help humans? Answer: The mangroves decrease powerful waves that hit the shores during storms. Just by swimming in coastal waters, sharks keep the mangroves and sea grass areas healthy by preventing overgrazing. By protecting these areas, we are protecting shark nurseries and the sharks help protect the mangrove, which in turn protects our vulnerable coasts. Section B: Threats to Sharks 1. The purpose of this part of the activity is for students to read more about the sharks around Bimini in the Bahamas and learn about some of the threats to the sharks there and elsewhere in the world. If you have time for students to read an article to learn more, they can do the following reading and white-boarding activity. If you want to introduce students to the threats that sharks face worldwide, but are short on time, you can show the video, “Collapse of Sharks” (3:05 minutes), which examines the demand for shark fins in the Far East and describes the resulting decrease in shark populations. URL: http://www.pbslearningmedia.org/resource/nat08.living.eco.humeco.collapse/collapse-ofsharks/ 2. Distribute copies of the three-page National Geographic article “Blue Waters of the Bahamas” by Jennifer S. Holland and have students read the article. They can do this in class or for homework to save class time. 3. After students have read the article, assign them to small groups of three to four. 4. Distribute white boards or large sheets of drawing paper to each group. 5. Read off the first question and give students two to three minutes to do a very simple illustration for this topic. Emphasize that it does not need to be a work of art – stick figures will do. There should be no text accompanying their drawings. The groups can talk through what should be drawn and elect a student to do the drawing or they can all share the task. If you have access to small whiteboards, give one to each group for their drawings. If not, use large sheets of paper, or have students do this in their notebooks in small groups. If you have access to a document camera, students can project their drawings. The purpose behind using drawing for this activity is for students to synthesize the information from the text and not to copy from the reading when answering a question. 6. Once the time is up, have all of the students hold up their drawings and have the whole class look around and see what was drawn. Have each group elect a speaker to explain their illustrations. By having students hold up their drawings, you can quickly assess how the students have interpreted the reading and other students can check their answers against the rest of the class. Students may have drawn different things and that will allow the class to see the different interpretations of the article as well as the similarities. 5|Sharks and Shorelines – Teacher Guide 7. Repeat this process for every topic in the list below. Topics for illustrations: According to this article, what are the biggest threats that lemon sharks face? Drawings may include fishing, long-lining, finning, human development Why are mangroves being threatened in the Bahamas? Drawings may include buildings, boats, marinas, casinos How would the depletion or removal of an apex predator, like the lemon shark affect the marine ecosystem. Drawings may include sharks eating other fish that are eating algae on coral reefs. 8. After the rounds of drawings are complete, conduct a final discussion and ask the students to share ideas about how humans can help sharks and marine ecosystems. Student answers may include managing the number of tourists and creating marine protected areas. Other Resources for Part 1: Information on the biology of Lemon Sharks: http://www.elasmo-research.org/education/ecology/estuaries-lemon.htm Shark facts and information on how The Nature Conservancy is working to project sharks: http://www.nature.org/ourinitiatives/habitats/oceanscoasts/sharks.xml 6|Sharks and Shorelines – Teacher Guide Part 2: Track a Shark! Grades: 6-10 Subject: Science Purpose: The purpose of this activity is to give students a chance to investigate the life of a great white shark using real tracking data from an online source. Students will also analyze other data to determine the reasons behind shark migration. Time: Two 45-minute class periods Materials: Teacher – computer, internet, LCD projector Copies of student worksheet for Part 2 (located at the end of this document) Internet with access to http://www.ocearch.org/ website Computers (one per student is ideal for this activity, but you could also group students on computers) Objectives: The student will… Describe the movement of sharks using an online tracking tool. Analyze the movement of sharks based on tracking data, sea surface temperature, and other factors. Relate shark movements to the geography the East Coast of the U.S. and the sea floor of the Atlantic Ocean. Identify areas where sharks and humans may come into contact. List the threats to sharks and describe how tagging data can help shark conservation efforts. Evaluate information and create a statement to explain the reasons behind shark migration. Next Generation Science Standards: Disciplinary Core Ideas: LS2A Interdependent Relationships in Ecosystems LS2B Cycle of Matter and Energy Transfer in Ecosystems LS2C Ecosystem Dynamics, Functioning, and Resilience LS4D Biodiversity and Humans Crosscutting Concepts: Patterns Cause and Effect Science and Engineering Practices: Asking questions Analyzing and interpreting data Constructing explanations Engaging in argument from evidence 7|Sharks and Shorelines – Teacher Guide Performance Expectations: Middle School MS-LS2-1. Analyze and interpret data to provide evidence for the effects of resource availability on organisms and populations of organisms in an ecosystem. MS-LS2-2. Construct an explanation that predicts patterns of interactions among organisms across multiple ecosystems. MS-LS2-4. Construct an argument supported by empirical evidence that changes to physical or biological components of an ecosystem affect populations. Vocabulary: Bathymetry: the study of underwater depth of bodies of water. The word bathymetric relates to measurements of the depths of oceans or lakes. Sea surface temperature: is the water temperature close to the ocean’s surface. This temperature can be measured remotely by satellites. 8|Sharks and Shorelines – Teacher Guide Suggested flow for Part 2: 1. Distribute copies of the student worksheet for Part 2 to students. The teacher answer key is on the next page. 2. Project the http://www.ocearch.org/ website and walk students through some of the basic functionality. 3. It may be useful to give students a background on some of the geographic features of the sea floor to give them some context for where the sharks go. If students can make connections between these features it will help them to understand how scientists use location clues as a starting point for asking more questions and conducting research. The tracked sharks tend to stay on the continental shelf of the United States. So it’s a little unusual to see a shark venture far out into the deeper waters beyond the continental shelf. 4. Use the websites below to show students what the ocean floor looks like and give them context for understanding the difference between the continental shelf and the deep ocean. a. Use the link below to project the bathymetric map of the Atlantic Ocean floor created by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). URL: http://www.nnvl.noaa.gov/MediaDetail.php?MediaID=572&MediaTypeID=1 Talking points for this image: Notice how the continental shelf of the East Coast gently drops off The Mid-Atlantic ridge is the world’s longest mountain range that splits the Atlantic Ocean into East and West. The Puerto Rico Trench is the deepest part of the Atlantic b. Use the link below to show an animated tour of the sea floor created by using a combination of ship-based measurements and satellite data. Go to the link and click play on the video, which was created by the Environmental Visualization Laboratory at NOAA. URL: http://www.nnvl.noaa.gov/MediaDetail2.php?MediaID=662&MediaTypeID=3&Resource ID=104527 c. Click this link to view a collection of materials by NOAA on the ocean floor, including background information on the tectonic plates, trenches, canyons, volcanoes, and more: URL: http://www.education.noaa.gov/Ocean_and_Coasts/Ocean_Floor_Features.html 5. After this introduction, send students to computers to work through the tasks on their worksheet and move about the room to support them as questions arise. 6. When students have completed the worksheet, regroup and have a class discussion. Since students could track four different sharks, you may wish to have students who researched the same shark combine together to compare their description of their shark’s movement. Alternatively, you could group students together who researched different sharks so that they can compare and contrast the difference in shark movement. 9|Sharks and Shorelines – Teacher Guide SHARKS AND SHORELINES Student Worksheet – TEACHER ANSWER KEY Part 2: Track a Shark! Instructions: Go to http://www.ocearch.org/ and explore the site for a few minutes to understand how it works. After you have explored, in the left hand box under sharks, enter the names: Mary Lee, Betsy, Genie, and Katharine. Type the full name, hit enter, then type another name. If you try to select the name as it pops up below, it may be difficult to select more than one shark at a time. Once you have all four sharks selected, under tracking activity, select “last two years.” Under gender and stage of life leave it as the default “all”. Under tagged at, select “Cape Cod”. Then click “track shark.” For easier map viewing, close the social media box on the right side, and then your map should look approximately like the image to the right. When you mouse over one of the circles on the colored line, it indicates the time and date of the shark’s ping as shown in the image below on the left. If you click on a dot, you get the time and date AND the name of the shark. The large orange circles with the white center show the most recent location of the shark. When you click on the orange circle, you get detailed information about the shark (example in the image below on the right). OCEARCH™ Screenshot 10 | S h a r k s a n d S h o r e l i n e s – T e a c h e r G u i d e OCEARCH™ Screenshot OCEARCH™ Screenshot Answer the questions below utilizing the OCEARCH™ website with the tracks for Mary Lee, Betsy, Genie, and Katharine displayed. Questions: 1. What is a ping? Can sharks send a ping when they are underwater? (hint: mouse over the information “i” in the Global Shark Tracker box. Answer: A ping is when the shark’s dorsal fin breaks the surface of the water and transmits a signal to a satellite overhead. The satellite then transmits an estimated geo-location that is placed on the map. Sharks do not send a ping when they are underwater. 2. Some sharks have large gaps in tracking data, what might account for this? (hint: look at recent pings for a clue) Answer: If sharks don’t surface long enough for the location to be detected, there might a gap in the tracking data. The next time the shark surfaces, we will know where it is but we will not be able to tell where it went between pings. 3. Based on the map you have generated of the sharks’ movement over 2 years, what is one thing that all 4 sharks have in common at first glance? Answer: For the most part, all sharks stay in the Atlantic Ocean right off of the East Coast of the United States. Most of the pings don’t go farther north than Massachusetts and don’t go farther south than Florida. 4. What are some differences that you notice? Refer to sharks by name when describing the differences. Answer: In February and March 2013, Mary Lee went much farther out into the ocean than the other sharks. In December 2013, Betsy went the farthest out into the Atlantic Ocean and then the next ping wasn’t until April 2014 when she showed up in the Gulf of Mexico. Only Betsy and Katharine went into the Gulf of Mexico, but Betsy ventured the farthest into the Gulf, while Katharine stayed closer to Florida. 5. How can you tell which direction sharks are moving? Answer: Start by mousing over the dots to look at the dates. Then see which dates come first. For example, you can tell if a shark is moving south if the newer dates are all south of the first dot you examined. 6. Which island was Mary Lee near during February 2013? Answer: Bermuda 7. Zoom in on Cape Cod. In which months does it appear that Mary Lee, Betsy, Genie, and Katharine sharks are near Cape Cod? Answer: In general, it seems that they are there from August through December. 8. If the line between two dots (pings) goes across land, what can you infer about a shark’s path? Answer: Since sharks can’t move across land, it just means that the shark likely swam around a land feature but didn’t surface long enough to ping. So the map drew a line to connect the dots, but that’s not really accurate. Or if the shark did surface long enough, maybe there was a fault with the transmitter. 11 | S h a r k s a n d S h o r e l i n e s – T e a c h e r G u i d e Now that scientists have access to shark tracking data, they are just beginning to get a picture of where sharks spend their time. However, there is still much research to be done before scientists know why sharks where go where they do. Betsy, Genie, Katharine, and Mary Lee are all the same species of shark – great white. Pick one of these sharks to track. **Note for teacher: Genie and Betsy do not have as many pings, so if you have students that may need more time for activities need other modifications you might suggest that they choose one of these two sharks. Once you have decided on the shark, delete the other three sharks from the map by clicking on the “x” next to their names in the Global Shark Tracker box. Which shark will you track?_______answer key includes all 4 sharks___ Use the map on page 10 (page 19 of the teacher guide) of this worksheet to help you take notes about shark location. It may be useful to change the tracking activity time parameters, for example, you could track one year or just one week. By fine tuning your shark track, you might be able to get an idea of how long it stays in one location. At the very bottom of the map, you can click full screen to get rid of the control box for better viewing. When you locate your shark, pay attention and make note of the underwater geographic features nearby on the map. Note that the darker the blue color, the deeper the water. The light blue areas are shallower waters and are usually located above a continental shelf. You can also see mid-ocean ridges and trenches on the OCEARCH™ map. The image below shows a 3-D version of the sea floor. Image Credit: NOAA Environmental Visualization Lab 12 | S h a r k s a n d S h o r e l i n e s – T e a c h e r G u i d e Use the hints and guiding questions below to help you get started with your research. The goal of your research is to establish a profile for your shark, which will serve as a starting point for trying to answer the question “why does my shark go where it goes?” 9. Under tracking activity select “past year” and then click track shark. Write a detailed description of what your shark did in the last year. Where does your shark go during the summer, fall, winter, and spring? Use cities, states, directions (N, S, E, and W), and geographic features in your answer. Use the map on page 10 (page 19 of the teacher guide) to write location notes to help you craft your answer. **Teacher note: the answers to the following questions will vary since the data is real-time. If you use this lesson a year from when it was written, the shark track could be very different from the answers below. These example answers for Mary Lee and Katharine are based off of tracking data from the years 2014-2015. Answers: Mary Lee: Mary Lee spent some of Jan 2014 out in the deeper water off of the continental shelf, then for most of 2014 she stayed fairly close to the East Coast between the cities of Charleston, SC and Jacksonville, FL. In Dec 2014 she headed NE, nearly in the same direction as she was in Jan 2014, but this time not go past the edge of the continental shelf. In Jan 2015 she pinged back in the area where she spent most of 2014 and was directly off the coast from Savannah, GA. Katharine: She pinged near Daytona Beach, FL in Jan 2014 and then headed north in Feb 2014. She swam around the area between Savannah, GA and Jacksonville, FL during the next few months. From May to June 2014 she went south around the tip of Florida, stopping at Key West on May 27th and then into the Gulf of Mexico. Between July 6th and July 17th she swam out of the Gulf and around the tip of Florida but didn’t ping between those dates. She then started heading north and was already to Daytona Beach by Jul 21, 2014. She was off the coast of NC in September 2014 and headed toward Cape Cod in Oct, Nov, and part of Dec 2014. In December 2014 she started to head away from the cape and by Jan 2, 2015 she was at the edge of the continental shelf west of NYC. By Jan 5, 2015 she was still off the continental shelf but had reached due east of Delaware. There were some weird pings that showed up on Jan 10th on land, but that was probably some kind of transmission error. Either way, she pinged several times on the 10th and she was very close to the Cape Hatteras National Sea Shore in NC. She continued moving south down the coast and on Jan 22, 2015 she pinged off of the coast of SC near Hilton Head Island. Genie: In Jan 2014 Genie was near the coast by Savannah, GA and then she swam south toward Jacksonville, FL by the end of Jan. She pinged again in April 2014 off the continental shelf SE of Virginia Beach, VA. By May she had moved north, still off the continental shelf but this time east of the NJ coast. On May 25, 2014 she pinged off the coast of the Eastern Shore of VA and then headed south where she pinged again on July 21, 2014 near Savannah, GA. By Sept 2014 she was headed back north and pinged off of the coast of VA again. The next time she pinged she was near Cape Cod in Oct 2014. 13 | S h a r k s a n d S h o r e l i n e s – T e a c h e r G u i d e Betsy: On April 18, 2014 Betsy was far out in the Gulf of Mexico directly south of Louisiana. Then on April 23, 2014 she pinged closer to FL near Cape Coral. She stayed in this area until at least the beginning of June. Her next ping wasn’t until Sep 27, 2014 off the island of Nantucket. She pinged near Nantucket a month later on Oct 22, 2014 and then headed directly south and pinged again near the continental shelf east of NJ on Nov 15, 2014. She headed south and then pinged right near Rehoboth Beach on the Delaware coast on Nov 21, 2014. Her last ping was the same day but she had headed out to sea and was due east of DE off the continental shelf. 10. Select “all activity” under tracking activity and then click track shark. If your shark took a surprising or unusual path, where did it go? Answers: Mary Lee: Mary Lee has a lot of history and a lot of pings. In all of her activity dating back to her tag date of Sept 17, 2012 – the most unusual event was when she went headed due east from Long Island, NY in Jan 2013 and then went north a little bit near the edge of the continental shelf and then headed south and pinged at Bermuda in late Feb 2013. She then headed SW of Bermuda and didn’t start heading back to the US coast until March 2013. She pinged near the coast of NC in late March 2013. Katharine: Katherine went into the Gulf of Mexico and spent a lot of time there just due south of Panama City, FL in June 2014. She also seems to surface a lot compared to the other sharks. She has a lot of pings! But from July 21-28 she has no pings and swims really far NE from Daytona Beach, FL in a northerly direction and pings again far off the coast of Charleston, SC. Genie: Genie’s path was pretty consistent. She traveled north and south off the coast of GA and up to Cape Cod. The only real anomaly was when she was farther out in the ocean due east from Cape Hatteras in April 2014. Betsy: Went far out into the Gulf of Mexico in April 2014. She also went very far out in the Atlantic past the continental shelf in Dec 2013. 11. Make a list of reasons that sharks might go to certain places (think about the things that every animal needs to do). Answer: Sharks need to find a mate and breed They need to give birth to young They need food 14 | S h a r k s a n d S h o r e l i n e s – T e a c h e r G u i d e 12. The article “Shark Spring Break: Florida Swarm Explained” (link below) says that sharks head south for spring break. Did your shark spend the spring near Florida? URL: http://news.discovery.com/animals/sharks/shark-spring-break-swarm-explained130308.htm Answers: Mary Lee: in the last two years (2013-2014) Mary Lee did not swim to FL during the spring months Katharine: Was near the coasts of Georgia and Florida in the spring of 2014. Genie: In the spring of 2014 Genie was nowhere near Florida. In April 2014 she was off the coast of Virginia and North Carolina, far out in the water past the continental shelf. Betsy: Did head south for Spring Break and spent April 2014 in the Gulf of Mexico. 13. One thing that all 4 sharks had in common was they were originally tagged on Cape Cod in Massachusetts. Why do the sharks come to the Cape Cod area? A scientist recently tweeted this clue; can it help you answer the question? “A weird concentration of black spots has been spotted in a satellite image. Where is this, what are the black spots? #beachmystery #sharkbait https://goo.gl/maps/2bTHA” Open the map and see if you can identify where the black dots are (circled in red below), what they are, and explain why they are important to sharks. Google Maps Screenshot Answer: The black dots are gray seals on the beach near the Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge on Cape Cod. Gray seals are food for the sharks and are a huge reason for the sharks return to this area. **Teacher note: If students can’t figure out the relevance of the image, they could read this article about sharks returning to Cape Cod to eat gray seals. URL: http://www.slate.com/articles/health_and_science/science/2013/07/sharks_return_to_cape_cod _gray_seals_are_the_bait.html 15 | S h a r k s a n d S h o r e l i n e s – T e a c h e r G u i d e In the image to the right, the green dots represent 649 verified white shark observations in the Northwest Atlantic Ocean from 1800-2010. The white shark observation records that were used to make this graphic were compiled from a variety of sources including commercial fishery observer programs, scientific research surveys, commercial and recreational fisherman, newspaper articles, recreational tournaments, scientists, landings data (total number of species captures, brought to shore, and sold), and more. Image credit: Tobey Curtis, NOAA Fisheries Unfortunately, because the sightings only occur when human-shark interactions happen, this does not capture the whole picture of shark movement, however, this data set from a 2014 paper by Tobey Curtis et al. represents the most comprehensive information on great white shark location in the Northwest Atlantic Ocean so far. Continued shark observation and tagging data will only help to complete the picture and will be useful for shark conservation and management moving forward. 14. Describe the location of the Northwest Atlantic Ocean (see above image) shark observations with respect to the coastlines, continental shelf, and the deep ocean. Answer: In general, the observed sharks were in shallower waters on the continental shelf and close to the coastline. In rare occasions they have been spotted out in deeper waters. 15. Is it possible that sharks could occur in deeper waters past the continental shelf? Answer: Yes, because these data are limited to human-shark interactions, it is possible that we don’t know the whole story. There are a few sharks in the OCEARCH™ data and even in the image above that went farther out into the Atlantic (Bermuda). In fact, there are OCEARCH™ tagged sharks around the rest of the world that don’t always stay near coastlines. **Teacher note: you may want to point students to the whole OCEARCH™ map since this activity restricted them to sharks that were tagged at Cape Cod and live in the Atlantic. This will help them see the behaviors of sharks that live in other parts of the world. 16. How can satellite tracking data help to give a better picture of shark movement compared to human observation alone? Answer: Sharks must have some interaction with humans in order to be captured and tagged, but after that the satellite picks up shark location when sharks surface. This location data doesn’t depend on human-shark interaction. This is drastically different from human observation alone, which might consist of only one location data point for one shark. The satellite tracking data helps to depict the whole journey of a single shark over several years, which is a far richer data set. In addition, when sharks are tagged, shark details like age and gender are recorded so researchers can combine this information with the track to start to help answer questions like “do female great white sharks have different migration patterns than male sharks?” 16 | S h a r k s a n d S h o r e l i n e s – T e a c h e r G u i d e Image credit: CC by Tobey Curtis et al. (2014), NOAA Fisheries In the images above, shark sightings by season are overlaid on maps of sea surface temperature (SST). As shown in the key, the redder the color of the ocean, the hotter the SST. The darker blue ocean color indicates cooler SST. In the diagram, CC stands for Cape Cod; NYB = New York Bight; CH = Cape Hatteras; FL = Florida; GOM = Gulf of Mexico; and CS = Caribbean Sea. 17. Based on the information in the sea surface temperature (SST) images above, make a statement that describes how shark location relates to SST. Be sure to use approximate locations and temperature values in your description. Answer: In the winter months when SST is cooler near Cape Cod, sharks were spotted off the coast of North Carolina and all the way down to Florida where it is warmer than approximately 20o C. In the summer months when SST rises significantly to around 35o C around Florida and all the way up to Delaware, the majority of shark sightings were around the NE coast from Delaware and north to Canada where the water is much cooler than approximately 30o C. In the fall and spring when SST is less extreme, the sharks were more evenly distributed along the coast compared to winter and summer. In the spring, there were a few more in around Florida than in the fall, but this is likely because the some sharks were still hanging around after the winter months. In the fall, there were a few more sightings in the NE, likely because not all of the sharks had started their southward migration for winter. 17 | S h a r k s a n d S h o r e l i n e s – T e a c h e r G u i d e 18. Based on your findings so far, describe what you think are some of the major influencers of shark movement. Answer: Sharks appear to prefer swimming in waters near the coast and on the continental shelf. It also appears that they move where food is and they are influenced by sea surface temperature. 19. What are some unanswered questions you have at this point? These unanswered questions could form the basis of a scientific research project. Answers may vary but could include: Why do some sharks go way out into the deep ocean – like the one that showed up near Bermuda? Where do the sharks go to breed and have young? How will climate change influence shark movement? How does the population of gray seals affect the shark population? 20. Sharks are pretty fierce animals, but they are not immune to threats. What kinds of things or activities might endanger sharks? Answer: Commercial fishing, finning. 21. Looking at the track of your shark, where are areas that you think the shark could potentially encounter humans? Mark them on your paper map on page 10 with the letter “x”. Answer: Will vary, but students should mark areas where their shark came very close to the coast where humans might be swimming, surfing, or doing other recreational activities. 22. How does have shark tagging data help us to conserve sharks and shark habitat? Answer: If we can see where sharks go, we can determine which areas might need more protection. For example, shark nursery areas might need to be protected. To ensure that sharks can reproduce and keep their populations going strong. 18 | S h a r k s a n d S h o r e l i n e s – T e a c h e r G u i d e 19 | S h a r k s a n d S h o r e l i n e s – T e a c h e r G u i d e Other Resources for Part 2: For more information on the tracking of Great White Sharks: http://www.wired.com/2013/12/secret-lives-great-white-sharks/ Article on where in the world you are most at risk for a shark attack: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/northamerica/usa/10953652/Shark-attackwhere-in-the-world-are-you-most-at-risk.html Other tracking sites: Analyzing Ocean Tracks – Designed for classroom use, this site includes several investigations using real data collected from marine animals, buoys, and satellites. http://oceantracks.org/ Tagging of Pelagic Predators (TOPP) – This website shows animal tracks, including historic tracks and real-time tracks from a wide variety of marine predators. http://www.gtopp.org/ Expedition WhiteShark – An app for iPad/iPod that includes shark tracking, shark bios, and a gallery. http://www.expeditionwhiteshark.com/ R.J. Dunlap Marine Conservation Program – Track sharks with Google Earth. http://rjd.miami.edu/education/virtual-learning/tracking-sharks Virtual Expedition (by R.J. Dunlap Marine Conservation Program) – Includes more in depth videos on how tagging is done and explains the equipment used in the tagging process. http://rjd.miami.edu/virtual-expeditions/ 20 | T e a c h e r G u i d e – S h a r k s a n d S h o r e l i n e s Part 3: Predator and Prey – A Game of Survival in a Marine Ecosystem Grades: 6-10 Subject: Science Purpose: This game provides a kinesthetic way for students to experience the effects of predation on marine organisms. The game is conducted outside on school grounds. Students will play the roles of predator and prey and over several iterations of the game; they will learn how the predator and prey populations are interconnected. Time: Two to three 45-minute class periods (1 class period to discuss trophic levels and predation, 1 class period to play the game, 1 class period for data analysis and discussion) Materials: 20 red, 8 blue, and 2 white bandanas or strips of fabric (for 30 students) Approximately 200 red poker chips and 100 blue poker chips (for 30 students) Pieces of paper for each student that play a ray or a small fish Approximately 20 crayons of different colors attached to string Graph paper Objectives: The student will… Define and describe different trophic levels in a marine ecosystem. Compare and contrast the roles of predator and prey in a marine ecosystem. Describe how the population size at one trophic level can influence the population size of another trophic level. Examine the role of an apex predator in a marine ecosystem. Graph and analyze the change in populations over multiple generations. Next Generation Science Standards: Disciplinary Core Ideas: LS2A Interdependent Relationships in Ecosystems LS2B Cycle of Matter and Energy Transfer in Ecosystems LS2C Ecosystem Dynamics, Functioning, and Resilience LS4D Biodiversity and Humans Crosscutting Concepts: Patterns Cause and Effect Energy and Matter Stability and Change 21 | T e a c h e r G u i d e – S h a r k s a n d S h o r e l i n e s Science and Engineering Practices: Analyzing and Interpreting Data Using mathematics and computational thinking Constructing explanations Engaging in an argument from evidence Performance Expectations: Middle School MS-LS2-1. Analyze and interpret data to provide evidence for the effects of resource availability on organisms and populations of organisms in an ecosystem. MS-LS2-2. Construct an explanation that predicts patterns of interactions among organisms across multiple ecosystems. MS-LS2-4. Construct an argument supported by empirical evidence that changes to physical or biological components of an ecosystem affect populations. Vocabulary: Apex predator: a top-level predator with no natural predator of its own; a shark is an example. Consumer: an organism that gets energy by eating other organisms. Consumers are also known as heterotrophs. Phytoplankton: are small and microscopic, photosynthesizing organisms that are found drifting in water and include cyanobacteria, diatoms, and dinoflagellates. Predator: an animal that preys on or eats others. Prey: an animal that is hunted and killed by another animal for food. Producer: an organism that make its own energy by converting light or chemical energy into organic matter; plants are producers. Producers are also known as autotrophs. Zooplankton: are small and microscopic swimming animals that live in water; zooplankton are often the larval stage of larger organisms like crab. 22 | T e a c h e r G u i d e – S h a r k s a n d S h o r e l i n e s Suggested Flow: 1. Do a preliminary assessment with your students (do now, entry task, etc.) to elicit their prior knowledge about food chains and trophic levels. At the beginning of class, have students draw a food chain in their notebooks. They can use any organism that comes to mind. Their food chains should include a producer, a primary consumer, a secondary consumer, and a tertiary consumer. Based on this preliminary check for understanding, you may need to teach or reteach the basics about trophic levels. Have students identify which of the organisms in their food chain would be considered predators and prey. Ask them if something can be both a predator and prey and if so, have them identify that organism in their food chain. An example: Eagle (tertiary consumer or carnivore) Snake (secondary consumer or carnivore) Mouse (primary consumer or herbivore) Plant (producer) 2. To prepare for the game, begin with the steps below. Teacher Preparation: a) There are three different organisms in the game: lemon shark, spotted eagle ray, and small fish. The ratio is 1 shark: 4 rays: 10 small fish. If you have 30 students, you can have double the numbers to 2 sharks: 8 rays: 20 small fish. Make other adjustments as needed. b) Obtain the appropriate number of bandanas or colored strips of fabric for each organism. Sharks are white, rays are blue, and fish are red. c) Prior to the game, you will need to hang the crayons around the area of your school grounds in which you wish to play this game. Be sure to spread them out. Make some locations obvious and hide others. You can vary the number of crayons based on the number of students, but you should at least have 20 multi-colored crayons. You may also need to vary the number of crayons based on the size of the space in which you are playing – the bigger the space and more spread out the crayons are, the harder it is for students to find the crayons and survive the game. If you are playing in a large space, you will want to add additional crayons. The crayons represent food and where the crayons are located is the equivalent of a feeding station. The reason behind using multiple colors is so students can’t go to a feeding station and make several marks with one crayon. d) Be sure to map out clear boundaries for the playing field so you can communicate this to the students. Establish a location for the trading station where you or a student will hand out chips in return for crayon marks. 23 | T e a c h e r G u i d e – S h a r k s a n d S h o r e l i n e s 3. Quick overview of the game: At the start of the game, you will give the small fish a 10 second head start to begin looking for crayons, then let rays go, and then wait 10 more seconds before releasing the shark(s). Each round should last about 8 minutes and represents one year. The small fish start with 5 red chips. Their goal is to collect crayon marks at the feeding stations. When they get 6 different colored crayon marks on a paper, they can exchange those for 1 red chip at the trading station. Then they head out and collect more marks, repeating this process. During this time they must try to avoid predators (sharks and rays) that will be tagging them and taking their red chips. Small fish must finish the game with 1 red chip in order to survive. Spotted eagle rays start with 5 blue chips. Their goal is to collect red chips from the small fish AND different colored crayon marks from the feeding stations. When they have they have 3 red chips and 3 different colored crayon marks, they may trade these for 1 blue chip at the trading station. Then they head out and collect more marks and/or red chips. During this time, they will also be avoiding sharks who will try to tag them and take their blue chips. Rays must finish the game with 1 blue chip in order to survive. Sharks start with no chips, but will move around trying to tag small fish and take a red chip from them (only one at a time) or they will tag rays and take a blue chip from them. Even though rays are collecting red chips from the small fish, sharks cannot take the red chips from the rays. The red chips that the rays have represent the ray food only. In order to survive, sharks must end the game with a total of 12 red and/or blue chips. Predators cannot tag an animal when they are already being tagged and predators can only take one chip at a time from the prey. Predators CAN attack prey when they are at feeding stations. Students playing predators may even discover the strategy of waiting for prey near feeding stations. Play at least 3 rounds. You can assign different organisms to each student in a new round. This will give them a different experience and it won’t be as easy for them to find crayons since they will have to adjust to their new organism’s strategies and feeding stations. At the end of a round, blow a whistle or use some kind of signaling device that you have agreed upon with the students. Record survivor data and then play another round. Repeat this for several rounds. Indoor Preparation with Students: 4. Project or share the flow chart diagram on the next page to summarize the goals for each organism. Make sure all students understand their goals before they head outside. The chips are the equivalent of “lives” or “health” (for the sharks, they will represent food since sharks don’t need to capture crayon marks). 24 | T e a c h e r G u i d e – S h a r k s a n d S h o r e l i n e s Lemon Shark Credit: Albert Kok CC by 3.0 Spotted Eagle Ray Small Forage Fish Credit: NOAA Credit: John Norton CC by 2.0 Shark (1 student) White bandana on arm Starts with no chips Rays (4 students) Blue bandana on arm Starts with 5 blue chips Piece of paper Small Fish (10 students) Red bandana on arm Starts with 5 red chips Piece of paper Goal: Find rays and small fish and take 1 chip at a time from them. Cannot tag ray or fish while they are being tagged by another predator. Sharks can only take blue chips from rays (not the red chips that rays are collecting for food). Collect as many chips as you can by tagging rays and fish. You must finish with at least 12 red/blue chips to survive. Goal: Find small fish and take a red chip from them by tagging them. Find crayons and mark paper once for each crayon found. Can trade 3 red chips plus 3 different colored crayon marks for a 1 blue chip at the station. Collect as many new chips as you can. Avoid sharks while looking for crayons. If you run out of chips, you must sit out for the remainder of the game. You must finish the game with at least 1 blue chip to survive. Goal: Find crayons and mark paper once for each crayon found. Can trade 6 different colored marks for 1 red chip at the station. Collect as many new chips as you can. Avoid predators while looking for crayons. If you run out of chips, you must sit out for the remainder of the game. You must finish the game with at least 1 red chip to survive. 25 | T e a c h e r G u i d e – S h a r k s a n d S h o r e l i n e s 5. Before heading outside, reinforce the following game rules: No pushing. No arguing. If a predator finds prey, the prey must give up their chip. While this exchange is happening, the prey can’t be tagged by another predator. You can be tagged by a predator while you are eating (getting a crayon mark). 6. Give students their appropriate bandana or fabric strip and the starting number of chips for each organism. The head outside with students and follow the instructions below. Outside Instructions: a) Show students the boundaries and the area you have established as the trading station where they can trade sheets with crayon marks for new chips. b) Remind students of their roles and goals. c) At the start of the game, give the small fish a 10 second head start to begin looking for crayons, then let rays go and wait 10 more seconds before releasing the shark(s). d) Each round should last about 8 minutes. Play at least three rounds. Feel free to assign different organisms to each student in a new round. That way they get a different experience and it won’t be as easy for them to find crayons since they will have to adjust to their new organism’s strategies and feeding stations. e) At the end of a round, blow a whistle or use some kind of signaling device that you have agreed upon with the students. f) Use the data table on the next page to record the numbers of animals that have survived. Begin another round and then record data. Complete as many rounds as you can. 26 | T e a c h e r G u i d e – S h a r k s a n d S h o r e l i n e s Number of Surviving Organisms Starting # Round 1 Small Fish (must finish with 1 red chip to survive) Spotted Eagle Ray (must finish with 1 blue chip to survive) Lemon Shark (must finish with 12 red and/or blue chips to survive) 27 | T e a c h e r G u i d e – S h a r k s a n d S h o r e l i n e s Round 2 Round 3 Round 4 Round 5 7. Try the variations below for a round or two, or make up your own variation to show students how populations are affected when the apex predator is removed or when the primary consumer population shrinks. a) Shark population suffers because of finning - remove or reduce the number of lemon sharks b) Massive overfishing in the Atlantic - reduce the population size of small fish 8. Be sure that all students collect their chips and bandanas and head back inside for data analysis and discussion. 9. You can have students graph the data collected during the game or create a class bar graph with sticky notes on a board to use for discussion. 10. Talking points for final discussion are below. You could also have students write up a conclusion based on these discussion and their graphs. Discuss the changes in population from round to round (year to year). Have students speculate on the trends that they see in the graph. Ask students who played both prey and predators if there were specific strategies that they used during the game in order to hide from prey or attack prey. Ask students if they think that their techniques were representative of what actually happens in nature. The food chain in this game included a small forage fish, a ray, and a shark. Have students determine the trophic levels for each of these organisms. Forage fish eat phytoplankton and zooplankton, so they would be considered both primary and secondary consumers. Sharks eat a wide variety of prey, but are considered the apex predator in a marine ecosystem. Rays eat crabs, bivalves, shrimp, squid and other organisms in addition to fish. But for the purposes of this game, they are either a secondary or tertiary consumer. In Part 1 of this lesson plan, students learned about the intimidation behavior of the lemon sharks. The mere presence of the sharks swimming through an area prevented marine herbivores from eating the sea grasses and mangrove seedlings, which in turn allowed the mangrove forests to flourish and provide habitat for all organisms to thrive. Discuss the concept of intimidation behavior with students and ask them to describe what, if any, intimidation strategies the predators in this game might have used. 28 | T e a c h e r G u i d e – S h a r k s a n d S h o r e l i n e s Bibliography: Curtis, Tobey H., Camilla T. McCandless, John K. Carlson, Gregory B. Skomal, Nancy E. Kohler, Lisa J. Natanson, George H. Burgess, John J. Hoey, and Harold L. Pratt, Jr. "Seasonal Distribution and Historic Trends in Abundance of White Sharks, Carcharodon Carcharias, in the Western North Atlantic Ocean." PLOS One. PLOS One, 11 June 2014. Web. 27 Jan. 2015. <http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0099240>. Dawicki, Shelley. "Study of White Sharks in the Northwest Atlantic Offers Optimistic Outlook for Recovery." NEFSC: Science Spotlight, NOAA Fisheries Service. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 11 June 2014. Web. 22 Jan. 2015. <http://www.nefsc.noaa.gov/press_release/pr2014/scispot/ss1405/>. Holland, Jennifer S. "Blue Waters of the Bahamas." - National Geographic Magazine. National Geographic Society, Mar. 2007. Web. 03 Dec. 2014. <http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2007/03/bahamian-sharks/holland-text>. Standards: National Governors Association Center for Best Practices & Council of Chief State School Officers. Common Core State Standards. Washington, DC: Authors, 2010. NGSS Lead States. Next Generation Science Standards: For States, By States. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2013. 29 | T e a c h e r G u i d e – S h a r k s a n d S h o r e l i n e s SHARKS AND SHORELINES Student Worksheet Part 1: Lemon Sharks and Mangroves Section A: Video Viewing Guide Watch the Sharks and Shorelines | EARTH A New Wild video (3:56 min) and answer the questions below. URL: https://vimeo.com/116273821 © Janet Haas for The Nature Conservancy 1. In the video, scientists are shown tagging different ocean predators. What kinds of data can scientists collect from the tags? 2. How does the tagging help with conservation? 3. What have researchers learned about lemon sharks through tagging? 1|Student Worksheet – Sharks and Shorelines – Part 1 4. What does the mangrove ecosystem provide for organisms? 5. How do sharks maintain the mangrove ecosystem? 6. List some examples of marine herbivores. 7. How do the sharks help humans? Optional: Your teacher may assign you to check out the “Ecosystem Explorer,” which was inspired by the EARTH A New Wild series and includes a “Shark World” where you can explore the shark ecosystem through interactive, multi-media content. You can find the interactive content here: http://www.pbslearningmedia.org/resource/5aeed659-7f0b-417f-81d9-5f2e9c747644/ecosystemexplorer-earth-a-new-wild/ 2|Student Worksheet – Sharks and Shorelines – Part 1 SHARKS AND SHORELINES Student Worksheet Part 2: Track a Shark! Instructions: Go to http://www.ocearch.org/ and explore the site to understand how it works. After you have explored, in the left hand box under sharks, enter the names: Mary Lee, Betsy, Genie, and Katharine. Type the full name, hit enter, then type another name. If you try to select the name as it pops up below, it may be difficult to select more than one shark at a time. Once you have all four sharks selected, under tracking activity, select “last two years.” Under gender and stage of life leave it as the default “all”. Under tagged at, select “Cape Cod”. Then click “track shark.” For easier map viewing, close the social media box on the right side, and then your map should look approximately like the image to the right. When you mouse over one of the circles on the colored line, it indicates the time and date of the shark’s ping as shown in the image below on the left. If you click on a dot, you get the time and date AND the name of the shark. The large orange circles with the white center show the most recent location of the shark. When you click on the orange circle, you get detailed information about the shark (example in the image below on the right). OCEARCH™ Screenshot 1 |S t u d e n t W o r k s h e e t – S h a r k s a n d S h o r e l i n e s – P a r t 2 OCEARCH™ Screenshot OCEARCH™ Screenshot Answer the questions below utilizing the OCEARCH™ website with the tracks for Mary Lee, Betsy, Genie, and Katharine displayed. Questions: 1. What is a ping? Can sharks send a ping when they are underwater? (Hint: mouse over the information “i” in the Global Shark Tracker box.) 2. Some sharks have large gaps in tracking data, what might account for this? (hint: look at recent pings for a clue) 3. Based on the map you have generated of the sharks’ movement over 2 years, what is one thing that all 4 sharks have in common at first glance? 4. What are some differences that you notice? Refer to sharks by name when describing the differences. 2 |S t u d e n t W o r k s h e e t – S h a r k s a n d S h o r e l i n e s – P a r t 2 5. How can you tell which direction sharks are moving? 6. Which island was Mary Lee near during February 2013? 7. Zoom in on Cape Cod. In which months does it appear that Mary Lee, Betsy, Genie, and Katharine sharks are near Cape Cod? 8. If the line between two dots (pings) goes across land, what can you infer about a shark’s path? 3 |S t u d e n t W o r k s h e e t – S h a r k s a n d S h o r e l i n e s – P a r t 2 Now that scientists have access to shark tracking data, they are just beginning to get a picture of where sharks spend their time. However, there is still much research to be done before scientists know why sharks go where they do. Betsy, Genie, Katharine, and Mary Lee are all the same species of shark – great white. Pick one of these sharks to track. Once you have decided on the shark, delete the other three sharks from the map by clicking on the “x” next to their names in the Global Shark Tracker box. Which shark will you track?_______________________________________________________ Use the map on page 10 of this worksheet to help you take notes about shark location. It may be useful to change the tracking activity time parameters, for example, you could track one year or just one week. By fine tuning your shark track, you might be able to get an idea of how long it stays in one location. At the very bottom of the map, you can click full screen to get rid of the control box for better viewing. When you locate your shark, pay attention and make note of the underwater geographic features nearby on the map. Note that the darker the blue color, the deeper the water. The light blue areas are shallower waters and are usually located above a continental shelf. You can also see mid-ocean ridges and trenches on the OCEARCH™ map. The image below shows a 3-D version of the sea floor. Image Credit: NOAA Environmental Visualization Lab 4 |S t u d e n t W o r k s h e e t – S h a r k s a n d S h o r e l i n e s – P a r t 2 Use the hints and guiding questions below to help you get started with your research. The goal of your research is to establish a profile for your shark, which will serve as a starting point for trying to answer the question “why does my shark go where it goes?” 9. Under tracking activity select “past year” and then click track shark. Write a detailed description of what your shark did in the last year. Where does your shark go during the summer, fall, winter, and spring? Use cities, states, directions (N, S, E, and W), and geographic features in your answer. Use the map on page 10 to write location notes to help you craft your answer. 10. Select “all activity” under tracking activity and then click track shark. If your shark took a surprising or unusual path, where did it go? 11. Make a list of reasons that sharks might go to certain places (think about the things that every animal needs to do). 5 |S t u d e n t W o r k s h e e t – S h a r k s a n d S h o r e l i n e s – P a r t 2 12. The article “Shark Spring Break: Florida Swarm Explained” (link below) says that sharks head south for spring break. Did your shark spend the spring near Florida? URL: http://news.discovery.com/animals/sharks/shark-spring-break-swarm-explained130308.htm 13. One thing that all 4 sharks had in common was they were originally tagged on Cape Cod in Massachusetts. Why do the sharks come to the Cape Cod area? A scientist recently tweeted this clue; can it help you answer the question? “A weird concentration of black spots has been spotted in a satellite image. Where is this, what are the black spots? #beachmystery #sharkbait https://goo.gl/maps/2bTHA” Open the map and see if you can identify where the black dots (circled in red) are, what they are, and explain why they are important to sharks. Google Maps Screenshot 6 |S t u d e n t W o r k s h e e t – S h a r k s a n d S h o r e l i n e s – P a r t 2 In the image to the right, the green dots represent 649 verified white shark observations in the Northwest Atlantic Ocean from 18002010. The white shark observation records that were used to make this graphic were compiled from a variety of sources including commercial fishery observer programs, scientific research surveys, commercial and recreational Image credit: Tobey Curtis, NOAA Fisheries fisherman, newspaper articles, recreational tournaments, scientists, landings data (total number of species captures, brought to shore, and sold), and more. Unfortunately, because the sightings only occur when human-shark interactions happen, this does not capture the whole picture of shark movement, however, this data set from a 2014 paper by Tobey Curtis et al., represents the most comprehensive information on great white shark location in the Northwest Atlantic Ocean so far. Continued shark observation and tagging data will only help to complete the picture and will be useful for shark conservation and management moving forward. 14. Describe the location of the Northwest Atlantic Ocean (see above image) shark observations with respect to the coastlines, continental shelf, and the deep ocean. 15. Is it possible that sharks could occur in deeper waters past the continental shelf? 16. How can satellite tracking data help to give a better picture of shark movement compared to human observation alone? 7 |S t u d e n t W o r k s h e e t – S h a r k s a n d S h o r e l i n e s – P a r t 2 Image credit: Tobey Curtis et al. (2014), NOAA Fisheries In the images above, shark sightings by season are overlaid on maps of sea surface temperature (SST). As shown in the key, the redder the color of the ocean, the hotter the SST. The darker blue ocean color indicates cooler SST. In the diagram, CC stands for Cape Cod; NYB = New York Bight; CH = Cape Hatteras; FL = Florida; GOM = Gulf of Mexico; and CS = Caribbean Sea. 17. Based on the information in the sea surface temperature (SST) images above, make a statement that describes how shark location relates to SST. Be sure to use approximate locations and temperature values in your description. 8 |S t u d e n t W o r k s h e e t – S h a r k s a n d S h o r e l i n e s – P a r t 2 18. Based on your findings so far, describe what you think are some of the major influencers of shark movement? 19. What are some unanswered questions you have at this point? These unanswered questions could form the basis of a scientific research project. 20. Sharks are pretty fierce animals, but they are not immune to threats. What kinds of things or activities might endanger sharks? 21. Looking at the track of your shark, where are areas that you think the shark could potentially encounter humans? Mark them on your paper map on page 10 with the letter “x”. 22. How does shark tagging data help us to conserve sharks and shark habitat? 9 |S t u d e n t W o r k s h e e t – S h a r k s a n d S h o r e l i n e s – P a r t 2 10 |S t u d e n t W o r k s h e e t – S h a r k s a n d S h o r e l i n e s – P a r t 2