Iceman

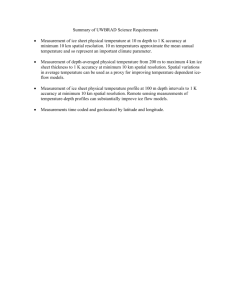

advertisement

STAR-BULLETIN & ADVERTISER (Honolulu, Hawaii) Nov. 15, 1992, pp. D1+ (c) 1992, The Washington Post Reprinted with permission 'ICEMAN' GIVES LOOK AT 5,000 YEARS AGO by Boyce Rensberger The Washington Post INNSBRUCK, Austria--They call him the man in the ice. As scientists have come to realize since his frozen body emerged from a glacier in the Italian Alps last year, he is the nearest we may ever come to meeting a real person from the Stone Age. The "Iceman," who scientists now know lived about 5,300 years ago, had been in the ice 1,000 years when the Egyptians built the pyramids at Giza, more than 3,000 years when Jesus was born. Yet he was found with a remarkable array of clothing, weapons and equipment, including some mysterious objects of types never seen before. Some--including the man's fur hat, the oldest known in Europe--were found just last summer in a new expedition to the normally icebound site on the Austrian-Italian border. Archaeologists are excited, because the man's body was found not in a grave, the usual source of ancient remains, but at a campsite he made during a sojourn in the mountains, and because snow and ice covered him and his things, preserving them almost perfectly. His perishable belongings--items made of wood, leather, grass, and apparently even food and medicines--have come out of the ice virtually intact, providing scientists with the most intimate picture ever seen of the daily life of a prehistoric man. For example, his ax, which has a copper head, looks and feels as new and dangerous as on the fall day in about 3300 B.C., when the man leaned it against a rock before bedding down for his last night. It is among the oldest copper axes known and one of the best made, dating from the dawn of the use of metals. Archaeologists know that fateful night was in the autumn, because frozen with him was a ripe blackthorn fruit, the plumlike berry also called sloe, which grows at lower altitudes and ripens in the fall. The man's body is startlingly well preserved--by far the most lifelike from prehistoric times--and is being kept in a highsecurity freezer at the University of Innsbruck medical school. The body was naturally freeze-dried and is in such good condition that pores in the skin look normal. Even his eyeballs can still be seen behind lids frozen open, and CT scans show the brain and other internal organs in place. "This is a fantastic find," said Konrad Spindler, a University of Innsbruck archaeologist who is a leader of the international group studying the discovery. Coming to life "It is the first time we have a man coming from life, not from the grave. We have his complete equipment, including the organic materials. It should be possible to get a picture of a time in prehistory we never saw until now." "We have never had a prehistoric discovery as complete as this," said Andreas Lippert, a University of Vienna archaeologist who led the expedition to the site last summer. The group found more than 400 objects, most of them parts of the man's clothing. Yet several key questions remain. What was he doing so high in the mountains? How did he die? And, most intriguing to archaeologists, did he come from one of the known prehistoric cultures of the region, or does he represent something entirely new? What is clear is that he lived during one of the more critical transitions in the development of human culture, when stone tools were beginning to give way to metal. "We see many great changes in culture at this time--the beginning of the plow and of the wheel," Spindler said. "And now, from the man's ax, we see a wonderful refinement in metallurgy." Farming Farming, which began in the Middle East about 5,000 years earlier, had spread to much of Eurasia by 5,300 years ago. The man probably came from a village of farmers who raised wheat, barley and oats and herded sheep, goats and cattle. The man in the ice was discovered Sept. 19, 1991, by Helmut and Erika Simon, a German couple hiking in the Alps. Near the 10,500-foot-high ridge that defines the Austrian-Italian border they were tramping over the snow and ice of a commonly used pass when they saw a human head and shoulders sticking out of the ice. The body was lying face down, its skin a tawny color and the head hairless. The Simons reported it to police in the Italian state of South Tirol. Border problems The local Carabinieri, Italian police familiar with the common problem of retrieving bodies of modern climbers, insisted that this time the site was in Austria and not their problem. Two days later the Austrian police from north Tirol arrived with a helicopter and--not realizing the site's importance--used an air hammer to hack the body out of the ice. They accidentally cut into the man's hip, but his legs stayed stuck. Forensic officials spotted the copper-bladed ax on a nearby rock and, presuming foul play in the man's death, took it as "evidence." Bad weather forced a temporary retreat. But word of the find encouraged curious hikers to trek to the body, and several tried to chop it free with ski poles and walking sticks. On Sept. 23, four days after the find, a forensic team from the University of Innsbruck helicoptered to the site, found that meltwater had refrozen around the body and began again to chop. When they pulled out the prone body, it was later realized, the man's penis remained embedded in the ice, torn off in the recovery. The workers also gathered up some pieces of fur and leather clothing, bits of string, a leather bag and a flint dagger. A long stick that appeared to be a bow was still partly embedded in ice, so workers broke off the free part and took that too. The undertaker Then the body was flown to a nearby undertaker, placed in a coffin, taken to the university's department of forensic medicine and, late that day, laid out on an autopsy table. "I was notified the next morning," Spindler said, "and went to see it. We stood around the body on the table. I saw the stone tools and the copper ax and said: `I think it could be 4,000 years old.' Nobody believed me." Hikers and skiers had been lost in the Alps many times, but they usually emerged a few decades later when the flow of the glaciers transported them to lower altitudes where they melted out. Moreover, these "young" bodies were usually horribly transformed by the ice, their flesh turned into misshapen blobs of "fat wax." This man in the ice, though dried and somewhat shriveled like a mummy, looked too good to be very old. Dating solved A team of glaciologists from Innsbruck soon resolved the question with another visit to the site. They found that the body had lain at the bottom of a narrow ravine. Snow could have filled the 6-to-10-foot-deep crevice, but the resulting ice could not flow out of it. The glacier must have moved a few feet above the man's head, leaving him exactly where he lay. His quiver The glaciologists also found evidence to support the man's antiquity--his quiver, which contained 14 arrows, two of them fitted with flint arrowheads, hardly the choice of any bowman who lived since the Iron Age swept Eurasia more than 3,000 years ago. And the glaciologists explained why the body had only just emerged. Earlier in 1991 great storms had blown dust from North Africa into the Alps, darkening the snow cover. The dust absorbed solar heat, causing more than the usual amount of snow to melt during the summer of 1991, exposing the body. Body's age When the age of the body became evident (radiocarbon dating of a bit of flesh from the hip wound would confirm it to be 5,300 years old), Italian authorities began to insist it was found on their side of the border after all. Given the mountainous terrain, it was not immediately clear where the border lay. "Someday, maybe, we will have to give the mummy to South Tirol," Spindler said. "But now I do not see how he can be moved. He must be conserved under very strict conditions." *** ICEMAN (See picture, "Iceman.") Clad in his deerskin tunic and a cape made of rushes, the Iceman, as some call him, faced the rigors of the Alpine wilds with his first-aid kit--two chunks of tree fungus with natural antibiotic properties dangling on leather thongs. This reconstruction, by Washington Post staff artist Johnstone Quinan, is based on evidence obtained by archaeologists. But, because the man's garments were badly fragmented, the cuts of clothing shown are conjectural. Except for the canister, artifacts shown are reproduced from photographs. The Quiver was made of a single piece of leather folded in half with the bottom sewn shut and the vertical edges stitched into a groove in a length of hazel wood that served as a reinforcing spine. Of 14 arrows made of viburnum wood, only two (tip of one shown here) were finished with heads, notches and feathers. The heads and feathers were glued with birch gum and lashed with fine sinew. Had the ice not preserved the wooden handle, the flint blade of this dagger would have been considered an arrowhead. Surprisingly small, it probably served not as a weapon but as a hand tool, perhaps for cutting leather. The backpack frame consisted of an arch made of hazel wood and two slats of larch. There are notches on each piece indicating that they were lashed together. The frame may have been inside a leather pack or lashed to it, as depicted. In addition to the cape made of grass or rushes and the piecework deerskin tunic, the man may have worn trousers or leggings. Some said they saw "something" on the man's legs before he was removed from the ice but it may have been part of the tunic. Shaped like a fat pencil, this may have been his tool for resharpening flint blades. At the point is a hard material embedded in the wooden handle that may have been pressed against the edge of arrowheads to detach flakes. The only clue to the man's emergence from the Stone Age is this copper-bladed ax. The handle of yew ends in a natural "knee" into which a deep notch was cut. The blade was inserted, then lashed with wet leather, which shrunk. A leather pouch, which may have been part of a belt, contained two flint scrapers, a gouging tool, a bone needle and a mass of black fibers that may have been tinder. A hank of light rope or cordage was made from grass spun into a thickness of about 1/8". It may be about six feet long, but rather than undo the coil to measure, archaeologists will make a replica to see how long the cord is. Two canisters of birch were found near the body. They stand about eight inches tall and seven inches wide and were made by rolling the bark into a tube and stitching it to flat pieces for the bottom.