Chapter Six * How to Get a Grip on Scientific Style

advertisement

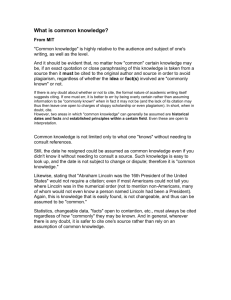

Chapter Six – Getting a Grip on Scientific Style 1 Chapter Six – How to Get a Grip on Scientific Style I know – you’d think I’d have covered “scientific style” earlier in the book. But remember the constant reminder throughout this whole book to keep your reader in mind when making writing decisions? This is why I saved this until the end. When you start a book with this kind of stuff, readers get bored really quickly. Frankly, I don’t blame them; I’d get bored, too. In fact, when I read books about writing and presenting, I ignore all the “how to” rules until I need them, which isn’t until I actually have to write or present something. Then, I look them up as I need. I am going to assume you’re pretty similar. I am also taking a somewhat different approach even in this chapter on the so-called rules of writing. It’s important to me that you have an idea of why style in science is different. The rules are reflections of the culture of science, of what scientists do when writing that show their participation in scientific culture. Many scientific writers may not be aware of these cultural rules – most of us are not aware of why we participate in the conventions that we do or the history behind how those traditions got started. This is sort of a defining feature of any culture – it’s learned outside of our conscious awareness or control. However, because writing in the sciences is not something most of us grew up with, we need to learn many of the rules just like we had to learn the Pythagorean Theorem or a sonnet’s rhyme scheme. Scientific Culture Every family, group, organization, country has a culture – patterns governing interaction that has arisen over time. Using the patterns means you are a cultural insider. Further, using the patterns form the foundation of success since they are what cultural participants are expecting. I’m going to highlight just a few of the elements that seem more relevant to writing and the writing rules associated with them. The Cultural Prime Directive – Science is about the science itself I believe this is the strongest cultural tradition of science and the one with the most influence on the writing and speaking styles associated with scientific communication. In the history of science, the key development was the “scientific method” itself. The scientific method at its core is a process for discovery that relies on observation, thinking, investigation (tests of some sort), and more thinking. Before the scientific method, knowledge often developed according to authoritative decree rather than evidence. Prior to the evolution of science (and “science” as a method has historically many more practitioners than the western ones we are taught in school), events were explained by stories, such as the Greek Myths, that caught the emotion and description of a happening, but weren’t particularly good at explaining what was going on in a way that could then be used to explain similar events or distinguish between dis-similar events. The scientific method (see Wikipedia for a fascinating and short history of this!) became a means of more reliably grouping together similar things and distinguishing dis-similar things which gave human beings a much more consistent understanding of events in the world. Also, though it may not seem so now, since the scientific method is a method – a process for discovery – then presumably anyone who can think and follow the method can practice science. Now, as in all things, there are people better at science than others, just as there are better singers, better athletes, and better poets. But the idea that there is a way of exploring the world through systematic discovery remains extremely powerful. Extending the argument a bit further, if the main contribution of science is a process for systematic discovery that anyone willing to accept the method can perform, then science also needs a way of overseeing itself. This is where the notion of replicability comes in. Though anyone can Chapter Six – Getting a Grip on Scientific Style 2 participate in the scientific method, no one person can decree they’ve discovered truth. Instead, other people must agree, usually using their own observations, tests, and thinking. Thus, consensus must be reached before an understanding of something achieves any high status. In this way, no one person can rule their field. (On the other hand, consensus can be problematic, too, when it blocks acceptance of a new idea at the cost of overturning a highly accepted theory -- see Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolution for a philosophical look at the progression of knowledge in science.) They must participate in the whole enterprise, with the oversight of other practitioners. Okay, reality check: do scientists always work this democratically? No, not really. But no culture ever works according to its own description. It’s interpreted by the people in that culture. But the ethic of consensus in science has also remained powerful over time. So, there are two cultural notions in the world of science that have remained powerful over time and have a tremendous influence of the way science is communicated: 1) the scientific method as a process for systematic discovery; 2) the ethic of consensus. How do these influence writing styles? Let’s take a look at a few absolute rules. Rule #1: Use only the grammatical third person -- Do not use the second person in primary scientific publication. o Throughout this book, I’ve used the second person “you” to Are people really metaphorically speak directly to the reader, as though I am secondary to engaging you in a personal conversation. This is absolutely information? No. But this is a cultural ideal taboo in scientific report or review writing. If science and thus plays a role in knowledge is achieved by consensus, then my particular shaping scientific thoughts or your particular thoughts are not directly discourse. Science cannot happen without relevant (this may be why so many people are put off when scientists, and they they first begin reading in the scientific literature!). Instead, make their way into the writer and reader are secondary to the information itself. process via in-text Do not speak directly to the reader by using the second citations where credit for intellectual work is person. given. Citations are o Strategy: There is one main way to get around the how the writer temptation to use the second person – make the topic of acknowledges the what you are saying the subject of what you are saying. For contribution of humans to the scientific process. example, I could revise the previous sentence as follows: “First, make the topic of the sentence – what the sentence is about – the grammatical subject of the sentence.” Instead of “When you put a rat in a maze with food…”, write “When rats are put in a maze with food, …”. Or, write “Upon entering, the etched glass windows splinter the sunlight” rather than “When you first walk in, you immediately notice how the etched glass windows splinter the sunlight.” Rule #2: Use the passive as often as necessary. o Okay, I’m going to go out on a limb here and offend some otherwise entirely wonderful writing instructors by saying unequivocally that the whole “avoid using the passive” obsession is downright silly. Consider the following pair of sentences: The dog chased the cat The cat was chased by the dog. In the first sentence, who or what is the sentence about? It is about the dog. In the second sentence, the same question reveals the sentence is about the cat. The “aboutness” of sentences is known as the discourse topic. Discourse, as a level of grammatical structure, is very important to information management Chapter Six – Getting a Grip on Scientific Style o o 3 during speech. Virtually every language on the planet has some grammatical means of playing with what the sentence is about. In English, our default mode is that the grammatical subject is also the discourse topic. In other words, the subject of the sentence (the grammatical subject) is what the sentence is about (the discourse topic). This is linguistically convenient, but quite confusing when it comes to explaining the importance of passive sentences. Instead of avoiding the passive, use the passive correctly, as necessary. In fact, most of the time, if you don’t think about it, you’ll use it correctly because it is a grammatical structure that was acquired during childhood along with the rest of language. Strategy: If science is about the science itself, then the use of first person in writing is potentially quite intrusive. First person can be used sparingly in the Introduction and in the Discussion, especially at the ends of each section, but should not be used elsewhere. The reader knows who did the testing, so endlessly repeating “I designed the survey, we handed out the survey, I calculated the statistics, we collated the answers” is unnecessary. Also, note the grammatical subject of the sentence is “I” – meaning, as you just learned above – that the sentence is about whoever “I” is rather than about the information being conveyed. I realize that for some, removing the first person (and even second person) feels depersonalizing. I view it as a grammatical challenge – it takes serious creativity to write complex prose without resorting to first and second person. The two best structures for accomplishing this are to (1) make the topic the subject of the sentence; 2) use passive as much as necessary. Note: for those of you wondering why I’ve chosen to use 1st and 2nd person, I’ll say simply that teaching texts are different from scientific texts. When teaching, a more conversational tone succeeds better than the 3rd person stance common to scholarly prose. No culture is complete without rules for behavior, dress, etc. Can you show up to a job interview in a business suit and flip flops? Not if you want to get the job. How do you know this? Cultures provide rules for interaction as well as meanings for interaction. Science is no exception. I think of “writing styles” such as APA, CSE, etc. as behavioral codes belonging to science culture. I don’t have to like to code to know that I have to follow it. Each writing style enforces visual and lexical uniformity in its publications, making them instantly recognizable to members of the group. The ultimate guide to APA style is the APA style guide, now in its 5th edition. It’s a thick book covering just about every question regarding formatting a paper that a writer might encounter. Given the advent of the Internet, though, not even the APA can publish changes fast enough, so they provide additional formatting help at APA Style, http://apastyle.apa.org/. Not all the rules are provided here, just the most recent changes. If you need all the rules – or most that you can think of – I’d recommend the site Research and Documentation Online, featuring Diana Hacker – http://www.dianahacker.com/resdoc/. A variety of drop down menus and sample papers provide you with virtually everything you need in terms of formatting. Also, a quick web search for “APA style” will bring up a zillion possible other sites to mine for instructions. Chapter Six – Getting a Grip on Scientific Style 4 For those who’d rather not fill their heads with the specifications regarding commas, periods, and parentheses or fill their computer screens with multiple open windows, you can try what I use (and many, many of my students): a web-based references manager. These are powerful software programs (RefWorks, Citation Manager, End Note, etc.) that provide storage and organization for all your references, automatically format reference sections, and even format papers correctly by providing downloadable utilities. These programs are quite expensive, though. Check to see if your school or college provides a subscription to one of these services. If you’re not sure, ask a librarian. Alternately, there are some terrific, very inexpensive on-line programs that can help. One such program is Noodle Bib at http://www.noodletools.com/. This service also provides links to many other tips and tools that help with writing. Currently, the price is only $8.00 a year for an individual. One advantage to Noodle Bib is that it helps the beginning science writer understand publication types themselves. Another, solely for generating individual references, is sponsored by the Landmark project and called the Son of Citation Machine: http://citationmachine.net/. This service is free and also provides some of the learning features of Noodle Bib, though does not have note-taking and other tools. As you may have gathered by this point, I am not going to review the rules of formatting and citation. There are so many excellent sources available to you that I’d prefer to use space explaining things that are frequently left out. A few common sense pointers are to double space unless your instructor says not to; include a title and title page unless your instructor says not to; use page numbers throughout the paper; and find out how your instructor prefers multiple pages to be bound. Some like staples, some like folders, and some like binder clips. n. The mother of all networks. First incarnated Understanding Scientific Publication Platforms/Technologies This is an area that is not so common sensical. I think my generation (40-something) actually have an easier time understanding the impact of technology on publication because we grew up through the information revolution. The college I went to didn’t get its first computer lab until my sophomore year and I didn’t begin using the Internet regularly for research until the late 1990s. Now, like you, getting me away from my computer-as-portal-to-theworld takes all but a constitutional amendment. The downside to the extraordinarily easy access to information is serious confusion about what the Internet is and the credibility of the information found there. In terms of the latter, review what was said in Chapters 1 & 2 about using scholarly search engines and evaluating transparency in order to get to scholarly information. The first problem I’ll take up next. What is the Internet? I am not a technology expert, so let me strongly urge you to do a quick search at dictionary.reference.com and read for yourself. These two paragraphs from Jargon File are a good introduction. beginning in 1969 as the ARPANET, a U.S. Department of Defense research testbed. Though it has been widely believed that the goal was to develop a network architecture for military command-and-control that could survive disruptions up to and including nuclear war, this is a myth; in fact, ARPANET was conceived from the start as a way to get most economical use out of then-scarce large-computer resources. As originally imagined, ARPANET's major use would have been to support what is now called remote login and more sophisticated forms of distributed computing, but the infant technology of electronic mail quickly grew to dominate actual usage. Universities, research labs and defense contractors early discovered the Internet's potential as a medium of communication between _humans_ and linked up in steadily increasing numbers, connecting together a quirky mix of academics, techies, hippies, SF fans, hackers, and anarchists. The roots of this lexicon lie in those early years. (Internet. (n.d.). Jargon File 4.2.0. Retrieved February 20, 2008, from Dictionary.comwebsite: http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/Internet) Chapter Six – Getting a Grip on Scientific Style 5 Basically, the Internet is a collection of smaller networks resulting in a huge conglomeration of connections that provide virtually instant access to all kinds of information. For publication, what this means is that the Internet is “simply” another technology that makes print available to the reader. Paper is another kind of technology. Each technology has advantages and disadvantages. The Internet doesn’t kill trees but is still difficult to transport (at least until world wide wireless is perfected). Paper is portable, but degrades and has to be stored under climate controlled conditions. From the standpoint of making scholarly information available to readers, it’s important to understand that “e-based” sources are simply sources being made available in an electronic form. The electronic form has two main versions: html and pdf. Hyper Text Mark Up (html) language is usually easier to read, navigate, and store but is somewhat less authoritative. Portable Document Format (.pdf) is a kind of image file; sort of like a picture taken of the printed page that is published electronically. Because the .pdf file looks exactly like the original, it is considered more authoritative and should be the version used for citing page numbers. Being an image file, it takes up more storage “space”. But both versions provide the same information and both are legitimate electronic forms for publication. .html version of article – easy to read on computer because it doesn’t have columns .pdf version of the same article – this is how it looks in print. Another “disadvantage” of the Internet is how difficult it is to manage what gets put where. In print, scholarly publications are published in journals, the individual issues of which are annually bound. Then, they are stored in a physical location with others of its kind. Thus, in the “olden days”, learning about research was multi-sensory in that you had to walk into a real building, navigate its interior and physically extract the object from a shelf. While laborious, one learned about publication types because references were in one area, research journals in another, lay print (newspapers, magazines) in another, and fiction on a different floor entirely. The brain formed a mental concept map that associated physical movement with visual reinforcement of information types altogether in a lovely, intellectuallynurturing bubble. Such is not the case with the Internet. There is nothing about an electronic or digital connection which in and of itself forces one kind of information to be in one place and another kind some place else. Thus born were the search engine, the database, and an interface joining the two. Using search engines though is less intuitive than going into a library and finding the reference section. In fact, for most people, there is nothing whatsoever that feels “natural” about their first trip into the Chapter Six – Getting a Grip on Scientific Style 6 scholarly literature. Search engines are language-based and the language used in science comes from a culture that beginning researchers are just entering. I don’t have a ready solution for this! But I have found that the net savvy modern reference librarian is among the most useful human beings on the planet. One who can teach what s/he knows (not the same thing as having the ability) ought to be revered along with saints. I am quite good at finding sources, but am still struggling to convey how I know what I know about searching to students. Since my background is linguistics – and my theoretical specialty was the interaction of meaning and structure – I am good at using language-based devices, but this isn’t always helpful. I think this is the main disadvantage of the Internet. It’s a well-known one, too, otherwise there’d not be the proliferation of helpful services there are. For example, EBSCO Host, one of the larger service providers, has an excellent left side bar featuring search terms and journals related to the words input by the searcher. This makes it much easier to figure out how a particular discipline talks about itself and gives the searcher the power to narrow or expand searches with a single click. Effective searching takes understanding and organization. Remember how we dissected a citation back in Chapter 1? Understanding a citation also teaches you about publication and information types. The title is the name of the article written by the researchers. The article is then published in a journal, a kind of scholarly magazine dedicated to a particular field of science. Journals often belong to publishing houses which then make articles available to the public. Publishers make articles available in print and electronically. When in print, articles appear in something like a magazine, in single issues which are bound annually. When electronic, articles are made in available in .html or .pdf forms. Electronic versions of articles are made available through publisher’s website. Readers may access articles by going directly to the journal’s website as happens when searching from a library’s catalog. Or, articles can be accessed through host services. Host services contract with many different publishers to make access to electronic copy easier. Host services provide the search engine to help users navigate the particular databases they’ve aggregated. Hosted databases are usually arranged topically, by discipline or research area. This allows researchers to access many articles from many different individual journals at the same time. Thus, in the citation, the whole publishing process is represented. Over the next several years, I imagine that wireless capabilities and technologies will become increasingly seamless and allow for most anything available in print to be available electronically, evolving to the point where relatively fewer items will be available in print. There are some challenges with this idea, the main one being that computers are difficult to read on. I’ve not met a student yet who liked reading on the computer screen. The experience really tires out the eyes and the one-pageat-a-time layout makes comparative reading from different portions of the same text next to impossible, despite the existence of “thumbnails” (those tiny little pictures used to “show” you what’s on another page). Reading between multiple articles at once is also very difficult on a computer screen and this is a skill most researchers must develop to succeed. On the other hand, computers’ functionally allow for much easier note-taking and storage! So, each technology has its advantages and disadvantages. Citing Sources Style Guide You must cite sources when you write scientifically. In the beginning, you will cite more than will be the case if you remain in a research career. Undergraduates must cite more often than graduate students; grad students cite more than practitioners. There are two reasons for this. First, as your knowledge of a field progresses, so does your understanding of what is considered “common knowledge.” At first, you must provide citations for this information because it is new to you – the citations are proof of the Chapter Six – Getting a Grip on Scientific Style 7 Host service Search terms The database Title, authors, journal – the complete citation! Left side bar with terms Publisher Name of journal html version – also called full text Send to self Export the citation to a bibliographic manager .pdf version – use for citing page #s intellectual effort you’ve put in while acknowledging the sources of what you’ve learned. As a graduate student, you figure out more of what is common knowledge, and may cite somewhat less. Second, using citations is part of writing ethically. It is assumed given scientific culture and the ethic of consensus that if you are participating, you will give credit to those ideas that come from other people as a means by which the reader can identify specifically which ideas come from you. Chapter Six – Getting a Grip on Scientific Style 8 Stylistically, there are a few different citation situations students frequently have questions about or get wrong their first time out. Let’s go over these now. Put citations where they make sense As McMillan (2006) points out, citations should be placed logically in the sentence where they will best indicate who did or said what. For example, in the sentence “The computer culture of young children has been studied in terms of education and play (blah, xxxx; blah, xxxx)”, which researcher studied which facet? Did they both investigate both conditions or did one examine education and one examine play? It is more accurate to write “The computer culture of young children has been studied in terms of education (blah, xxxx) and play (blah, xxxx)”. The second sentence is more accurate and clear. Only cite what you have read Frequently, you will come across useful information attributed to another researcher in a paper you are reading – who do you cite? Since citations are a record of what you have actually read, you only cite the papers that you have read yourself. You have two choices at this point. Find the article that is referred to and read it yourself or use a “pointing” strategy to keep the citation clear and honest. For example, if Johnson is the author of the paper you read and Everett the author of the paper cited in the paper you read, then the citation needs to point to Everett in some way. Here are a couple of possibilities: “According to Everett (in Johnson, 2007, 137), blah blah blah)” or “Blah, Blah, Blah (Everett, in Johnson, 2007, 137)”. In both cases, explicit mention is made of the fact that you are referring to Johnson’s representation of Everett rather than Everett’s original paper. If you are referring to a quote that you then want to quote, then follow the pattern above, but specify the nature of the quotation: “Johnson (2007) quotes Everett as writing “‘blah blah blah’” (137)”. Note that there are single quotes within the double quotes. Quoting is discouraged in scientific writing Another curious cultural ideal in the science writing world is the covert belief that language is just another tool to be used for the scientific enterprise. If there were a more efficient, clear, precise communicative process at our disposal, we’d use it, but since language is all we have, words are what we use. Thus, in the sciences in general, quotes are used sparingly. In fact, avoid quoting except for very specific rhetorical purposes: quote when you very much want to argue for something or against something. These are the cases where the exact language of the original source is important. The use of original language because you cannot figure out how to paraphrase it and the author/s said it so well is not an acceptable reason to quote. If you cannot imagine a paraphrase, you have 2 jobs to do. First, you must find simpler sources – often secondary ones – and study the idea again until you better understand it. Second, you must synthesize sources so that you are not relying so much on a single paper to get an idea across. Synthesizing Sources – the CYA strategy for ethical writing in the sciences This topic was covered earlier in the book, but could use more explanation here. One of the best guides to understanding ethical writing and avoiding plagiarism is Miguel Roiq’s Avoiding plagiarism, self-plagiarism, and other questionable writing practices: A guide to ethical writing at http://facpub.stjohns.edu/%7Eroigm/plagiarism/. Currently, Dr. Roiq makes his work freely available as either an .html document or a word document that can be saved (if used for a class, please write and ask Dr. Roiq’s permission). In brief, Rioq points out a paradox in science writing that is notoriously difficult to address: Chapter Six – Getting a Grip on Scientific Style Writers cannot plagiarize Writers must paraphrase Technical language has no synonyms 9 Quoting is discouraged What is a writer to do? The answer is SYNTHESIZE SOURCES. When you discuss the literature on a topic, you have the responsibility to read more than a single source for your information. Gone are the days of Wikipedia and Encyclopedia Britannica. You must actively integrate your sources. Why? You stand a lesser chance of committing unintentional plagiarism if you use more than main source for your work. If 4 people have basically said the same thing, then when you say it – and cite all 4 sources – you are “proving” the publication history behind the idea and the reader is more confident that you know what you are talking about. Multiple citations are most common when providing definitions and explanations of a topic. Cite after first mention Unlike other traditions, in science, cite immediately after the first sentence from a source, even if the next few sentences will be from the same source. Remember, to the reader of science, each and every sentence should have intellectual history attached to it. If there is no citation at the end of the sentence, the assumption is that the idea belongs to the writer (you are the beginning of the intellectual history of the idea). Every sentence—every idea – belonging to another source should include a citation. If after the first citation, the following sentence obviously belongs to the same source because there is a clear, logical connection (chronological, process, test-result, etc), then you do not have to cite again. If an entire paragraph is from a single source, cite after the first sentence, somewhere in the middle, and at the end, so it is utterly clear where the information comes from. Generally, you should not be writing whole paragraphs from a single source, but if you are explaining the history of an idea or a particular methodology, then it may happen. Only include page numbers for quotes or very specific information Generally speaking, the only time in APA style that you need to provide a page number is if you are quoting directly. Sometimes, though, you might reference a piece of very specific information – a result or particular claim, for instance – in which case it is a courtesy to provide the reader with the page number so they can find it for themselves quickly. Every writing culture that you learn feels weird at first. Science is no different. Poets write in iambic pentameter, but talk over cups of coffee in regular conversations. When you write in iambic pentameter, you participate in the culture of the poet, however briefly. Scientists write according to the conventions of scientific writing, in formats that have evolved over many generations of discovery. When you write a research report, you participate in the culture of the discipline to which you have contributed, and become part of the long history that is science.