Sustainability News – 3 July 2015

advertisement

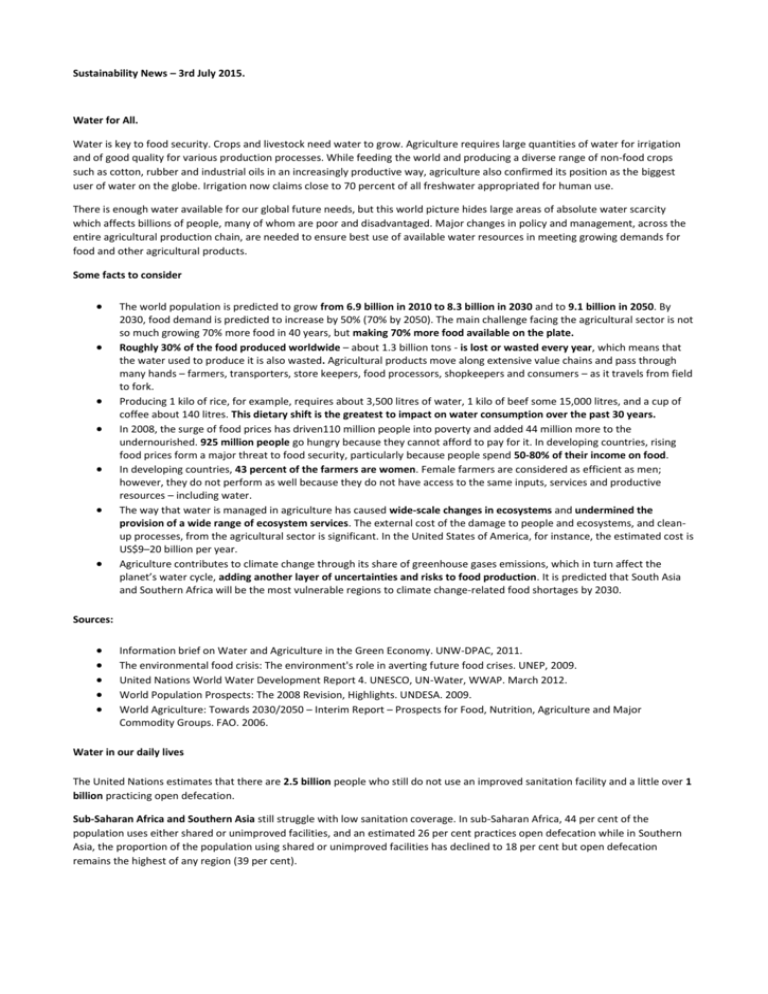

Sustainability News – 3rd July 2015. Water for All. Water is key to food security. Crops and livestock need water to grow. Agriculture requires large quantities of water for irrigation and of good quality for various production processes. While feeding the world and producing a diverse range of non-food crops such as cotton, rubber and industrial oils in an increasingly productive way, agriculture also confirmed its position as the biggest user of water on the globe. Irrigation now claims close to 70 percent of all freshwater appropriated for human use. There is enough water available for our global future needs, but this world picture hides large areas of absolute water scarcity which affects billions of people, many of whom are poor and disadvantaged. Major changes in policy and management, across the entire agricultural production chain, are needed to ensure best use of available water resources in meeting growing demands for food and other agricultural products. Some facts to consider The world population is predicted to grow from 6.9 billion in 2010 to 8.3 billion in 2030 and to 9.1 billion in 2050. By 2030, food demand is predicted to increase by 50% (70% by 2050). The main challenge facing the agricultural sector is not so much growing 70% more food in 40 years, but making 70% more food available on the plate. Roughly 30% of the food produced worldwide – about 1.3 billion tons - is lost or wasted every year, which means that the water used to produce it is also wasted. Agricultural products move along extensive value chains and pass through many hands – farmers, transporters, store keepers, food processors, shopkeepers and consumers – as it travels from field to fork. Producing 1 kilo of rice, for example, requires about 3,500 litres of water, 1 kilo of beef some 15,000 litres, and a cup of coffee about 140 litres. This dietary shift is the greatest to impact on water consumption over the past 30 years. In 2008, the surge of food prices has driven110 million people into poverty and added 44 million more to the undernourished. 925 million people go hungry because they cannot afford to pay for it. In developing countries, rising food prices form a major threat to food security, particularly because people spend 50-80% of their income on food. In developing countries, 43 percent of the farmers are women. Female farmers are considered as efficient as men; however, they do not perform as well because they do not have access to the same inputs, services and productive resources – including water. The way that water is managed in agriculture has caused wide-scale changes in ecosystems and undermined the provision of a wide range of ecosystem services. The external cost of the damage to people and ecosystems, and cleanup processes, from the agricultural sector is significant. In the United States of America, for instance, the estimated cost is US$9–20 billion per year. Agriculture contributes to climate change through its share of greenhouse gases emissions, which in turn affect the planet’s water cycle, adding another layer of uncertainties and risks to food production. It is predicted that South Asia and Southern Africa will be the most vulnerable regions to climate change-related food shortages by 2030. Sources: Information brief on Water and Agriculture in the Green Economy. UNW-DPAC, 2011. The environmental food crisis: The environment's role in averting future food crises. UNEP, 2009. United Nations World Water Development Report 4. UNESCO, UN-Water, WWAP. March 2012. World Population Prospects: The 2008 Revision, Highlights. UNDESA. 2009. World Agriculture: Towards 2030/2050 – Interim Report – Prospects for Food, Nutrition, Agriculture and Major Commodity Groups. FAO. 2006. Water in our daily lives The United Nations estimates that there are 2.5 billion people who still do not use an improved sanitation facility and a little over 1 billion practicing open defecation. Sub-Saharan Africa and Southern Asia still struggle with low sanitation coverage. In sub-Saharan Africa, 44 per cent of the population uses either shared or unimproved facilities, and an estimated 26 per cent practices open defecation while in Southern Asia, the proportion of the population using shared or unimproved facilities has declined to 18 per cent but open defecation remains the highest of any region (39 per cent). Did you know? 2.5 billion people – roughly 37 per cent of the world’s population – still lack what many of us take for granted: access to adequate sanitation. Open defecation is one of the main causes of diarrhea, which results in the deaths of more than 750,000 children under age 5 every year. Every 20 seconds a child dies as a result of poor sanitation. 80 per cent of diseases in developing countries are caused by unsafe water and poor sanitation, including inadequate sanitation facilities. Access to sanitation, the practice of good hygiene, and a safe water supply could save 1.5 million children a year. In 2006, the world’s population was almost equally divided between urban and rural dwellers. Nevertheless, more than 7 out of 10 people without improved sanitation were rural inhabitants. Doing nothing is costly. Every US $1 spent on sanitation brings a $5.50 return by keeping people healthy and productive Source: http://www.un.org/en/sustainablefuture/pdf/Rio+20_FS_Water.pdf Safe Water for all? Across Kenya, Uganda and Malawi, a small blue plastic box is helping millions to have longer, healthier and more productive lives. The simple yet ingenious innovation is a water purifying chlorine dispenser that is installed next to communal water sources. Designed by Innovations for Poverty Action and researchers at Harvard and UC Berkley, Dispensers for Safe Water is providing access to clean and safe water to over 2.6 million people, with dispensers at 10,000 water points. There is a strong need for this innovation. Almost 11% of the global population – 780 million people – are without safe drinking water, leaving them susceptible to harmful bacteria and waterborne diseases, such as cholera and diarrhea. Diarrheal disease is the second leading cause of death in children under five. Across all ages, it kills 1.8 million a year, and it is fifth for years of life lost due to premature mortality. The Dispensers for Safe Water project works to avoid these preventable illnesses through an inexpensive, sustainable program. The project, managed by Evidence Action, is simple yet highly effective. Water quality improvements at the household level are as effective as improving hygiene, sanitation or the water supply, but can be provided at a significantly lower cost. However, for these efforts to succeed, the household must be consistent and correct in how they treat the water, and avoid recontamination. This is why Dispensers for Safe Water is providing metered doses of chlorine – chlorine kills 99.99% of harmful bacteria and reduces the incidence of diarrhea by 40%. It purifies the water against recontamination for 24-72 hours, eliminating the risks from contact with unwashed containers or hands. Determining the best means of distribution was essential. In Kenya, providing chlorine packets in retail stores, even at the low cost of $0.30 per month, led to regular use in less than 10% of households. Instead, Dispensers for Safe Water eliminated user costs, recognizing that small fees raise little revenue while drastically reducing access. To further increase use, the dispensers are installed next to communal water sources, creating social pressure to conform and a constant reminder through the dispenser’s physical presence. A project’s sustainability requires more than simply providing the product. It must be integrated into and accepted by the community. To ensure this, approval is first obtained from the community leaders, and the program ensures community engagement by training key stakeholders and welcoming everyone to the installation. Local promoters encourage use and educate on the dangers of contaminated water, in addition to ensuring a consistent supply of chlorine. Altogether, the program has had sustained adoption rates between 42% and 80%. Dispensers for Safe Water is, according to Evidence Action, “one of the most cost-effective ways to reduce childhood diarrhea.” It costs less than $0.50 per person annually, and none of these costs are passed on to the communities. Beyond donations and grants, Evidence Action’s funding comes from carbon credit sales. By averting the use of firewood to boil water, they are reducing communities’ carbon footprints. Third party carbon project experts verify their programs and sell carbon credits. The profits are then reinvested towards the long term sustainability of the program. Recently, the project was the first to win Stage Three Funding with USAID’s extremely competitive Development Innovation Venture (DIV), for a grant of $5.5 million. This will enable Evidence Action to scale the project to 25 million people by 2018. Dispensers for Safe Water has extraordinary potential to provide a resource that should be available to all – clean, safe water. Sometimes the simplest ideas are the most significant. http://www.evidenceaction.org/#about A toilet with no water? Types of toilets in the developing world range from the traditional and incredibly insanitary pit latrines to more advanced flush toilets, depending on the area’s access to water, electricity, and sanitation services. While the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation rewards innovations in toilet research and design, here is a list of five innovative toilets that are actually in use in the developing world. 1. Earthworm Toilets. These toilets make the top of this list because of their unique use of both aerobic bacteria and earthworms that compost the human waste into limited-odor loam. An example of this in action in the developed world is in Quebec’s La Providence golf course. Fortunately for the developing world, a research project entitled “The Tiger Toilet” has been undertaken by the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and funded by a 2009 grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. This earthworm toilet would make use of tiger worms and would only have to be emptied every six months! 2. The Sulabh Toilet. The Sulabh toilet is a pan-trap squat toilet that uses a two-pit system minimizing both odor and water waste. Only one pit is ever in use at a time, and each pit can contain up to 3 years’ worth of waste. Sulabh was founded on the principle of liberating the Dalit caste in India from being forced into work as scavengers, and today has liberated more than 60,000 scavengers. A sustainable business network has accompanied Sulabh’s work, employing over 50,000 associates in 26 Indian states. 3. The Biofil Digester. Ghanaian Kweku Anno developed a simple, compact, on-site composting system that limits odor and avoids many of the problems of pit and ventilated pit latrines. The system itself uses a primary treatment of both aerobic bacteria and red worms to aerate the solid contents; the BioFil digester then treats what remains through a sand filter into a reed bed. Its installation is highly flexible as well, available to be installed beneath the ground, half-buried, or above ground. 4. The xRunner Toilet. The xRunner toilet is a waterless urine-diverting portable toilet that was developed by Noa Lerner, an Israeli industrial engineer. The toilet separates urine from feces and minimizes odor due to its enclosed and detachable pan. While Lerner initially focused on composting the waste in India, she soon found that the need was greatest in places without stable access to water because of drought. xRunner aims to equip 500 families in Lima this year with the dry toilets after a significant improvement was shown with 50 units. The system is unique because of its potential reliance on community entrepreneurs who can arrange weekly collection and processing of the contents of the detachable pans, similar to the PeePoo system used in Kenya and Pakistan today. 5. The EcoSan Toilet. This toilet is completely water-free and entirely closed; developed in the late 1990’s by Eco Sanitation Ltd, the EcoSan Toilet relies on dehydration of waste to limit odor and avoid the use of precious water resources. The excrement falls into a conveyer that rotates and moves the waste by mechanism every time the toilet lid is opened. This process dehydrates the excrement in approximately 25 days before it falls into a reusable collection bag. The waste, now 5-10% of its original mass, can be used for composting, fuel, or can be disposed of traditionally. The system itself also has a number of options including a toilet hut for privacy, different toilet bowls or urinals for other countries, or high-volume modifications. Some others http://cdn.intechopen.com/pdfs/33283/InTechSanitation_in_developing_countries_innovative_solutions_in_a_value_chain_framework.pdf http://sustainablog.org/2011/08/waterless-toilet/ http://www.gatesfoundation.org/What-We-Do/Global-Development/Water-Sanitation-and-Hygiene http://www.csmonitor.com/World/Global-Issues/2010/1119/World-Toilet-Day-Top-10-nations-lacking-toilets/Niger-12-million John Cambridge 3rd July, 2015.