Briefing_for_Protection_Cluster(April_2013)

advertisement

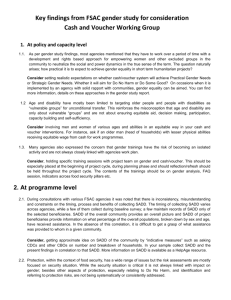

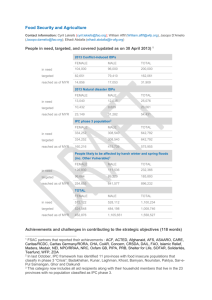

Briefing for Protection Cluster Key findings from FSAC gender study Policies and capacities 1. Protection implies implementing projects in impartial and non-discriminatory ways that promote the safety, dignity and integrity of the people receiving assistance. It also implies actively enquiring how (or if) protection risks related to gender in the Food Security sector are identified and mitigated; whether agencies’ interventions put the affected populations at a greater risk (Do No Harm); and how are protection mechanisms mainstreams in line with gender analysis in the project cycle. Since gender and protection are interlinked at various levels, and one affects the other, in the FSAC study on gender equality programming protection was also included. 2. Due to lack of conceptual understanding of theory and practice of protection on the ground, many agencies are already engaged in protection activities without being aware of it. However, these activities are often uncoordinated and not captured in project design. 3. In capacity mapping of 18 FSAC agencies, the following trends emerged: - - For effective gender equality programming, prior rapport with community is crucial. To set realistic goals in gender equality programmes, especially in the context of emergency where prior rapport with community is absent, important to take approaches such as Do No Harm and the Do Some Good. Do No Harm is being aware of gender inequality and trying to bring no further gender inequality by interventions and Do Some Good implies trying to create an atmosphere where different roles, positions and needs of women and men can be addressed 4 out of 18 FSAC agencies participating in this study have protection policy (Protection for Participating Populations, child protection and GBV policy). Almost 80% of the participating agencies reported to have staff code of conduct. Only 3 agencies reported to have received training on specific aspects of protection such as GBV and child protection but not on mainstreaming protection in food security. Only WFP has a protection policy (concentric model circle) that is relevant for identifying and addressing protection issues in food security interventions Most of the gender advisors play a twin role with gender and protection being the most natural combination of skills. WFP has a protection policy which is based on a concentric model. In the inner circle of the concentric circle, protection problems directly related to hunger are housed, in the middle circle protection issues related to food security for which agencies have an entry point are placed and in the outer circle the overall operational context where protection issues exist are identified. Issues such as targeting vulnerable members of the community, collecting Sex and Age Disaggregated Data (SADD), ensuring nondiscrimination and impartiality by engaging community members across gender, age, diversity (such as people with disabilities, ethnic minorities) in community consultation, decision making and representation, setting up protection mechanisms in various interventions (reducing risks of GBV, child labour, exclusion, exploitation of labour/land rights and other threats) and making those accessible to all are some of the issues that fall within the inner circle. These issues have a direct bearing to gender equality programming. However, this model is still fully not applied in Afghanistan, although a few WFP staff members have been trained. Nonetheless, WFP reports that the implementation of this model has been included in WFP’s annual plan for 2013. Key findings Project cycle 4. Assessment and risk analysis - - - Sex and Age Disaggregated Data (SADD) collection varies across agencies, while a few of them collect SADD during baseline survey; a few maintain disaggregated records only of the selected beneficiaries. SADD of the overall community provides an overall picture and SADD of project beneficiaries provide information on what percentage of the overall populations, broken down by sex and age, have received assistance. In the absence of this correlation, it is difficult to get a grasp of what assistance was provided to whom in a given community. Agencies also mention that collection of SADD is a resource intensive process. Those few agencies that are collecting SADD as a part of their needs assessment are doing so because of donor requirement. Integrating protection into programme designing implies ensuring that protection risks associated with the interventions are identified at an early stage and addressed or mitigated in a systematic way. Protection, within the context of food security, has a wide range of issues but the risk assessments are mostly focused on security situation. While the security situation is critical it is not always linked with impact on gender; besides other aspects of protection, especially relating to Do No Harm, and identification and referring to protection risks, are not being systematically or consistently addressed. 5. Targeting and beneficiary selection - - - - Beneficiary selection and targeting takes places mostly with Community Development Councils (CDCs), which is in line with National Solidarity Programme’s efforts for decentralization and building the capacity at the grassroots. Nonetheless, many agencies said that there are significant challenges, including protection risks such as illegal taxation, with beneficiary selection through CDCs unless a thorough mechanism for verification is put in place. Furthermore, there is confusion over the selection process in relation to gender, age and disability. The problem many staff members face in determining selection criteria stems from lack of clarity on determining degree of vulnerability. Questions such as who is more vulnerable: a female headed household that receives remittances from outside or a household headed by an older man with limited physical capacity to work? Good practices: Oxfam GB, along with its partners OHW measures vulnerability as number of dependents versus ability to work and resources; ACTED social safety net methodology, ActionAid Participatory Vulnerability Analysis: all these targeting methods focus on the intersection between household criteria and socio-economic criteria for beneficiary selection but are time consuming. 6. Protection concerns in delivery modalities - FSAC members mentioned that a large number of affected populations still do not have Tazkera, so in the majority of cases, beneficiaries’ identity is verified by the CDCs and village elders. However, for IDPs, UNHCR registration process also helps in determining identity. Therefore, for large scale blanket General Food Distribution, verification of identity can pose a significant challenge as opposed to more specifically targeted projects for smaller groups of populations. - - - For some other kinds of food assistance and cash transfer, a few agencies could issue identity cards to the selected beneficiaries. Some partners reported to have issued identity cards with pictures of both males and females, but others issue identity cards with pictures only for males. Food distribution and cash distribution needs thorough protection analysis and the preference for modality differs from place to place. In some places, face to face distribution of cash and food is preferred over distribution via CDCs. Many times “safety” takes over “access.” FSAC agencies emphasizes the importance of having clear and transparent communication with community leaders as their support is crucial in not only in creating a positive environment for the implementation of projects but also for ensuring a protective environment for various disadvantaged groups to feel safe when participating in those activities. Oxfam GB mentioned the need to set up and train “dialogue teams” for diffusing tension with community elders. 7. Monitoring process and complaint mechanism - - - - - - - 1 There is a definite indication that food security interventions also contribute to a protective environment. As demonstrated by the Post Distribution Monitoring and other reports, with lessening burden on families through various food security related interventions, there are greater chances of easing intra household tensions. The safe livelihood approach used by NRC as one of the ways to provide a protective environment to individuals that are at risk of GBV is another example of enhancing protection A number of protection issues around food security interventions are mostly anecdotal rather than supported by concrete data. Child labour issues have reportedly been identified in some of Cash for Work and Food for Work activities. There has been feedback that boys dropped out of school in a few areas, discouraged by the incentive given only to girls. However, it is unclear if the boys dropped out of school to take up the responsibility of herding cattle for their families or if there is really any direct relation to girls getting incentives to attend schools. A significant and recurring protection threat faced by the beneficiaries is the demand for taxes (which as per some reports can be upto 80% of the cash transfer) by the CDC members and other community leaders. In this case, those households that are especially vulnerable such as the female headed, or headed by older people, people with disabilities and IDPs have no choice but to share their benefit from the project with the CDC, which implies that the intended benefit of the project will not meet its purpose. There is also lack of data to clearly demonstrate the cause and effect between food security interventions and Gender Based Violence. HAWCA reported, over 80% of the GBV cases are because of domestic violence, whether there is any correlation between food assistance and incidence of domestic violence is not established. There is evidence that women’s increased participation in public fora have made them more vulnerable to threats, harassment and aggression, mainly due to society’s rejection of females being active outside their homes.1 There is also an indication that when women, older people or people with disabilities have to depend on other community members for transporting their food items or cash, there is an underlying protection risk of getting those services/assistance in exchange of “favours”. There is also a gap in picking up indicative data from various assessments and to explore further to verify those with a strong protection component. For instance, the EFSL 2012 (draft) indicated that girls under 05 years and older people over 65 years are the most food insecure groups given that their household consumption rate is in the negative. However, both these groups are “supposedly well looked after” by family and community support as per traditions. However, such findings have not been discussed further to identify reasons why these groups are worse off than many others, in Protection and GBV mission report. WFP. 2009 - - the face of extreme poverty and resource crunch, is there a breakdown of family support system for the children, older people and people with disabilities Food access and quality has also been identified as one of the top three protection priorities. IDPs’ inabilities to meet their food needs forced them to resort to several negative coping strategies: reduce the quality and quantity of the food, entire day(s) without eating and restrict consumption by adults in order for small children to eat. UNHCR identifies the most vulnerable members among the IDPs as Persons with Specific Needs, but as already reported in an earlier chapter, often times the delay in providing food assistance to such people due to the paperwork involved pushes them further into adopting negative coping mechanisms. Many FSAC members, even after capturing or identifying protection issues from their monitoring process do not know how to take these cases forward for further action. Similarly in cases of abuse and neglect of individuals (especially in the case of older family members, or those who are sick and disabled), there is not enough knowledge on how to address these issues. Preliminary Recommendations - - - Promote available resources on protection, especially those relevant to food security, by holding short introductory sessions in FSAC meetings. Integrate brief sessions on gender and protection in the FSAC training calendar. For example, in trainings for proposal development, introduce a session on gender and protection analysis. Integrate overlapping issues of age, disability and protection in gender trainings. Maintain a roster of gender and protection trainers for inter-agency use Maintain a calendar of trainings held by various agencies across Afghanistan for appropriate linkages and sharing of resources. Organize trainings on humanitarian standards, gender, age, protection at a Cluster level by linking with various well know trainings such as IASC training module on gender, HelpAge training module “HOPE: Helping Older People in Emergencies,” and RedR ToT on Sphere standards. Set up simple referral mechanism for identified protection cases from food security interventions. Consider including network of CBOs, NSP CDCs, paralegals, Reflect Circles and other available protection resources in 3W and disseminating the information to various FSAC agencies. Common grounds in age, gender and protection mainstreaming Protection Age and disability Gender - - - Collection, analysis and use of Sex and Age Disaggregated Data to inform programming Gender and protection Inclusive needs assessments Targeting methodology Needs based interventions Accountability to Affected populations including feedback and complaint mechanisms Referral pathway for identified cases Humanitarian standards