as a word document

advertisement

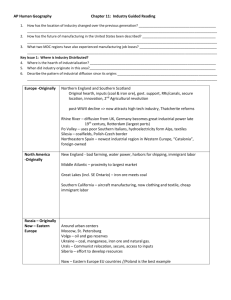

9ISS Tour = Special Access to Textiles + Experts In China by Amy Putansu, as published in Surface Design Association’s newsblog Travel to China from almost anywhere is no small undertaking. Organizing a truly open international symposium-meaning any participant can simply register to attend without institutional invitation or approval – has little precedent in this part of the world. In Fall 2014 – now almost a year ago – I undertook the journey to China to attend just such an event – From the Silkroad to the World: 9th International Shibori Symposium (9ISS) in Hangzhou. What follows is an overview of that once-in-a-lifetime experience, plus some reflections on what was, for me, a career-strengthening endeavor. Created by the China National Silk Museum and the World Shibori Network (WSN), the 9ISS platform for the exchange of research findings, professional opinions and artistic accomplishment was both unprecedented and exceptionally rewarding for the many scholars in the field of textile archeology and history, educators from art and textile institutions and leaders in fashion and design industries in both China and abroad who attended. Co-chaired by Ms. Yoshiko I. WADA of WSN and Dr. ZHAO Feng of the China National Silk Museum, the 5-day program included ancient, ethnic, and contemporary textile art exhibitions, workshops, demonstrations, a craft bazaar, gallery talks and dance performance by primary school children in addition to panel presentations and seminars. An international student competition organized by Dr. Kinor JIANG of Hong Kong Polytechnic University’s Institute of Textile and Clothing, a largescale outdoor fiber art installation by Prof. SHI Hui and students of the China Academy of Art and the Gambiered Silk Fashion Design Project by Ms. LIAO Xuelin of the Art Institute of Foshan were highlights – among many other remarkable events. (Find complete information, list of participants and additional photos at shibori.org/iss . Download pdf files of all papers via Symposium Proceedings at 9iss.wordpress.com/proceedings2). Carefully planned pre- and post-conference tours were also available to help attendees gain the maximum benefit from special access to the Far Eastern country where one of the oldest civilizations was born. I opted for the pre-conference tour. I’ve been teaching textile history and world textiles for a few years, educating myself primarily through texts. Traveling with renowned textile scholars, historians and artists from around the world provided an opportunity to interact with more intimacy than a typical conference setting might allow. This kind of special access is a regular feature of ISS tours. This one included visits to museums, collections and studios that were well designed for examining aspects of culture and textile traditions unique to China. They complemented the symposium proceedings while offering a broader view of areas surrounding Shanghai and Hangzhou, plus a glimpse of contemporary Chinese culture and living conditions. Once the largest city in the world (in 12-13th century during Song Dynasty era), Hangzhou’s West Lake Cultural Landscape has been listed as a UNESCO World Heritage site. The pre-conference tour participants left their Shanghai hotel to embark upon a tour (via bus) to JinZe Arts Center located in JinZe Town on the outskirts of Shanghai. Its 1300+ year history give its waterways, canals and bridges significant historical resonance. JinZe Arts Center itself is a maze-like, mysterious compound of many structures that provide spaces for studios, workshops, research and an archive of over 5,000 objects. The center can accommodate up to 50 people, so this is where participants stayed for the 4-day tour. Since the center is in its early stages of development, our pre-conference tour group was the largest the facility had served thus far. The environment is spare and remotely temple-like, with beautiful interior and exterior details. There are plans for an artist-in-residency program, exhibitions and studios in a variety of media. The arrival at JinZe was thoughtfully choreographed to provide optimal transition into the new surroundings. Participants divided into 2 smaller groups in order to tour the small town, part way on foot and part way by boat along the canal. On the boat ride, Chinese traditional song was performed as we floated back to the arts center. The afternoon was spent in the impressive textile archive room at JinZe. Textile division director Ms. Edith Cheung presented a number of objects from the collection relevant to the symposium and excellent examples of Chinese tradition. Cheung pointed out only natural dyes – except the purple – were used on this dragon robe. The cloth is constructed of a very fine silk tapestry weave or kè si. The ‘horse hoof’ design of the cuff was among modifications made in the 19th century to accommodate the activity of horseback riding. The weaving studio is the most complete and operational facility at JinZe. Looms are primarily traditional Chinese handlooms from the JiangNan area – the type used by villagers. When there was a ration on commercial cloth in the 1960s, a great deal of simple cotton plain weave cloth was hand woven on this type of loom for everyday use, like bedding and clothing. A special pre-tour feature was presenter Dr. Tomoko Torimaru, a scholar of Miao, a Chinese minority group known for complex traditional costume. After delivering a presentation on specific Miao textiles in the JinZe collection, she guided participants through hands-on projects demonstrating a primary Miao technique akin to kumihimo braiding. In Miao textile construction, these carefully braided lengths would then be couched onto garments, baby carriers and other textiles in highly decorative patterns. Other activities included working with tu bu, a type of Chinese hand woven cotton folk cloth. Tu bu is the simple cloth of rationed-era China that would be made on looms like the ones in the JinZe weaving studio. The plain weave structure of tu bu exemplifies limitless variations of beautiful colorand-weave effects. In the evening, guests were invited to a traditional tea ceremony. It was presented by an elegant young Chinese woman, studying to be a monk, who was an expert at tea ceremony. Next stop: Nantong City on the north bank of the Yangtze River, across from Shanghai. During the Han Dynasty (206-220 AD) the town was known for producing salt. Nantong is also famous for the traditional textile technique of blue calico as well as several types of embroidery each considered to beintangible cultural heritage. Intangible cultural heritage is a term used by UNESCO to describe aspects of culture like skills, music or other expressions that are recognized by the population and the government to be culturally valuable in a nonquantitative sense – and therefore worth protecting. Blue calico is a cotton textile with white patterning on an indigo ground. The patterning is achieved by printing a resist-paste onto the cloth made of soybean powder and lime. This paste dries for a long period before indigo dyeing. After dyeing the paste must be scraped off to be fully removed as it is not water soluble. This technique originated during the Tang and Song dynasties (6181297AD). Tour participants witnessed blue calico from several perspectives on a day trip to Nantong. Artisans specialize in each aspect of the process that begins with the cutting of pattern stencils by hand. The paper stencil is made waterproof with a coating of tung oil. At a second studio, 2 artisans worked skillfully together printing the resist paste onto meters of cotton cloth. In this large studio, many lengths of printed cloth hung draped in rafters to dry. Also located in this space were the large indigo vats for dyeing calico. The experience of blue calico was made complete at China Nantong Blue Calico Museum. Chinese art master and many-generation indigo dyer Dr. Wu Yuanxin founded the museum in 1997 with a collection reported to consist of over 26,000 blue calico fabrics. On view are tools and equipment involved in the making of blue calico, including a cotton spinning wheel and several looms on which demonstrations were offered. Day 4 of the tour included the city of Suzhou, about 70 miles west of Shanghai. Suzhou has been associated with silk production since at least the 13th century. The artisans of the region are famous for silksu (short for Suzhou) embroidery, one of the China’s 4 traditional styles. Su embroidery consists of satin stitch using very fine silk thread. The most famous variation of suembroidery is executed on sheer ground cloth and is double-sided, or shuang mian xiu. This is the type most practiced atSuzhou Embroidery Research Institute of China. Also considered an intangible cultural heritage, the practice of Suzhou embroidery is studied at the center with a master/ apprentice approach. The studio stretched for many rooms with multiple work stations, each with pieces in various states of completion. The studio tour ended in the gift shop where framed and mounted embroideries were presented in dramatic lighting. Nowadays the primary audience for this kind of work is the tourist market (think koi fish, tigers and peacocks), but during the 12th century su embroidery was used to produce wall pieces that functioned like paintings. By the Qing dynasty (1644–1912) embroidered textiles of all types were used by the imperial family. The investigation and analysis of blue calico and other intangible cultural heritage textiles continued throughout the main symposium. The insights offered through first-hand experiences on the pre-conference tour provided an invaluable foundation, and indeed turned out to be unforgettable, life-changing travel in China. I have witnessed culturally unique textile practices in the presence of expert travel companions! Together we shared extraordinary experiences, including studio and location visits, normally inaccessible but for the influence and networking magic of WSN and Yoshiko Wada to seek out and arrange. From those authentic and personal exchanges we moved directly into the formal symposium. The experience was rounded out with museum exhibits of historical and contemporary textiles and lectures delivered by the leaders in our field. I can’t imagine another way to receive such a broad perspective on not only shibori, but also the larger, global movement toward sustaining textile traditions and cultural resources. The very existence of 9ISS underscores the fact that the global textile community cares deeply about education – as we looked closely at the past, the present and into the future of these traditions.