Amanda Garrett DRAFT 2: Research Proposal (December 3, 2010

advertisement

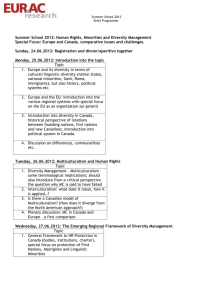

Amanda Garrett DRAFT 2: Research Proposal (December 3, 2010) Muslims and their Localities: Explaining Variation in Policy Response I. Introduction: The Puzzle Today across Europe, which has experienced large-scale migration from the Muslim world over the last half-century, the debate about the integration and accommodation of Muslim minorities is becoming an increasingly salient political issue. For example, the past electoral success of Jean-Marie Le Pen in the 2002 French presidential elections, the late Pim Fortuyn’s party in the 2002 Dutch parliamentary elections, recent 2010 Parliamentary success of the Dutch far-right Party for Freedom (PVV) making it the third largest party in the Netherlands, and similar successes in Denmark, Belgium and Austria have signaled the rise of the xenophobic right and the increasing politicization of the Muslim issue. The already tense relationship of these Muslim communities to the larger society has been further exacerbated by heated debates surrounding the affaire du foulard and the Burqa in France, Holland and Germany, Mosques and Minarets in Switzerland, Germany and France, and 2005 riots in France and the assassinations of Pim Fortuyn and filmmaker Theo van Gogh in the Netherlands. These events, which seem to be indicative of an increasingly hostile and sometimes violent interaction between Muslims and national groups, also suggest that the presence and integration of these minority groups continues to be viewed with skepticism from both sides. This is largely the assumption present in the literature, that the integration of Muslim minorities has not been a stellar success anywhere in Europe, which is not an unrealistic conclusion given the scope and abstractness of most studies on minority incorporation that rely on “national model” and minority characteristics to explain outcomes. However, only a more nuanced and systematic study of how policy gets made at all levels of government – not just the national level – will indicate that the relationship between the state and its minorities is not so monolithically negative. So there are two important points to take away from this observation. First, it is crucial that we understand the mechanisms behind success and failure because they are empirical realities, the causes of which are still not well known. Second, we need to study this success and failure at the local level, where minorities and policy-making bodies are more likely to interact in ways that are most salient to their daily lives and ultimate integration. There is a great deal of variation in the accommodation and treatment of Muslim demands and needs across Europe’s cities that can never be captured by restricting analysis to national-level or minority-specific variables. So while extant research understands the general trend in policy responses to minorities to be predominantly the result of these two factors, this dissertation will demonstrate that a closer look at what happens at the local level may force us to alter our understanding of both how these national models work and how “successful” and “unsuccessful” policies are made, where success is defined as a fair, representative and well-intentioned process. Amanda Garrett More specifically, it is clear that the literature on national models of minority integration is by far the most prevalent means for explaining policy responses – at some level, most outcomes are being traced back to these historically embedded ideological and institutional mechanisms for dealing with minority groups. And while there is no doubt that these national approaches are an integral part of minority policy, they are too often treated as inflexible paradigms or abstract concepts of policy-making and therefore, fail to provide an adequately nuanced picture of the possible range of policy responses that will give justice to the diversity of minority treatment in these countries. For example, much of the research on integration constructs either real or metaphorical integration index scores and rankings of host societies based on their “success” in one or more policy sector (Cinar, Davy and Waldrauch 1999) where any deviance risks being construed as a negative result. Similarly, inherent in these studies is a problem with the level of analysis, where a bulk of these studies have looked at the nation-state, leaving only a paucity of work on the urban or city-level context of minority policy responses. In short, this project is motivated by two primary observations stemming from this national model literature. First is the problem of intellectual approach, where relying on theoretically driven notions of fixed national responses to minorities often misses important nuances in the policy-making reality in these countries. Secondly, beginning at the national level can present an empirical problem when understanding integration or policy success as there is reason to believe that success along these measures is more likely to begin at the local, not national, level. This is an important oversight because in some cases it is clear that the local level is more important than the national level, where the city or municipality is the main location for all citizens, including Muslim minorities, to make demands on and claims to a range of municipal services from housing, to schools, to labour markets and politics. It is these factors that ultimately affect the daily lives of Muslims in Europe; it will help determine educational and linguistic attainment, socio-economic status, spatial segregation and contact with non-Muslims, and their interest and engagement in civic and political activities. In response to these demands, cities have formulated a variety of pro-active and reactive minority policies using their own instruments and resources (Ireland 2008). In short, municipalities have enacted policies to make minorities feel at home or to encourage them to leave - ranging from antagonistic to supportive. None of this variation can be captured, much less explained, if the focus is on national-level variables, which is what this dissertation seeks to remedy. The impetus for this project therefore arises from the desire to create a more intellectually nuanced and empirically representative picture of what determines an instance of positive policy response to Muslim minorities, which is something that is high on the agenda of policy-makers and academics alike. The literature has often taken for granted the usefulness of local variation in learning how minorities are treated in a given country, preferring to focus on the better understood and more systematically accessible national level factors. Yet, the vast diversity of institutional, structural and ideological approaches used to deal with Muslim minorities that we see across European countries has categorically failed to reproduce itself in subsequent differences in outcomes of policy or integration. So we need a more nuanced way to understand certain policy outcomes, Amanda Garrett where national model effects actually manifest themselves in the policy process, and what other processes are involved in the process, all of which can be done by changing the unit of analysis to the city. The research design is case-oriented and methodology is qualitative and based on interviews collected in the field as well as access to secondary and primary sources. The burden of causal inference will rest on a systematic process analysis of policy responses to Muslim minorities in Paris, Marseille, Amsterdam and Rotterdam. Cross-case comparison reveals two cases of positive policy response (Marseille and Amsterdam) and two relatively less positive cases (Paris and Rotterdam), and I have selected these cities for two methodological reasons. First, it allows me to hold national policy and structure (i.e. national models) constant while varying local instances of success and failure, and second, I will be able to hold local success constant and look at variation in national policy and structure. The insights from this dissertation should illuminate they ways in which successful and less successful policy responses towards Muslim minorities are formed. By looking at city variation, I go beyond “national model” descriptions of minority policy-making and attempt to explain not how national approaches to integration policy differ across countries, but rather how they differentially affect local policy resources and instruments to produce outcomes that are immediately relevant to the daily lives of Muslims in Europe. The rest of the prospectus will follow in four parts: the literature review, theory and hypotheses, research design and cases, and feasibility. III. Theory and Hypothesis It is not a surprise that the experience of Muslim minorities differs greatly across country and even between cities, which makes comparative analysis across cases of prime importance for understanding how institutions should be molded to make them more responsive, and how cities stimulate minorities to find a suitable place in society for political, social, and economic participation and integration. There have, of course, been many studies that seek to answer these questions, but they tend to be too abstract, theoretical, normative, or national-level specific to inform us about the local and contextualized forms of inclusion that shape Muslims’ daily lives. In this respect, cities have quite a unique responsibility towards minorities, one that is distinct from the national level (Penninx et al. 2004). If we want to understand how local governments respond to Muslim minorities’ presence, how minorities place themselves in the political arena and how this affects policy outcomes, there are two possible routes - top-down and bottom-up - and all of the proposed hypotheses will help distinguish the importance between these two lines of argument. The first top-down approach refers to the dimensions of policy-making that emanate from the power of the state, both national and local. This includes the institutional, structural and ideological framework within which national and city administrations enact and implement minority policies, as well as the state actors Amanda Garrett involved in the process. All of these variables help highlight how open or closed a given society will be to the minority needs and demands presented to them. Alternatively, the bottom-up approach will allow a closer look at the actions of minorities themselves, including the degree of their mobilization, their political and organizational resources, their requests and claims on the local and national administrations, and ultimately their impact on policy outcomes. When it comes to determining the relative importance of these two arguments, is impossible at this point to say which is more important (or which variables are more important) because none are truly independent from one another. The policy-making process necessarily includes a combination of top-down and bottom-up factors and operates in terms of a complex feedback process, so the goal should be to try and untangle these potential explanations. I would like use both approaches to explore the conditions under which localities respond to the needs and demands of their Muslim minorities and the reasons for variation in response across locality as well as policy domain. By focusing on an array of local government responses to Muslim minorities – symbolic politics, government rhetoric, policy making and outcomes – it is possible to capture the relationship of the locality to its minority as a multidimensional process. I intend to argue that nature of local authority response and interaction with Muslim minorities depends largely on their perception of the potential costs and benefits of different kinds of responses, namely positive, negative, or avoidance. The localities’ evaluation of the potential costs and benefits of different policy responses may be influenced by a variety of factors, including surrounding institutional arrangements and structural factors, such as national models of immigrant incorporation, electoral systems and political parties, or government structure and its impact on policy jurisdiction and implementation (i.e. centralized vs. decentralized state). However, it should be noted that while these institutional factors cannot be ignored, the case selection of this study helps us control for the impact of these variables by themselves, so while they are no doubt important, they are not singularly responsible for the outcomes we see. Instead we must consider additional factors such as the character of the local Muslim population, which may also affect the cost-benefit calculation if they are particularly active in politics (Garbaye 2002) or have strong and vocal social networks (Pfaff 2006), the city’s historical relationship with immigration, and local policy-makers’ personal ideologies. Overall, the more confident local policy-makers can be that responding favorably to its Muslim population will strengthen its political, economic or ideological position, the more likely they will be to seek the potential benefit of such a response, which might include policy measures, symbolic action or rhetoric. Conversely, if local authorities fear that positive engagement will undermine their political, economic or ideological position, they will opt for more negative policy, or avoidance. Policy-makers, however, do not operate in a vacuum and their decisions will be colored by some combination of the aforementioned factors. It is the goal of this study to seek to identify conditions and combinations of factors - both from the state and the minorities themselves - under which pragmatic considerations favor positive, negative or evasive responses. Amanda Garrett First, I will mention a few alternative explanations that are prevalent in the literature, not because they are untrue or irrelevant, but because they are not sufficient to explain the variation in local success and failure in which we are interested. Alternative Hypotheses: The predominant overture in the literature on Muslim integration is to focus on the importance of varying national models of state-minority relations. Differences in policy outcomes and official rhetoric towards minorities across countries have largely been attributed to the historically determined and path dependent set of ideological, institutional and structural responses to diversity unique to each state, called the national model (Fetzer and Soper; Soysal; Brubaker; Koopmans and Statham). This literature has been used to understand the governance of Islam in Europe, namely the way in which society creates or stifles opportunity for the development of Islam. There is no doubt that these national approaches to minority integration help us understand the process of policy-making, but they do not tell the whole story. First, the national institutional and ideological framework for dealing with minorities is not all-powerful and it likely has unintended, counterproductive and residual effects across levels of government and policy domains that cannot be captured by looking at national models alone. For this reason, the case selection of this study, which looks at one set of successful and less successful instances of local policy outcomes across two distinct national contexts allows us to look beyond the solitary impact of national models. Another set of explanations used to illuminate the relationship between state and minority focuses on the characteristics of the minority group themselves, where the religion, culture and class of the minority matter. According to these theories, a minority’s common class identity (Castles et al 1990) or ethnic or racial identity (Miller 1990) is of fundamental importance in determining their participation in and interaction with the system. A subset of this literature looks specifically at Muslim minorities – their internal structure and culture, the formation of associations and the development of identities – and how this affects their position vis-à-vis the state. Again, one cannot discount the relevance of minority-specific characteristics, yet they can tell us nothing unless we understand how they are restrained or encouraged by societal factors. To help us separate the impact of group-specific variables, this study will look at city couples with the same minority compositions – Turks and Moroccans in the Netherlands and Moroccans and Algerians in France. Hypotheses: Amanda Garrett Based on the idea that local responses to Muslim minorities are the product of costbenefit analysis on the part of local leaders who are forced to act amidst a variety of topdown and bottom-up forces, I would like to test the following hypotheses: 1) Ethnic minority policy is a distinct sector of policy-making with its own local dynamics, which cant be explained using national-level factors alone. It is the result of social forces and institutional design within that sector, which may be different from urban or national factors. 2) When the Left is in the opposition, instances of positive symbolic politics and rhetoric will likely increase. When the Right is in the opposition, instances of negative symbolic politics and rhetoric will likely increase. Borrowing from the literature on social movements, we see that the party system and distribution of power can affect the treatment of the movement, and it is possible that the same factors at play here can influence a state’s treatment of minorities. For example, like social movements, it is theorized that minority constituencies belong to the electoral potential of the Left, in which case the position of the left in politics may impact local governmental responses to Muslim minorities. If the left is in the opposition, we will likely see more instances of symbolic politics or positive rhetoric towards Muslim minorities as they seek the support of this demographic and conversely if the right is in the opposition, there will likely be more instances of negative rhetoric in an attempt to target their constituency. In short, when in a position of opposition the parties will tend to address Muslim minorities primarily in terms of symbolic politics and political rhetoric – the political tools available to them – rather than policy outcomes, and these actions will reflect their need to target certain constituencies, where the Left will lean towards positive responses and the Right towards less positive responses. 3) When the Left is in power, instances of positive policy should increase and when the Right is in power, instances of negative policy, or avoidance should increase. When the Left is in power and in a better position to propose and implement policy, there should be an increase in the likelihood of proposed and successful policies benefiting Muslim minorities, which are an important fraction of the Left’s constituency. Instances of symbolic politics and positive rhetoric should continue as they are a useful component of the party’s political toolbox and the Left cannot afford to lose the support of its constituency between elections. Additionally, from the literature on redistribution and political parties, we know that the Left is more prone to engage in redistribution, a policy which may be more favorable to minorities in the community, and the Right less prone to such policies; therefore, this is an additional indication of the potentially beneficial outcomes for minorities when the Left is in power as opposed to the Right (Iversen and Soskice 2006). Similarly, for the Right, with policy-making now one of their political Amanda Garrett resources, while in power instances of policy that negatively affects Muslim minorities, or avoids them altogether should increase. 4) When in power, the ability of a party to negotiate for policy towards minorities will be affected by their position (i.e. whether they are governing alone, or part of a coalition). Building from the previous hypothesis, one would expect that the nature of the policy or the amenability of the Left to making concessions to this group should also be affected by its position in government – i.e. whether it is part of a governing coalition or not – as this will impact its ability to negotiate policy. If the Left is governing alone, there will likely be a better chance they can initiate positive policy responses unhindered by a minority coalition partner, but if the Left is that minority coalition partner, they may be limited in their ability to make policy concessions to this constituency. The same will be true for the Right, except with respect to less favorable policy for minorities. Again, borrowing from the literature on electoral systems and political parties, it is clear that the type of electoral institution present in a given polity can affect which parties get into power. For example, in polities with systems of proportional representation Left parties tend to dominate, and the likelihood of a governing coalition is much higher, whereas in majoritarian systems, Right parties tend to dominate, which in turn could be linked to expected policy responsiveness to minorities (Iversen and Soskice 2006). 5) How and to what extent Muslim minorities participate in the political process impacts policy outcomes. The higher the rate of enfranchisement, the proportion of minority representation in local councils, position as mayor, and the support local Muslim organizations receive from established political pressure groups should all (independently and in tandem) increase the instances of positive policy responses from the local administration. As we have seen, the majority of literature on immigrant incorporation has been devoted to describing policy instruments (Hammar 1985), assessing outcomes (Doomernik 1998), making cross-country comparisons to explain national models of integration (Castles 1995; Favell 1998; Schnapper 1992), explaining the content and development of national integration policy and those involved (Guiraudon 1998). And similarly, a majority of these works take a top-down approach, like examining the role of elites (Katznelson 1976; Messina 1987) because they rest on the assumption that minorities are usually too weak to make significant claims on the political agenda (Martiniello 1994). This hypothesis stems from the idea that bottom-up activities may matter in the policy-making process. Specifically, from the literature on minorities and politics in Europe we know how the institutional structure of a given society can encourage or hinder minority participation in Amanda Garrett the political process, but there is much less known about how minority participation impacts policy. However, from scholarly work on minorities in American politics there are instances of black Americans pushing important policies for their own communities once elected to local office (Browning et al., 1997) and of the importance of descriptive representation in Congress as a more symbolic measure to ensure a continued presence of that minority in the legislative process (Swain 1995). When it comes to Muslim minorities in European cities, there is a range of possible participatory forms to study, including office holding, voting or membership in an ethnic organization with lobbying power. Because minority participation at the elected level is likely to be minimal in relation to non-minority participation and their influence tempered by other members of government or by the electoral process itself, it is possible that we see little impact from elected minorities on policy outcomes, where their presence is limited to descriptive representation only. Their substantive representation is more likely to come from the influence of ethnic organizations and the political resources of those groups vis-à-vis the system. Within the literature in American and European politics, there is a substantive body of work that links minority participation in the political process to positive outcomes and this hypothesis will consider these variables. For example, it has been shown that the presence of a minority mayor (Stein 1986; Browning, Marshall and Tabb 1984), local council representation (Haider-Markel et al. 2000; Mladenka 1989), ability and willingness to vote (Garbaye 2002), and the capacity of minority organizations to gain formal support of political pressure groups (McClain 1993) all increase the chances that policy response towards minorities will be positive. 6) The structure and “culture” of government, and the subsequent division of policy jurisdictions will affect a city’s policy response to minorities, where minorities will fare better under unreformed structures than under reformed ones. The structure of government – centralized vs. decentralized, reformed vs. unreformed – impacts how policy is made and who makes it. Already in the European cases we see a distinction between types of government patterns of policy making through the literature on national models, where the French assimilationst regime is highly centralized when it comes to immigration policy and the Dutch multicultural regime is centralized, but allots a significantly higher degree of power to local governments. Similarly, policy reports on these two countries highlight the central role of the national government in France, which permeates almost every level and arena of policy-making, leaving local authorities rarely completely autonomous in their actions, whereas the Dutch localities are largely independent to produce and implement policy towards minority free from the intervention of the national regime (OSI 2007). And while there is not much systematic work in the European cases about the consequences of regime type on minority policy, the American literature provides some useful analogies. Amanda Garrett From this literature we know that the U.S. government reserves most of the power in the arena of immigration policy (status setting, entry policy etc.), but still city governments are allowed to handle policy in the social domain and deal with minorities in ways that are distinct from the national government according to their jurisdiction - like distributing services (Hero 1986), dispersing federal monies to organizations and projects (Hero 1990), and employing minorities in civic service (Hero, 1990; Eisinger 1982; Karnig and Welch 1980). There is still a debate in this literature about the implications of this division of jurisdictions and whether the national or state government is “nicer” to minorities. Some scholars find that the federal government and Congress tend to me much more amicable when it comes to minority policy than the state governments, which largely enact “symbolic policies” to curb minority rights (i.e. bilingual education) (Sartoro 1999) or simply shy away for moral or racial policies in favor of fiscal management (Eisinger 1998). Others, however see the opposite, where U.S. states have often bestowed additional rights (driver’s licenses) or simply not cooperated with federal sanction policy (Schuck 2007). Either way, it is clear that the structure of government prompts variation in policy response at different levels, and it is the hope of this hypothesis to analyze this distinction in the European case. One place to start is with the distinction between reformed and unreformed systems made by Eisinger (1982), which helps explain variation in city institutional configurations and cultures. In reformed cities where the goal is to keep “politics” out of the administration, political competition and pluralism are minimal and there is much tighter central control over policy, which is quite closely linked to the idea of a traditionalistic culture (Elazar 1984). Conversely, unreformed cities are more politically competitive and the system is more open to minority participation and voice, which is more reminiscent of an individualistic political culture where politics is a marketplace for ideas. These authors find that minorities tend to fare much better in unreformed and individualistic cities and much worse in reformed and traditionalistic ones, and examples of this can be seen in the case of Europe. For example, in Paris – reformed and traditionalistic - until the late 70s the city was ruled by a prefect where the national government reigned stronger than municipal efforts, particularly in immigration policy, where local outcomes reflected national decisions. Presentation of Preliminary data