Research and Innovations in Medical Education

advertisement

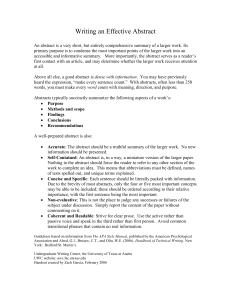

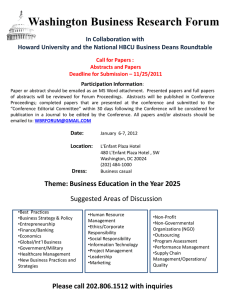

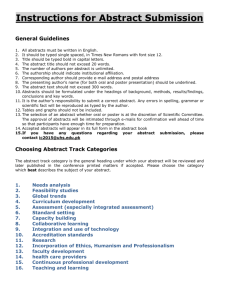

RIME Week: Research and Innovations in Medical Education Poster Session – Call for Abstracts Submission Deadline Friday, August 16, 2013 Wednesday, September 25th, 2013 1:00 – 3:00 pm - West Pavilion Atrium (1st floor, West Pavilion) UAB 3rd Annual Medical Education Summit Research and Innovations in Medical Education (RIME) Abstracts The goals are to stimulate collaboration and creative thinking and to highlight innovative scholarly activities in medical education. Projects or work in progress may be presented with the purpose of obtaining feedback from the audience. Eligible projects include the development, implementation, or evaluation of innovative courses, curricula, assessments, simulations, internet-based tools, or interdisciplinary health education collaborations. Submissions may fit one or more of the following categories: Continuing medical education Medical student education Curriculum development Postgraduate medical education Education innovation Professionalism Faculty /program evaluation Quality and safety Learner assessment Simulation Clinical Vignettes Abstracts Vignettes should be based on patients for whom at least one of the author(s) had cared for during the course of the patient’s illness at UAB. Clinical vignettes should describe clinical conditions that illustrate unique or important teaching points, provide insight into clinical practice, education, or research, illustrate important clinical problems such as diagnostic, therapeutic, or management dilemmas. Eligibility All members of the School of Medicine: Research and Clinical Faculty, Residents, Fellows, Post-doctoral Scholars, Graduate Students, and Medical Students. Abstracts submitted to other meetings for presentation this fall or presented at recent meetings are eligible. Abstracts from manuscripts not yet published are also eligible. Structure Word document, 1-page, Times New Roman 11-point font, 0.5” margins, maximum file size 300KB. Include: Name, Department, e-mail, Appointment/Position, and category (see example). RIME abstracts, include: Background/ Objectives, Setting and Participants, Description/Methods, Evaluation/Results, Discussion/Reflection. Clinical vignette abstracts, include: Learning Objectives, Case Presentation, and Discussion. Accepted abstracts will be presented in poster format (not larger than 48” x 72” in size). References are optional. Unless specifically requested by the submitting author, all accepted abstracts will be published online. Contact: Amanda Vick, MD (avick@uab.edu) or Sherry Morgan (ssmorgan@uab.edu) with questions Submit abstracts via e-mail to avick@uab.edu by 5pm, Friday, August 16, 2013 DIAGNOSTIC ERROR IN THE CARE OF SIMULATED PEDIATRIC INPATIENTS. Nassetta L1, Tofil N1, Youngblood A2, Zinkan J 2, Eschborn S3, Taylor-Peterson D1,2, White ML1. 1 University of Alabama at Birmingham, Department of Pediatrics, 2 Children's of Alabama, Pediatric Simulation Center, 3 University of Alabama at Birmingham, School of Medicine. Contact: Dr. Nassetta, Assistant Professor of Pediatrics (lnassetta@peds.uab.edu). Background/Objective: Diagnostic errors in medicine result in substantial harm to patients. Premature closure, the tendency to accept a diagnosis before it has been completely verified, is the most common type of cognitive error in the care of inpatients (Ely, 2011; Graber, 2005). Research shows limited use of simulation to evaluate diagnostic error and to teach the appropriate metacognitive strategies to avoid it (Bond, 2004 & 2005). The most recent literature in this domain is limited to emergency medicine residents and does not directly address premature closure. We hypothesized that premature closure could be demonstrated during simulation by residents on inpatient pediatrics rotations. Setting and Participants: Residents on their general inpatient pediatrics rotations participated in teams (PGY1 + PGY2-4) for a total of 65 participants. The simulations took place in the Children’s Hospital of Alabama Pediatric Simulation Center using Laerdal SimMan and Laerdal SimJunior. Description / Methods: Residents on their general inpatient pediatrics rotations participated in teams (PGY1 + PGY2-4) in simulated patient cases. Teams were randomized, and each team received two cases in which they were asked to evaluate and treat simulated patients. Residents received a text page at the beginning of each case with the location and a brief descriptive phrase regarding the patient. In one case, they were given a closed stem with an incorrect diagnosis and in the other they received an open stem with a symptom. The remainder of each case was scripted and identical. Cases were piloted prior to data collection to improve consistency. Stem: Session 1 1A “Asthma” Actual Diagnosis: 1B “Wheezing” CHF Cardiogenic wheeze 2A “DKA” 2B “Not feeling well” Sepsis Session 2 3A 3B “Croup” “Stridor” VP shunt failure 4A “Pneumonia” 4B “Abdominal pain” Appendicitis Data regarding history, physical exam, laboratory and radiological evaluation, treatment, and correct diagnosis was collected in real time by observers on a standardized recording tool. A scripted debriefing emphasizing cognitive error immediately followed each case. Comparisons between stems (A vs. B) were analyzed with Fisher’s test on 2x2 contingency tables. Evaluation / Results: Fifty-four residents participated in this study. Residents who were given the open stem either considered or made the correct diagnosis 86% of the time, while those who received the closed, incorrect stem considered or made the correct diagnosis only 72% of the time (p<0.05). Similarly, those who received the open stem initiated appropriate therapy more frequently than those who received the closed stem, at 60% and 53% of the time, respectively (p<0.05). Often those who received the closed stem initiated treatment prior to thoroughly examining the patient or reviewing key features of the disease. Discussion/Reflection: Premature closure can be demonstrated during simulated patient encounters in the inpatient setting. Residents who were given the open stem were more likely than those paged with the incorrect diagnosis to at least consider the correct diagnosis and begin appropriate therapy. Simulation provides an excellent venue in which to examine cognitive error with residents and to teach metacognitive strategies for avoiding it. References: Bond WF, Deitrick LM, Eberhardt M, et. al. Cognitive versus Technical Debriefing after Simulation Training. AEM 2006: 13:276-283. Bond WF, Deitrick LM, Arnold DC, et. al. Using Simulation to Instruct Emergency Medicine Residents in Cognitive Forcing Strategies Acad. Med. 2004: 79; 5: 438-446. Ely JW, Graber ML, Croskerry P. Checklists to Reduce Diagnostic Errors. Acad Med. 86:3, March 2011, 307-313. Graber ML, Franklin N, Gordon R. Diagnostic Error in Internal Medicine. Arch Intern Med. 2005; 165: 1493-1499. Category: Publish online: Research and Innovation in Medical Education (RIME) Yes No Clinical vignette