ele12279-sup-0003

advertisement

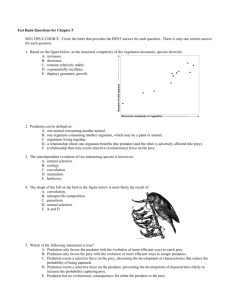

Appendix C. Additional results and considerations. Independent Variables There were a number of variables that could influence our results and conclusions, but were not included in our main results because they were considered less important. First, there was the possibility for taxonomic bias across the species interaction types. We categorized studies by broad taxonomic categories: plants, invertebrates, vertebrates, and other. There was uneven distribution of taxonomic groups across species interaction types (Table C1), but there was not adequate representation of data points across combinations of factor levels to perform an analysis on the role of taxonomic bias. Table C1. Percent of studies with the given taxonomic group in each of the three species interaction types. Taxonomic Group Species Interaction Type Predation Plants Invertebrates Vertebrates Other 1.4 75.7 19.4 3.5 Competition 54.1 35.3 10.0 0.6 Mutualism 80.7 16.7 2.7 0 Second, the mobility of species can differ, perhaps influencing our results. Eighty-seven percent of species were mobile in the predation studies, while only 41% were mobile in competition studies, and only 14% in mutualism studies. We asked if mobility influenced our results, and found that mobility did not qualitatively alter the results we found in our main results for CV as a response. We were not able to test for differences with sign change as a response because of too few data points across combinations of factor levels. Response Variables In addition to outcomes changing sign within a study (between any of: +, 0, and -), which we discussed in the main results of this study, outcomes can also flip. That is, outcomes can go from negative to positive within a study. This did not happen very often: less than 10% of studies for each of predation, competition, and mutualism. That competition can range into facilitation (from - to +) is not surprising there is much evidence that putative competition interactions can be facilitative in some circumstances, and vice versa for facilitation. Likewise, mutualism can grade into parasitism (from + to -) within a species interaction in some circumstances. However, it may be more surprising that outcomes can flip in predation, in which we would think interactions would almost always be positive for the predator and negative for the prey. However, some predation studies did flip in sign from negative to positive. We discuss a few examples to show how flipping of outcomes can happen in predation. First, Englund and Olsson (1996) asked if prey movements biased estimates of predator effects on prey. In data collected from Table 1 in the paper, outcomes flipped from negative to positive for among the different prey species that the same predator interacted with. Thus, outcomes flipped between different prey species. Second, Menge et al. (1999) found that outcomes in an interaction flipped due to different spatial contexts (=different sites). In data collected from Fig. 14 in the paper, outcomes between Mytilus galloprovincialis mussels and Stichaster australis seastars flipped from negative to positive among different sites. References Englund, G. and T. Olsson. 1996. Treatment effects in a stream fish enclosure experiment: Influence of predation rate and prey movements. Oikos 77:519-528. Menge, B. A., B. A. Daley, J. Lubchenco, E. Sanford, E. Dahlhoff, P. M. Halpin, G. Hudson, and J. L. Burnaford. 1999. Top-down and bottom-up regulation of New Zealand rocky intertidal communities. Ecological Monographs 69:297-330.