2. Deep determinants and the long

advertisement

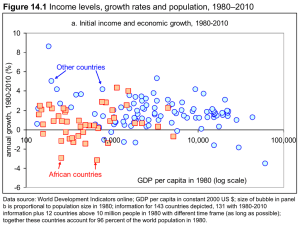

The rise of deep determinants Robbert Maseland, University of Groningen 1. Introduction In recent decades, explanations of economic growth have increasingly focused on deep determinants of differences in development (Spolaore & Wacziarg 2013). Contemporary differences in economic performance are related to institutional quality which can be traced back to historical events (e.g. Ashraf and Galor 2011; Dell 2010; Tabellini 2010) and natural circumstances (e.g. Ashraf and Galor 2013; Easterly and Levine 2003; Haber and Menaldo 2011; Sokoloff and Engerman 2000). This literature suggests that initial differences in formal and informal institutions tend to persist for long periods of time, only incrementally changing in response to further random events or changes in political interests (ARJ 2001; Francois & Zabonjik 2005; North 1990). Such institutional persistence subsequently provides a substantial part of the explanation for enduring income inequality between societies. Why do differences in institutional and economic development persist? Spolaore & Wacziarg (2013) identify biological transmission channels (Ahsraf & Galor 2013; Galor & Moaz 2002; Clark 2007) and mechanisms of cultural transmission (Bisin & Verdier 2000; Gorodnichenko & Roland 2010; Greif 2006; Guiso, Sapienza & Zingales 2008; Tabellini 2010). In biological transmission, members of a society inherit certain biological traits that impact development directly from their ancestors. Under cultural transmission, older generations transmit ideas, norms, values and beliefs to the newer ones through socialization. Stability may then come from interdependencies among economic institutions (Hall and Soskice 2001), between economic institutions, mental models and processes of learning (Bisin and Verdier 2000; North 1990, 2005), or between economic and political institutions (Acemoglu, Johnson, Robinson 2005). Institutions provide incentives, thus creating vested interests in a given institutional structure. Learning and the development of ideas and beliefs is therefore biased in accordance with the structure, cementing initial institutions. Politically, the beneficiaries of an institutional incentive structure are often able to transform their economic gains into political power, which enables them to resist institutional change (Acemoglu and Robinson 2012). In both arguments observed differences in institutional quality have deep roots and will disappear only very gradually. Curiously enough, the thesis that the impact of historical and natural circumstances is stable or at most slowly declining has rarely been tested directly. Studies claiming to study long-term persistence usually use a cross-sectional set-up, tracing current institutional and economic differences to historical or natural differences (Spoloare & Wacziarg 2013). Yet this only tells us that deep determinants matter now. What we do not know is whether the impact of deep determinants has always been this big, and whether it is stable or slowly receding, as the theoretical argument wants it. In this paper, we trace the evolution of explanatory power of deep determinants for institutional quality over time. We do so by estimating reduced form regressions of institutional indicators (taken from the Polity IV dataset) on a broad range of popular deep determinants for each year since 1850. We subsequently study the evolution of the proportion of explained variance and the standardized coefficients as indications of the impact of deep determinants and the room societies have to escape from the deterministic trend. Doing so, we find that for a wide range of historical and natural determinants proposed in the literature, the impact of natural and historical roots on comparative institutional and economic development is a fairly recent phenomenon, and that the explanatory power of deep determinants has been consistently increasing. The room for societies to escape the historical and environmental straitjacket seems to narrow. We conclude that the impact of deep determinants on development is historically contingent. Their ability to explain differences in institutional quality seems not to be universal, but to be a product of the latter half of the 20th century. For institutional theories of comparative development, our results provide something of a puzzle. Rather than having a long-term persistent effect, deep determinants have begun to substantially matter only recently. This seems to disqualify much of the literature about the intergenerational transmission of development (Spolaore & Wacziarg 2013), because it has focused on the wrong problem. The question is not what accounts for long-term persistence, but which aspects of our current economic system render deep determinants so important nowadays. More in general, the results indicate that we need to be much more aware of the historical contingency of our explanations. When nature or history matters, it is because they have been made to matter. From the perspective of policy, this is good news: where Francois and Zabonjik (2005, 51) argue that due to the impact of inherited conditions ‘late developing countries may not easily be able to transplant the modes of production that have proved useful in the West’, our results suggest that this impact of deep determinants is conditional and therefore subject to changes in the global economic system. There is a way out. The current challenge for institutional theory is to find it. In the remainder of this paper, we first review the literature about deep determinants and the intergenerational transfer of development. From this discussion, we derive the proposition that the impact of deep determinants is consistent but slowly receding over time. In section 2, we explain the data and methods used to test this proposition. Section 3 provides the results, showing that for most determinants, explanatory power is steadily increasing. We round off with a conclusion and discussion. 2. Deep determinants and the long-term persistence of development Ever since Adam Smith’s ‘The Wealth of Nations’ (1776), scholars have been debating the question why some societies have grown more prosperous than others. Traditionally, answers to this question focused on factors such as investment, population growth and technological progress. More recently, differences in governance, and economic and political institutions have been put forward as important factors (Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson 2001; Easterly and Levine 2003; Kaufmann, Kraay and Zoido-Lobatón 1999; Rodrik, Subramanian and Trebbi, 2004). By now, it has become widely accepted that differences in institutions provide a big part of the explanation for differences in development. What is less clear, however, is where these differences in institutions come from. A burgeoning new literature attempts answer this question by relating developmental differences to so-called deep determinants: differences in historical, geographical and natural conditions (e.g. Ashraf & Galor 2013; Comin, Easterly & Gong 2010; Easterly and Levine 2003; LaPorta et al 1998, 2008; Spolaore & Wacziarg 2013; Tabellini 2010). Within this literature, two main strands can be distinguished. First, a large body of research has focused on natural circumstances as explanation for differences in development. This literature assesses the impact of geographic and biological conditions such as access to waterways (Rappaport and Sachs 2003), suitability to agriculture and domestication (Diamond 1997 ; Olsson and Hibbs 2005), or disease environment (Maseland 2013; Sachs 2001; Sachs and Malaney 2002). These differences in conditions may have either a direct effect on development, burdening hot countries with lower agricultural productivity and a higher transmission of diseases for example (Sachs 2001); or an indirect effect through historical channels. An example of the latter is the famous thesis by Diamond (1997), claiming that a number of environmental advantages enjoyed by Eurasians enabled the adoption of agriculture and pastoralism sooner than elsewhere, providing Eurasia with a head start in the development of larger population centres and subsequent technological innovation (Ashraf & Galor 2011; Diamond 1997; Olsson & Hibbs 2005). Other examples include the arguments by Engerman & Sokoloff (1997, 2002), Acemoglu, Johnson & Robinson (2001), Easterly and Levine (2003) about the effects of crops and diseases on settlement of European colonizers, suggesting that differences in settlement patterns resulted in differences in institutional quality. In this perspective, initial differences in bio-geographical circumstances matter because they have set in motion divergent evolutionary paths. Second, various authors have proposed a wide range of socio-historical factors as determinants of development (e.g. Becker & Woesman 2009; Barro & McCleary 2003; Comin, Easterly & Gong 2010; Guiso, Sapienza & Zingales 2008; LaPorta, Lopez de Silanes & Shleifer 2008; Putterman & Weil 2010; Tabellini 2010). Again, determinants may either have a direct on present institutions and economic performance, or an indirect effect through affecting institutional development in the past, the effects of which still can be felt today. Guiso, Sapienza & Zingales (2003) and Noland (2005), for example, argue that present day religious denominations directly shape economic attitudes and impact economic growth. By contrast, Becker & Woesman (2009) show that any effect of Protestantism on growth runs through a historical effect on literacy rates, setting of a higher rate of human capital development that persists until today. In line with the latter argument, Guiso et al (2008) claim that differences in social capital between Italian cities reflect the impact of different experiences in medieval times. Greif and Tabellini (2010) argue that the emergence of clans in China and cities in Europe in medieval times as dominant forms of institutional enforcement set off both regions on diverging institutional trajectories. LaPorta et al (2008) claim that differences in the origin of legal systems, which to some extent reflect the borders of the former Roman empire, have a persistent effect on institutional and economic development. Not going back as far as that, Tabellini (2010) shows that differences in 19th century literacy rates and political institutions in regions of Europe still can be felt in today’s economic attitudes and outcomes. Institutional persistence Both direct and indirect arguments imply the presence of long-term institutional persistence (Acemoglu and Robinson 2008; Guiso et al 2008) in institutional development. When deep determinants affect development directly, this impact remains as long as the determinants themselves do not change. The reasons for institutional persistence in the indirect channel are more complex. Several arguments may be found in the literature. First, North (1990, 1991, 2005) argues that institutional persistence is a consequence of symbiosis between institutions and organizations, and, more importantly, interdependencies between institutions and learning. In this argument, an institutional environment provides an incentive structure to economic agents. Organizations are created to respond to these incentives. Since the investment in the creation and maintenance of such organizations would become irrelevant upon changes in institutional arrangements, agents have a strong incentive to try to maintain the status quo. In addition, both agents’ investment in knowledge development and their ability to develop new ideas and insights is shaped by pre-existing social structures. The knowledge agents seek to acquire is the type of knowledge that is most profitable given the set of existing institutional incentives (North 1991). This sets societies off on a path of technology development that is strongly intertwined with its institutional system. The most important mechanism for institutional persistence in North’s thinking, however, is the fact that any new information that we learn is filtered and shaped by our pre-existing mental models (North 1991, 2005). This implies that any information that potentially undermines our inherited cultural beliefs is likely to be rejected or re-interpreted in a way that fits within our mental models. As a result, learning will further support and cement inherited ideas, making radical change unlikely. In a similar argument, Bisin and Verdier (2000) argue that the transmission of knowledge and values from one generation to the next is determined by the decisions of parents, who interpret this decision through their own cultural perspectives. Consequentially, ideas, beliefs and values are usually subject to incremental change only. A second line of literature stresses symbiosis between institutions and political power as a cause for institutional persistence. This argument is most clearly visible in the work of Acemoglu and Robinson (Acemoglu and Robinson 2000, 2001, 2006, 2008). In this line of reasoning, a distinction is made between economic and political institutions. Economic institutions determine the distribution of profits, and their shape is a function of the distribution of interests and political power in society so that powerful groups set economic institutions to further their interests. Political power is a combination of de jure and de facto political power. De jure power stems from formal political institutions, while de facto power results from investment in lobbying and other forms of influence. In the argument of Acemoglu and Robinson (2008), the economic institutions prevalent in a society may favour some groups over others, giving them the means to invest in more de facto political power. In turn, they are likely to use this power to exert pressure to keep economic institutions as they are. A system emerges that is highly resistant to change. Even when formal political institutions change towards a more inclusive de jure system, elites respond to this by increasing their investment in de facto power and making sure that economic institutions are left intact (Acemoglu and Robinson 2008). This symbiosis between economic institutions and political power is thought to explain the long term persistence of institutional arrangements introduced in colonial times (Acemoglu Johnson and Robinson 2001). Once arrangements are in place in a society that disenfranchise large parts of the population, it is hard to change them into a more inclusive institutional system. Third, institutional persistence has been argued to be a product of interdependencies between economic institutions. This argument is most closely associated with the work of Hall and Soskice (2001), who claim that any economic institution is part of a coherent system that makes up a distinct variety of capitalism. Illustrating their argument with examples from Germany and the United States, they show that the functioning of institutional arrangements is dependent on the presence of other, complementary institutions. The pervasiveness of on the job training in the German “coordinated market economy”, for example, is dependent on the presence of collective wage bargaining institutions, as these prevent hold-up by individual workers. In the American “liberal market economy”, lacking such collective bargaining, workers invest in training themselves and focus on acquiring more general skills that make them attractive to a large range of employers, rather than on the highly specialized, firm-specific skills that are typical for the German system. Careers are advanced by switching employers in the US, which is related to higher labour market flexibility (Hall and Soskice 2001). Institutional complementarities such as these imply that profound institutional change is unlikely. Reforming one institution in isolation is not effective since its functioning depends on its position in the entire institutional setting. What is more, different institutional arrangements give rise to different comparative institutional advantages, making sure that different industries and interests arise under different varieties of capitalism. Not only the ability to change institutions, but also the incentive to change is reduced as a result. Much like in the argument about economic and political institutions of Acemoglu and Robinson (2006, 2008), interdependencies among institutions result in a lock-in effect leading to long-term institutional persistence. Their differences notwithstanding, all these arguments maintain that deep determinants should have a long-term, persistent effect on economic and institutional development. In general, empirical support for this argument has come from cross-sectional studies, showing that deep determinants affect economic performance and institutional quality today (e.g. Acemoglu, Johnson & Robinson 2001; Ashraf & Galor 2011, 2013; Becker & Woesman 2009; Comin, Easterly & Gong 2010; , Easterly and Levine 2003; Engerman & Sokoloff 1997, 2002; Guiso, Sapienza & Zingales 2008; LaPorta, Lopez de Silanes & Shleifer 2008; Olsson & Hibbs 2005; Putterman & Weil 2010; Tabellini 2010). Results such as these are seen as evidence of a long-term, intergenerational transmission of development (Spolaore and Wacziarg 2013). History lingers in the institutional legacy of societies. However, the fact that deep determinants make their presence felt today does not necessarily mean that they have done so in the past. Cross-sectional results in a single period cannot prove institutional persistence by themselves. A required additional assumption is that any effect of a natural or historical determinant that is found today is a remnant of an effect that was equally strong or even stronger initially and has been present ever since. More specifically, if we take the distinction between direct and indirect channels through which deep determinants matter into account, we expect that direct effects of deep determinants are stable over time, while indirect effects—i.e. effects through historical legacies—slowly wear off over time. In other words, Hypothesis 1: The effect of deep determinants directly affecting contemporary economic performance is stable over time. Hypothesis 2: The effect of deep determinants directly affecting contemporary institutional quality is stable over time. Hypothesis 3: The effect of deep determinants affecting economic performance through their historical legacy is slowly decreasing over time. Hypothesis 4: The effect of deep determinants affecting institutional quality through their historical legacy is slowly decreasing over time. Data & Methodology In order to test these hypotheses, we follow a simple methodology that consists of two steps. First, we use a broad set of ´deep determinants´ that have been proposed in some of the most prominent studies in economics and relate these to measures of institutional quality and economic performance one by one. We run separate regressions for each year in our study, varying the dependent variable but leaving the presumably time-invariant deep determinants constant. Doing so, we save the r-squares of the regression and the standardized coefficients of the deep determinants. We interpret the coefficients as a measure of explanatory power of the deep determinant and the r-squares as indicators of the potential for countries to dodge the deep-determined trend. In a second step, we assess whether these r-squares and standardized coefficients are stable over time, decreasing or increasing. In order to ensure comparability across years, we restrict our sample of countries to those that have observations for all years in the period under study. In our main analysis, we investigate the period 1965-2012, which allows us to include most former colonies in the investigation, maximizing the scope of the investigation. In a second analysis, we focus on the period 1850-2012, which allows us to look at longer time trends but only for the small sample of countries that already existed by 1850. Table A1 in the appendix provides the lists of countries included in both samples. Dependent variables In order to measure institutional quality we use the indicator of constraints on the executive taken from Polity IV. This measure has been used as a proxy for property rights protection and shown to be capturing the most important element of institutional quality (Acemoglu, Johnson & Robinson 2001; Acemoglu & Johnson 2005). The index runs from 1 to 7, with a score of 1 reflecting unlimited executive authority and a score of 7 executive parity of subordination. Yearly interpolation has been used to predict values in years of political upheaval. A potential problem of this variable is that it is truncated at the low and high ends. For our specific purposes, a concern may be that in case of a general trend towards more executive subordination, the explanatory power of any determinant will decrease over time because the countries with the ‘highest’ institutional quality are not able to rise further due to scale limits, while the others are catching up. We normalize the index for each year to reduce the problem, but it remains a potential concern. Our second dependent variable is economic performance, measured by the log of income per capita levels taken from the World Development Indicators. Bio-geographical determinants We first explore a set of natural and geographical conditions proposed in the literature as deep determinants of development. A first indicator is the access to waterways, measured as the average distance of a country to the nearest sea-navigable river or ice-free coastline in thousands of km (Gallup, Sachs and Mellinger 1999). Better access to waterways is thought facilitate the diffusion of technology between centres of population. Similarly, Diamond (1997) argues that the orientation of the continental axis determines the transmission of climate-dependent technology between societies. To capture this effect, we include the ratio of the largest longitudinal distance to the largest latitudinal distance of a continent (Olsson and Hibbs 2005). Ashraf and Galor (2013) argue that genetic diversity affects the levels of trust and innovativeness of society, affecting long run technological development and growth. We include their measure of genetic diversity (adjusted to population) to study this effect. We also explore a number of variables related to the suitability for agriculture and pastoralism. A measure of rainfall is taken from Ashraf and Galor (2013). This indicator reflects the average monthly precipitation between 1961 and 1990, and is based on Nordhaus (2006) and New et al (2002). A measure of the number of pre-historically available domesticable plants and animals is taken from Olsson and Hibbs (2005). We include the percentage of arable land in a country (World Development Indicators) and measures of soil fertility and the suitability of land for agriculture (Michalopoulos 2011, based on Ramankutty et al 2002). To capture the effect of climatic conditions on productivity and proneness to diseases, we use a measure of the share of the population living in temperate zones (Gallup, Sachs and Mellinger 1999), the average monthly temperature (Ashraf and Galor 2013; Nordhaus 2006), climatic suitability for agriculture (Olsson and Hibbs 2005), absolute latitude, and the percentage of the population at risk of contracting malaria (Ashraf and Galor 2013; Gallup and Sachs 2001). Socio-Historical determinants In addition to the set of bio-geographical determinants, we explore the temporal consistency of a number of historical variables. Several authors have argued that differences in the level of technology and development arising early on in history continue to affect development today (Ashraf and Galor 2011; Comin, Easterley and Gong 2010; Putterman and Weil 2010). Variables attesting to such an effect are a measure of the years passed since the Neolithic revolution took place for a population, and the distance to the technological frontier in year 1AD (Ashraf and Galor 2013). Following up on the claim of Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson (2001) that differences in settler mortality affected settlement patterns of colonies and subsequent institutional and economic development, we include their measure of settler mortality and the share of the population of European descent in 1900 (Acemoglu, Johnson & Robinson 2001). Legal origin dummies are taken from La Porta et al. (1999). From this dataset, we also obtain a measure of the shares of the population affiliated with major world religions. Finally, we include the ethnic fractionalisation index constructed by Alesina et al (2003). Results In our first set of analyses, we look at the impact of deep determinants on differences in economic performance. To start, we look at biogeographical conditions which are more closely related to direct effects. Figure 1a present the temporal trends in absolute standardized coefficients (left) and r-squares (right) and for various bio-geographical determinants. <<Insert Figure 1 about here>> A first observation is that the effect of determinants do not appear to be robust over time. Effect sizes and explained variance vary substantially between periods. For some determinants, such as genetic diversity, the r-square is zero for a large part of the period under investigation, indicating that when research into the effects of ruggedness (e.g. Nunn & Puga 2007)had been done in the 1970s, it would not have generated any significant results. Second, results generally indicate an increasing trend in both the proportion of variance explained by deep determinants and their explanatory power. Increases are often quite substantial. For genetic diversity and terrain ruggedness, for example, the standardized coefficient more than quadruples in size over the given period. Figure 1b presents the same information for determinants more associated with indirect, historical legacy effects. Results give rise to the same conclusions, although there is somewhat more variation. Effect sizes and explanatory power are generally inconsistent over time and seem to be subject to an increasing trend. Early technology and settlement patterns also portray increasing effect sizes, but inconsistent r-squares. The effects of Protestantism and Catholicism are the true exceptions. While also not being robust over time, the effect of these religions seems to rapidly decline, even when the negative impact of Islam increases. Figure 2 presents the same exercise, but with institutional quality as dependent variable. Section 2a presents the results for biogeographical determinants, and 2b the results for socio-historical factors. Again, we find increases in both effect size and the proportion of variance explained across the board. Effects are again somewhat less pronounced and consistent for historical legacy determinants. The impacts of some determinants, such as settler mortality, the availability of domesticable animals and legal origin seem to become smaller after peaking earlier. While this only adds to the picture of intertemporal inconsistency, they dodge the general trend of increases in effect size and explanatory power. Overall, increases are the rule and they are often even more substantial than in the case of income. The effect of soil fertility, for example, increases by a factor 6 between 1960 and 2012, and the explained variance of this variable alone grows from close to zero to almost 20%. For the proportion of arable land, the effect size even rises ten-fold. <<Insert Figure 2 about here>> To see whether the increases over time are statistically significant, Tables 1 and 2 present regression results for both r-squares and absolute standardized coefficients on year, for institutional quality and income respectively. The first column shows the regression coefficient of the first-step standardized coefficients regressed on time, and the associated t-statistic. The second column does the same for the regression of r-squares on time. The third column provides the percentage of years in which the effect of the determinant on economic performance is statistically significant (to be added). These more formal tests confirm the general picture emerging from Figures 1 and 2. For most determinants, both effect sizes and the proportion of variance explained significantly increases over time. As a result, a large portion of the determinants do not seem to be robustly significant. This does not mean that deep determinants do not matter, but it does indicate that their effect is contingent on the conditions as they have existed in the global economy for the past decades. Apparently, most determinants have become important only recently and are becoming increasingly dominant. Conclusion & discussion In this paper, we have taken to the test the implicit argument in the literature about deep determinants of growth that any effect of deep determinants today is a remnant of such effects in the past. By re-regressing measures of economic performance and institutional quality on a large number of deep determinants for various years since 1850, we have shown that the effect of deep determinants is far from robust to changes in the year of measurement of the dependent variables. More strikingly, we show that for most determinants proposed in the literature, a consistent upward trend in both effect size and proportion of variance explained exists. In contrast to what one theoretically would expect, the effect of natural circumstances or historical events is not wearing off, but is increasing. In fact, for many determinants, no significant effects on institutions or economic outcomes would have been found had research been done a few decades earlier. What to make of this? To be sure, this analysis does not invalidate the literature into the deep determinants of growth and institutional development. Rather, it confirms that the effect of deep determinants is real, but that it is something recent instead of long-standing. This compels us to look again more at the present rather than the past in order to understand current differences in economic and institutional performance. Rather than further expanding the list of deep determinants of development, our research should focus on explaining what it is in the current economic system that has made deep determinants suddenly so prominent. If we are able to answer that question, we can also begin to understand what countries with less fortunate natural and historical legacies may do to escape from their pre-‘determined’ path of development. Instead of focusing on the historical and natural factors that are holding some societies back, institutional economics may focus on what may be done to reduce their effect. From the perspective of economic growth policies, it is not the pre-determined trend that matters. It is the capacity to deviate from this trend. References (to be updated) Acemoglu, Daron and James A. Robinson 2012. Why Nations Fail. New York: Crown Publishers. Acemoglu, Daron, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson . 2005. “Institutions as a Fundamental Cause of Long-Run Growth.” In Handbook of Economic Growth, Volume 1A, edited by Philippe Aghion and Steven N. urlauf, 385–472. Amsterdam and Boston: Elsevier, North-Holland. Acemoglu, Daron, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson. 2001. The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development: An Empirical Investigation. American Economic Review 91:5, 1369–1401. Dell, Melissa. 2010. The persistent effects of Peru’s mining Mita. Econometrica, 78(6) 1863–1903. Easterly, William & Levine, Ross, 2003. Tropics, germs, and crops: how endowments influence economic development. Journal of Monetary Economics, 50(1), 3-39. Haber, Stephen and Menaldo, Victor A. 2011. Rainfall, Human Capital, and Democracy. Available at SSRN: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1667332. LaPorta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F. & Shleifer, A. 2008. “The economic consequences of legal origin,” Journal of Economic Literature, 46.2: 285–332. North, D. 1991. Institutions. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5:1, 97-112 North, D. 2005. Understanding the process of economic change, Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp 11-80. North, Douglass. 1990. Institutions, Institutional Change, and Economic Performance. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Nunn N. 2008. The Long Term Effects of Africa's Slave Trades. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 123(1):139-176. Sokoloff, Kenneth L., and Stanley L. Engerman 2000. History Lessons: Institutions, Factor Endowments, and Paths of Development in the New World. Journal of Economic Perspectives 14:3, 217–232. Spolaore, Enrico, and Romain Wacziarg. 2013. How Deep are the Roots of Economic Development? Journal of Economic Literature 51(2), 325–36. Tabellini, Guido. 2008. Culture and institutions: economic development in the regions of Europe. Journal of the European Economic Association 8 (4): 677-716. Figure 1a The temporal stability of the effect of natural determinants on income Absolute Latitude Genetic diversity .08 1000 .42 1990 2000 2010 1960 1970 1980 year 1990 2000 2010 .04 1960 1970 1980 year Ruggedness 2000 2010 Soil suitability 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2000 2010 2000 2010 Soil Suitability .02 .6 R-Square .01 .2 0 1980 1990 2000 2010 .005 .3 0 .005 .4 beta .01 R-Square .5 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 1980 1990 year Suitability for agriculture Suitability for Agriculture Temperature Temperature .38 .36 -.08 .32 R-Square beta -.07 .0015 .001 1980 1990 year 2000 2010 1960 1970 1980 1990 year 2000 2010 .28 0 -.09 .3 .0005 0 R-Square .02 .002 .04 .0025 -.06 year -.02 1970 1970 year -.04 1960 1960 year .34 beta -.5 1970 .06 1960 beta 1960 year .5 1 .015 Ruggedness 1990 year .025 1980 .015 1970 .02 200 .34 1960 .06 R-Square 800 beta 600 .035 400 .36 .38 rsqrlat_abst .4 .045 beta .04 Genetic Diversity .1 Absolute latitude 1960 1970 1980 1990 year 2000 2010 1960 1970 1980 1990 year Distance to waterways .22 .16 1.2 .14 1 .5 .4 .6 .42 .18 .2 R-Square 1.6 beta 1.4 .44 R-Square .7 beta .46 .8 .24 Distance to waterways 1.8 Climate .48 Climate 1980 1990 2000 2010 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 year year year year Malaria Malaria Population in temperate zones Population in temperate zones 2 .42 .44 R-Square 1.8 1960 1970 1980 1990 year 2000 2010 1960 1970 1980 1990 year 2000 2010 .38 .4 1.4 -2.2 .4 1.6 beta .5 .45 -2 beta -1.8 R-Square .46 -1.6 2010 .48 1970 .55 1960 1960 1970 1980 1990 year 2000 2010 1960 1970 1980 1990 year 2000 2010 Figure 1b The temporal stability of the effect of historical legacies on income 1980 1990 2000 2010 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 .01 R-Square 1980 1990 2000 2010 1980 1990 Protestantism 1990 Catholicism Catholicism 2000 1960 1980 1990 2000 .2 1970 1980 1990 year 1980 2000 2010 1990 .4 .18 beta .3 .25 .14 .2 .1 1960 1970 Domesticable animals .12 .08 2010 1960 Domesticable animals .06 2000 .14 2010 year .1 R-Square 1970 year .12 beta .0095 .009 1990 year 2010 .16 2010 .14 year 1980 2000 .12 1980 .45 1970 .08 .016 1960 .35 2010 year R-Square 2000 2010 .1 .017 .07 .06 1990 R-Square .019 .08 .018 beta .09 R-Square .1 -.009 beta -.01 -.011 -.012 1980 2000 .18 Protestantism .02 Islam .11 Islam .0085 1970 1970 year .008 1960 1960 year -.013 1970 1970 year .01 1960 0 1960 year .16 1970 -.008 1960 -.3 .8 .1 1 -.2 .005 .15 -.1 beta .2 R-Square 1.2 1.4 beta 0 1.6 .25 Civil law .015 Civil Law .1 Time since neolithic revolution 1.8 Time since neolithic revolution 1960 1970 1980 1990 year 2000 2010 1960 1970 1980 1990 year 2000 2010 European settlers 1900 R-Square beta .54 .019 .3 1980 1990 2000 2010 .5 .52 .018 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 year year year year Settler mortality Settler mortality Distance to technological frontier 1AD Distance to technological frontier 1AD 1960 1970 1980 1990 year 2000 2010 -.26 -.65 .35 .06 -.6 -.24 .4 .07 .08 R-Square -.2 beta -.22 .45 -.55 -.5 R-Square .5 -.18 -.4 -.45 2010 .09 1970 .55 1960 beta .017 .2 -3 .25 -2.5 R-Square .56 .58 .021 .02 .35 -2 beta European settlers 1900 .6 Ethnic fractionalization .4 -1.5 Ethnic fractionalization 1960 1970 1980 1990 year 2000 2010 1960 1970 1980 1990 year 2000 2010 1960 1970 1980 1990 year 2000 2010 Figure 2a The temporal stability of the effect of natural determinants on institutional quality Genetic diversity Genetic diversity .06 Absolute latitude .04 R-Square 0 beta .1 1980 1990 2000 2010 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 year year year year Malaria Malaria Population in temperate zones Population in temperate zones 1980 1990 2000 2010 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 .1 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 1960 1970 1980 1990 year year year year Distance to waterways Distance to waterways Climate Climate 2010 2000 2010 1960 1970 1980 1990 year 2000 2010 .25 .15 .2 R-Square .4 beta .35 1960 1970 1980 1990 year 2000 2010 .1 .05 1 .1 .25 .3 1.1 .15 1.2 R-Square .2 beta 1.3 .45 .25 .5 2000 .3 1970 1.4 1960 .8 .1 -1.6 .15 .2 -1.4 1 .2 .25 R-Square 1.2 beta .3 beta -1.2 R-Square .4 -1 .3 -.8 2010 1.4 1970 .5 1960 0 0 -15 .2 -10 .05 .02 -5 .3 R-Square beta .4 .15 5 .2 .5 10 Absolute latitude 1960 1970 1980 1990 year 2000 2010 1960 1970 1980 1990 year Suitability for argiculture .4 1980 1990 2000 2010 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 1960 1970 1980 1990 year year Soil fertility Soil fertility Ruggedness Ruggedness 2 2000 2010 2000 2010 .04 .06 1.5 1 beta 2010 .5 .1 R-Square 1 .15 1.2 .8 2000 .08 year 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 1960 1970 1980 year 1990 2000 0 -.5 0 .2 0 .4 .05 .02 .6 beta 1960 year R-Square 1970 .2 1960 0 0 -.06 .1 .1 .15 .05 .2 .1 beta R-Square .3 .25 .2 R-Square -.04 beta -.05 Suitability for agriculture .15 Temperature .3 -.03 Temperature 2010 1960 1970 1980 year 1990 2000 2010 1960 1970 1980 1990 year year Civil law Civil law Figure 2b The temporal stability of the effect of historical legacies on institutional quality .08 Time since neolithic revolution R-Square .04 .05 -.2 beta R-Square .6 -.4 .02 .4 1960 1970 1980 1990 year 2000 2010 1960 1970 1980 1990 year 2000 2010 0 -.6 0 0 .2 beta 0 .06 .8 .1 1 .2 Time since neolithic revolution 1960 1970 1980 1990 year 2000 2010 1960 1970 1980 1990 year Catholicism Catholicism 1980 1990 2000 2010 .1 R-Square beta .006 .05 .004 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 1960 1970 1980 1990 year Islam Islam Ethnic fractionalization Ethnic fractionalization -1 1970 1980 1990 European descent 1900 European descent 1900 2000 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 .15 2010 1960 1980 Settler mortality Settler mortality R-Square -.3 beta .4 .5 1990 year 1960 1970 1980 1990 year 2000 2010 .2 1960 1970 1980 1990 year 2000 2010 .1 -.5 .1 .008 .2 .01 -.4 .3 R-Square 1970 year .4 .014 beta 2010 .1 2010 -.2 year .012 2000 .05 -2 1960 .5 2010 year .3 2000 .2 -1.2 beta -1.4 -1.8 .1 .05 1990 2010 -1.6 .15 .2 R-Square .25 -.008 beta -.01 -.012 -.014 1980 2000 .25 year .3 year -.016 1970 .016 1960 0 1960 year R-Square 1970 -.006 1960 0 .05 .012 .002 .014 .1 .016 beta R-Square .018 .15 .008 .02 .01 .15 Protestantism .2 .022 Protestantism 1960 1970 1980 1990 year 2000 2010 1960 1970 1980 1990 year 2000 2010 Technology in 1AD .025 .02 R-Square 0 beta 1960 1970 1980 1990 year 2000 2010 1960 1970 1980 1990 year 2000 2010 0 -.15 .1 .005 -.1 .15 .01 -.05 .015 .3 .25 .2 R-Square .12 .1 .08 .06 beta Technology in 1AD .05 Domesticable animals .14 Domestiable animals 1960 1970 1980 1990 year 2000 2010 1960 1970 1980 1990 year 2000 2010 Table 1 Temporal stability of effects of deep determinants on institutional quality Latitude Neolithic Malaria Access to waterways Ruggedness Soil Suitability for agriculture Islam Catholicism Protestantism Climate Technology 1AD Settler Mortality European settlers 1900 Temperature Population in temperate zone Ethnic fractionalization Civil law Beta (absolute) .004* (7.28) 7.25e-3* (5.50) .011*(8.09) .004*(6.77) .030*(9.25) .020*(20.2) .006*(17.0) 1.56e-4* (9.97) 2.03e-4*(13.0) -1.67e-4* (9.6) .002*(6.94) .002*(7.64) .003* (4.55) 9.22e-5*(7.31) 1.90e-4* (3.38) .006*(5.81) .009*(4.96) .018*(10.3) R-square .003* (12.1) 7.29e-4* (5.27) .005* (11.39) .002*(9.26) 6.82e-3*(8.57) .004*(21.9) .003*(18.0) .004* (12.45) .003*(13.6) -.002*(8.34) .003*(13.5) 4.44e-3*(15.2) -.003* (3.79) .005*(12.0) .002*(5.84) .003*(11.0) .002*(7.51) -.003*(10.3) Table 2 Temporal stability of the effects of deep determinants on income Latitude Neolithic Malaria Access to waterways Ruggedness Soil Suitability for agriculture Islam Catholicism Protestantism Climate Technology 1AD Settler Mortality European settlers 1900 Temperature Population in temperate zone Ethnic fractionalization Civil law Beta (absolute) 2.17* (19.5) .018* (53.4) .011*(8.09) .013*(21.8) .027*(36.6) .006*(12.8) 1.48e-3*(9.44) 9.46e-4* (22.6) -2.03e-4*(6.59) -2.68e-5* (3.97) .005*(17.8) 8.11e-4*(4.70) .005* (33.7) 6.05e-5*(12.8) 4.78e-4* (26.3) .010*(15.4) .025*(31.8) .006*(12.5) R-square 9.04* (7.64) .003* (61.0) .005* (11.39) .002*(21.5) 2.71e-3*(16.5) 2.85*(8.14) 3.96e-5*(8.24) 8.52e-4* (9.96) -.001*(37.0) -.001*(18.6) .001*(12.8) -7.82e-5*(1.04) .004* (26.6) -.001*(7.12) .001*(14.4) .002*(14.7) .004*(73.5) 1.79e-4*(7.26)