tpj12541-sup-0016-Legends

advertisement

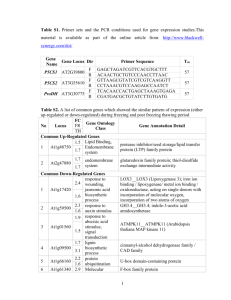

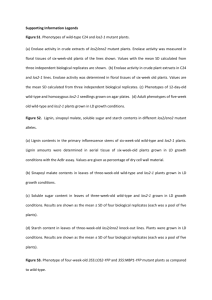

FULL SUPPORTING INFORMATION Legends for Supporting Figures Figure S1. SDS-PAGE analysis of purified (His)6-UGT74 enzymes. Recombinant (His)6-tagged UGT74 proteins were expressed in E. coli and affinity purified as described in Experimental Procedures. Figure S2. Expression analysis of UGT74 genes by qRT-PCR in ugt74b1-1 plants and other ugt74 T-DNA insertion lines. (a) Expression of UGT74 genes in ugt74b1-1 plants relative to their expression in the Ws-0 wild-type (100%). UGT74E1 transcript levels were below the detection limits. None of the apparent differences is significant by Student’s t-test. (b) Expression of UGT74 genes in the T-DNA insertion lines used in this study. In each case, the expression of the cognate gene in the T-DNA line is normalized to expression of the same gene in the appropriate wild-type (Ws-0 for ugt74f1; Col-0 for all others). We were unable to detect expression of UGT74E1 in plants grown under normal conditions; a 4-hour treatment with H2O2 induced expression of this gene in wild-type, but not in the ugt74e1-2 mutant, and values for this experiment are reported in this figure. Expression of UGT74F2 in line ugt74f2-i1a was not measured; this mutant produces a misspliced mRNA, and was previously shown to be a knockout (Quiel and Bender, 2003). Figure S3. Adventitious root formation. We previously showed that the ugt74b1-1 mutant develops substantially more adventitious roots than the wild-type when grown under conditions that promote adventitious rooting (Grubb et al., 2004). This is also true for the ugt74b1-2 line, but is not further augmented by additional loss of UGT74C1 in ugt74b1-2 ugt74c1-2 seedlings. In this representative experiment, hypocotyls of ugt74c1-2 (left) and sur1 (right) seedlings produced no and excessive adventitious roots, respectively. Figure S4. Glucosinolate levels in various organs of the ugt74c1-2 single mutant. Values shown are totals of all detected aliphatic (Met) or indolic (Trp) compounds, expressed relative to wild-type content (1 = 100%); error bars represent standard error. “Flowers” indicates open flowers harvested prior to pistil expansion. “Siliques” indicates fully expanded, but still green, fruits. None of the differences are significant by Student’s t-test. Figure S5. Quantification of 35S::UGT74C1 and 35S::UGT74B1 expression in transgenic ugt74b1-2 lines by qRT-PCR. (a) Line C1-6.17.6 highly overexpresses UGT74C1 mRNA levels relative to the Col-0 wildtype (~200-fold). (b) Line C1-2.10.8 shows significantly decreased UGT74C1 transcript levels, likely due to gene silencing. (c-i) Additional 35S::UGT74C1(ugt74b1-2) lines with variable levels of UGT74C1 transcripts. Asterices (*) indicate significant differences (p < 0.05, Student’s t-test) with respect to the wild-type. 1 Figure S6. Uncollapsed version of the phylogenetic tree depicted in Figure 9. The number next to each sequence is the gi number of the source file retrieved from Genbank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez). Figure S7. Relative expression of UGT74 genes in wild-type plants. No signal was detected for UGT74E1 in any of the experiments described below. (a) Values for the wild-type plants that were used to generate Figure S2. Signals are scaled to UGT74F1. Although UGT74B1 was not measured in this experiment, the very strong correlation with the datasets presented in lower two panels suggests its expression level is similar to UGT74C1. (b) Expression values from the wild-type samples of a microarray experiment conducted in house as a part of an unrelated project. Raw data for each chip were normalized to the expression for PP2A, as in the qRT-PCR experiment. (c) Absolute expression values for the vegetative rosette dataset from the Arabidopsis eFP Browser (http://bar.utoronto.ca/efp/cgi-bin/efpWeb.cgi). Legends for Supporting Tables Table S1. Screen of purified recombinant Arabidopsis Family 1 UGT~GST fusion proteins for activity toward phenylacetothiohydroximate (PATH). Affinity-purified proteins were assayed as described in Experimental Procedures. For each pH condition, the activities of UGT~GST protein fusions toward PATH are given relative to UGT74B1~GST, the most active recombinant UGT enzyme. Assignment of enzymes to groups is according to (Li et al., 2001). Table S2. Hormone content of single and double ugt74c1-2 and ugt74b1-2 mutants in comparison with Col-0 wild-type (3 weeks old). OPDA (12-oxo-phytodienoic acid), ACC (1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate), IAA (indole-3-acetic acid). Measurements of jasmonic acid, jasmonate-isoleucine, indole-3-butyric acid, and abscisic acid were below the detection limits. Significant differences relative to Col-0 (p <0.05) are indicated (*). Table S3. Correlation values for UGT74 and glucosinolate pathway gene expression. Table S4. Details of ugt74 knockout lines studied. Table S5. Details of plasmid construction for heterologous expression of UGT74 members. Table S6. Primers for validation of ugt74 T-DNA insertion lines by qRT-PCR. Table S7. The alignment used to generate the UGT74 phylogenetic trees depicted in Figure 9 and Figure S6. 2 Supporting Methods Method S1. Construction of transgenic Arabidopsis lines Construction of transgenic Arabidopsis lines relied on the GATEWAY system (Invitrogen). Cloning cassettes from the pQE30-based expression constructs described above were amplified with primers 5’- GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTCTATGAGAGGATCGCATCACC-3’ and 5’- GGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGTACAGGAGTCCAAGCTCA-3’, which introduced recombination sites attP1 and attP2, allowing for recombination into the pDONR221 vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) via Gateway Clonase II BP. The fidelity of the entry clones was checked by sequencing using standard M13 forward and reverse primers. The destination clone was created by recombination of linearized pDONR221 plasmid into pGWB2 or pGWB6 (Tsuyoshi Nakagawa, Research Institute of Molecular Genetics, Shimane University, Matsue 690, Japan) with the use of Gateway Clonase II LR. Destination vectors placed the UGTs under the control of CaMV 35S promoter and provided kanamycin resistance. While pGWB2 vector was designed to produce the His-tagged construct, pGWB6 also provided a C-terminal GFP protein tag. The destination vectors were transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 and used to transform heterozygous ugt74b1-2 plants, allowing isolation of each overexpression insertion event in both wild-type and the ugt74b1-2 backgrounds. Plants were transformed by the floral dip method (Clough and Bent, 1998). Seeds collected from primary transformants were re-screened in the T2 generation to identify lines harboring single insertions, and progeny of individual T2 plants were screened on both kanamycin and Basta to determine the genotype (homozygous or heterozygous) of the T2 parent with respect to the overexpression construct (KanR) and the ugt74b1-2 insertion (Bar). Method S2. Plant growth conditions Soil grown plants were planted in Pro-Mix ‘BX’ (Premier Horticulture, Red Hill, PA, USA) at 22°C and 70% relative humidity under illumination with fluorescent and incandescent light (16 h per day) at a photon fluence rate of approximately 120 mol m-2 sec-1. Plants were watered 2-3 times per week and fertilized with macronutrients (7.5 mM N, 1.7 mM P, 3 mM K, 3 mM Ca, and 1.2 mM Mg). For plant growth in sterile conditions, seeds were surfacesterilized for 10 min in 1.5% (w/v) sodium hypochlorite and placed on solid medium containing 8 g l-1 phytagar, 30 g l-1 sucrose, 2.15 g l-1 (0.5 ×) Murashige-Skoog (MS) salts, pH 5.6, and 1 × MS vitamin mix (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). After 2-3 days of stratification at 4oC, plants were grown at 24oC at a photon fluence rate of approximately 160 mol m-2 sec-1 for 18 h (long days) or 8 h (short days) per day. For selection of transgenic plants, the agar medium was supplemented with 25 μg ml-1 kanamycin (Sigma), or with 5.25 g ml-1 sulfadiazine (Sigma), or seedlings grown in soil were sprayed with 1% (v/v) Basta herbicide (Finale, Farnam Companies, Phonix, AZ, USA). Method S3. Analysis of endogenous hormone contents Fresh plant material (10-80 mg) was homogenized with 5 ml methanol and 50 ng each of (D4)ACC (1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid), (2H5)JA (jasmonic acid), (2H5)OPDA (12-oxo-phytodienoic acid), (-)JA-(2H3)Leu (jasmonate-isoleucine), (D6)ABA (abscisic acid), (13C6)IAA (indolyl-3-acetic acid) and [13C6, 15N1]IBA (indolyl-3-butyric acid) were added as internal standards. Extract preparation, derivatization and GC-MS analysis (Polaris Q, Thermo-Finnigan, Bremen, Germany) were performed as previously described (Grubb et al., 2004; Miersch et al., 2008; Sreenivasulu at al., 2010). 3 Method S4. Phylogenetic analysis of the UGT74 clade A search for proteins related to the UGT74 clade employed blastp searches at the NCBI website (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) with default parameters, except the organism field was restricted to green plants (taxid:33090). The following proteins were used as query sequences: UGT74B1, UGT74C1, UGT74D1, UGT74E1, UGT74F1 and UGT75C1. The latter was included because a previous phylogenetic analysis of Arabidopsis Family 1 UGTs indicated that it is closely related to, but outside of, the UGT74 clade (Li et al., 2001). An “E value” of 1 x 10-78 was chosen as the cutoff; this was the least stringent value for which every query recovered at least one sequence each from the genomes of Zea mays, Oryza sativa and Sorghum bicolor. The recovered gene lists were combined, duplicates discarded and a total of 269 records retrieved. One sequence we believe to be misannotated (UGT74E1) was corrected in both A. thaliana and A. lyrata. An initial tree was constructed, and the position of UGT75C1 was used to make a final determination of which sequences to include in further analyses. Finally, UGT74 homologs from Carica papaya were retrieved from PLAZA (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/plaza_v1/; Proost et al., 2009) and added to the alignment. For construction of the final tree, all identified protein sequences were aligned (Table S7) using the L-INS-i option in MAFFT (Katoh et al., 2005) and edited manually. The JTT+G model was selected as the best fitting amino acid substitution model according to the Bayesian Information Criterion in ProtTest (Darriba et al., 2011). To reconstruct the phylogeny we used MrBayes 3.1 (Ronquist and Huelsenbeck, 2003) as implemented at the CIPRES portal (Miller et al. 2010) and initiated two runs of eight Markov-chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) chains of 106 generations each from a random starting tree, sampling every 100 generations (additional settings: Rates = gamma, Ngammacat = 4, Aamodelpr = JTT, Temp = 0.01). A suitable burn-in was chosen based on Tracer outputs (v. 1.5; http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/tracer/ ) and convergence was assessed by standard deviation of split frequencies (< 0.08) and with AWTY (Nylander et al., 2008) by comparing the estimated posterior distributions of branch support from the two independent MCMC runs. The phylogenetic tree was rooted between the monocot and the eudicot sequences and visualized with the MEGA Tree Explorer (Tamura et al., 2011). Method S5. Comparison of relative UGT74 gene expression Methods for qRT-PCR experiments are described Experimental Procedures. Microarray gene expression analysis was conducted by the UC Berkeley Functional Genomics Laboratory Affymetrix Genechip Core Facility, utilizing the Affymetrix ATH1-121501 gene chip. mRNA was prepared from 2-week-old vegetative rosettes of wild-type (Col-0) plants according to their recommended protocol (http://qb3.berkeley.edu/qb3/fgl/microarray.cfm). Plants were frown asceptically according to our standard protocol for measuring glucosinolates (see Experimental Procedures). Data were downloaded for the “vegetative rosette” samples of the “Developmental Map” dataset at http://bar.utoronto.ca/efp/cgibin/efpWeb.cgi. This dataset was originally published by Schmid et al. (2005). Absolute expression values are shown. 4 Supporting References Clough, S.J. and Bent A.F. (1998) Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacteriummediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plan J., 6, 735-743. Darriba, D., Taboada, G.L., Doallo, R. and Posada, D. (2011) ProtTest 3: fast selection of best-fit models of protein evolution. Bioinformatics, 27, 1164-1165. Grubb, C.D., Zipp, B.J., Ludwig-Müller, J., Masuno, M.N., Molinski, T.F. and Abel, S. (2004) Arabidopsis glucosyltransferase UGT74B1 functions in glucosinolate biosynthesis and auxin homeostasis. Plant J., 40, 893-908. Katoh, K., Kuma, K., Toh, H. and Miyata, T. (2005) MAFFT version 5: improvement in accuracy of multiple sequence alignment. Nucleic Acids Res., 33, 511-518. Li, Y., Baldauf, S., Lim, E.K. and Bowles, D.J. (2001) Phylogenetic analysis of the UDPglycosyltransferase multigene family of Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 4338-4343. Miersch, O., Neumerkel, J., Dippe, M., Stenzel, I. And Wasternack, C. (2008) Hydroxylated jasmonates are commonly occurring metabolites of jasmonic acid and contribute to a partial switch-off in jasmonate signaling. New Phytol., 177, 114-127. Miller, M., Pfeiffer, W. and Schwartz, T. (2010) Creating the CIPRES Science Gateway for inference of large phylogenetic trees. In Gateway Computing Environments Workshop (GCE), pp. 1-8. Nylander, J.A., Wilgenbusch, J.C., Warren, D.L. and Swofford, D.L. (2008) AWTY (are we there yet?): a system for graphical exploration of MCMC convergence in Bayesian phylogenetics. Bioinformatics, 24, 581-583. Proost, S., Van Bel, M., Sterck, L., Billiau, K., Van Parys, T., Van de Peer, Y. and Vanepoele, K. (2009) PLAZA: a comparative genomics resource to study gene and genome evolution in plants. Plant Cell, 12, 3718-3731. Quiel, J.A. and Bender, J. (2003) Glucose conjugation of anthranilate by the Arabidopsis UGT74F2 glucosyltransferase is required for tryptophan mutant blue fluorescence. J. Biol. Chem., 278, 6275-6281. Ronquist, F. and Huelsenbeck, J.P. (2003) MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics, 19, 1572-1574. Schmid, M., Davison, T. S., Henz, S. R., Pape, U. J., Demar, M., Vingron, M., Scholkopf, B., Weigel, D., and Lohmann, J. U. (2005) A gene expression map of Arabidopsis thaliana development. Nat Genet 37, 501-506 Sreenivasulu, N., Radchuk, V., Alawasy, A., Borisjuk, L., Weier, D., Staroske, N., Fuchs, J., Miersch, O., Strickert, M. Usadel, B., Wobus, U., Grimm, B., Weber, H. And Weschke, W. De-regulation of absisic acid contents causes abnormal endosperm development in the barley mutant seg8. Plant J., 64, 589-603. Tamura, K., Peterson, D., Peterson, N., Stecher, G., Nei, M. and Kumar, S. (2011) MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol., 28, 27312739. 5