Family ecology, maternal depression, and coercion in early childhood.

advertisement

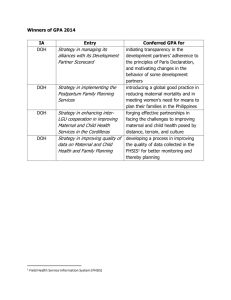

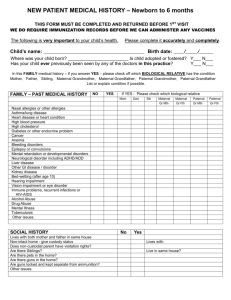

RUNNING HEAD: EFFECT OF MATERNAL DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS ON CHILD INTERNALIZING 1 Abstract Objective: This study focused on whether a brief family-based intervention for toddlers, the Family Check-Up (FCU), designed to address parent management skills and prevent early conduct problems, would have collateral effects on maternal depressive symptoms and subsequent child emotional problems. Method: Parents with toddlers were recruited from the Women, Infants, and Children Nutritional Supplement Program based on the presence of socioeconomic, family, and child risk (N= 731). Families were randomly assigned to the FCU intervention or control group with yearly assessments beginning at child age 2. Maternal depressive symptoms were measured using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale at child ages 2 and 3. Child internalizing problems were collected from primary caregivers, alternative caregivers, and teachers using the Child Behavior Checklist at ages 7.5 and 8.5. Results: Structural equation models revealed that mothers in families randomly assigned to the FCU showed improvements in depressive symptoms from child age 2 to 3, which in turn were related to lower levels of child depressed/withdrawal symptoms as reported by primary caregivers, alternative caregivers, and teacher at ages 7.5-8.5. Conclusions: Findings suggest that a brief, preventive intervention improving maternal depressive symptoms can have enduring effects on child emotional problems that are generalizable across contexts. As there is a growing emphasis for the use of evidence-based and cost-efficient interventions that can be delivered in multiple delivery settings serving low-income families and their children, clinicians and researchers welcome evidence that interventions can promote change in multiple problem areas. The FCU appears to hold such promise. Keywords: maternal depressive symptoms; child emotional problems; Family Check-Up; parenting intervention EFFECT OF MATERNAL DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS ON CHILD INTERNALIZING Public Health Significance: This study suggests that a brief, home-based, preventive intervention such as the Family Check-Up can have meaningful long-term effects on children’s emerging emotional problems. Although initially designed to improve children’s conduct problems by improving parenting practices, in the current study the Family Check-Up contributed to both improvements in maternal depressive symptoms during the toddler years and subsequent reductions in school-age emotional problems. 2 EFFECT OF MATERNAL DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS ON CHILD INTERNALIZING 1 Introduction Maternal depression is among the most robust and well-replicated risk factors for depressionspecific and more general psychopathological symptoms in offspring (Goodman et al., 2011). Maternal depression during early childhood has been linked to greater risk for concurrent (Murray & Cooper, 1997; Weinberg & Tronick, 1998) and long-term (Luoma et al., 2001) emotional problems. However, only a few studies have been carried out among school-age children and longitudinal studies spanning from early to middle childhood are even rarer (Bagner, Pettit, Lewinsohn, Seeley, & Jaccard, 2013; Luoma et al., 2001). Further research is needed to explore the association between early exposure to maternal depression and children’s long-term risk for emotional problems during the school-age period. There is an established literature on the effectiveness of parenting interventions aimed at preventing emotional and behavioral problems in early childhood (Baydar, Reid, & WebsterStratton, 2003; Olds, 2002). An example of a successful parenting intervention of this type is the Family Check-Up (FCU). The FCU is a family intervention and treatment designed to improve children’s adjustment across settings by motivating parents to address family management practices. The FCU was originally designed to address early child conduct problems, but has been shown to have positive collateral effects on inhibitory control and verbal skills (Lunkenheimer et al., 2008) and emotional problems in early childhood (Shaw, Connell, Dishion, Wilson, & Gardner, 2009). Parenting-focused interventions such as the FCU might facilitate collateral child outcomes by improving maternal well-being. Several theorists have noted how maternal depression might compromise a parent’s ability to be contingently responsive and actively engaged to their children’s socioemotional needs (Belsky, 1984). In one of the few studies to examine maternal depression as a mediator of intervention effects, Hutchings, Bywater, Williams, Lane, and Whitaker (2012) found EFFECT OF MATERNAL DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS ON CHILD INTERNALIZING 4 that improvements in maternal depressive symptoms mediated improvements in child behavior following attendance in the Incredible Years Parenting program. However, the sole reliance on maternal reports for reporting of both maternal depression and later child problem behavior may have inflated associations because of reporting bias. The current study was conducted to determine if the FCU would be directly or indirectly associated with lower levels of school-age emotional problems by improving maternal depressive symptoms in early childhood. Early childhood (ages 2 and 3) is a sensitive period of vulnerability to effects of maternal depression and a critical phase in which to examine its interplay with child emotional problems. Additionally, child’s adaptation to the demands of school represents an important area of investigation, as successful adjustment in these early school years is associated with avoidance of psychosocial problems in adulthood, such as drug and alcohol use disorders (Crum et al., 2006; Fothergill et al., 2008). We hypothesized that there would only be a modest direct effect of the intervention on school-age emotional problems, but an indirect effect on children’s school-age emotional problems for those mothers showing an improvement in depressive symptoms. To extend the methodological rigor of past research ((Barker, Copeland, Maughan, Jaffee, & Uher, 2012; Hutchings et al., 2012), the two hypotheses were tested using three informants of child behavior and two different contexts when children were in middle childhood. Methods Participants Participants included 731 mother–child dyads recruited between 2002 and 2003 from WIC programs in the areas of Pittsburgh, PA, Eugene, OR, and Charlottesville, VA (Dishion et al., 2008). Families were approached at WIC sites and invited to participate if they had a son or daughter between 2 years 0 months and 2 years 11 months of age, following a screen to ensure that they met EFFECT OF MATERNAL DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS ON CHILD INTERNALIZING 5 the study criteria by having socioeconomic, family, and/or child risk factors for future behavior problems. Two or more of the three risk factors were required for inclusion in the sample. The flow of participants through the recruitment and randomization procedures is shown in Figure 1. Retention Of the original 731 families, 659 (90%), 629 (86%), 622 (85%), 568 (78%), and 565 (77%) participated at the follow-up at ages 3, 4, 5, 7.5, and 8.5 respectively. Selective attrition analyses revealed no significant differences in attrition by project site, children’s race, ethnicity, income, gender, children’s emotional problems, or intervention status. Procedures Home observation assessment protocol. Caregivers (i.e., predominantly mothers and, if available, alternative caregivers, such as fathers or grandmothers) and children who agreed to participate in the study were scheduled for a 2.5-hour home visit. During the assessment, caregivers completed questionnaires and children engaged in a series of structured tasks with their parents or the examiner. Similar procedures were repeated at ages 3, 4, 5, 7.5, and 8.5, with modifications made to adjust for the child’s developmental status. For purposes of the current study, data from the ages 2, 3, 7.5, and 8.5 assessments were used. The Family Check-Up in the current study. The intervention model used in this study is the Family Check-Up (FCU), a brief, ecologically-based program based on motivation interviewing techniques (also see Dishion et al., 2008). The key components of the FCU that differentiate it from standard clinical care are: it (a) utilizes a health maintenance model, (b) derives much of its power from a comprehensive assessment, and (c) emphasizes motivating change. Following the initial assessment at age 2, primary caregivers and the target child were randomly assigned to the intervention condition (n = 367, 50.2%) assessments using a computer- EFFECT OF MATERNAL DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS ON CHILD INTERNALIZING 6 generated sequence. Randomization was balanced by gender to assign an equal number of boys and girls in each group. Those in the control condition received WIC services (e.g., food vouchers) but no intervention from therapists. Primary caregivers assigned to the FCU were scheduled to meet with a parent consultant for two or more sessions, depending on the family’s preference. The three meetings in which the primary caregiver and/or alternate caregiver were typically involved include an assessment meeting, an initial contact meeting, and a feedback session. Families assigned to the FCU received a $25 gift certificate for completing the feedback session. Measures Demographics questionnaire. A demographics questionnaire was administered to the mothers during the age 2, 3, 4, 5, 7.5, and 8.5 visits. For purposes of the present study, we used data on parent income, parent education, project site, and child gender collected at age 2 as covariates. Maternal depressive symptoms. The CES-D (Radloff, 1977) is a 20-item measure of depressive symptomatology that was administered at each assessment. For purposes of the current study, CES-D reports were used from the age 2 and 3 home assessments. Participants report how frequently they have experienced a list of depressive symptoms during the past week on a scale ranging from 0 (less than a day) to 3 (5–7 days). For the current sample, internal consistencies were .76 and .75 at the respective age 2 and 3 assessments. Child emotional problems at home. The CBCL is a 120 item parent questionnaire for assessing emotional and behavioral problems in 4- to 18-year-olds (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). Primary caregivers (PC) and alternative caregivers (AC) completed the CBCL at the age 7.5 and 8.5 assessments. For the purposes of the current study, the 9-item depressed/withdrawn subscale was used in the analysis to measure child emotional problems at home. The internal consistency for PC ratings was .77 and .76 at ages 7.5 and 8.5, respectively. EFFECT OF MATERNAL DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS ON CHILD INTERNALIZING 7 Child emotional problems at school. To measure teacher-reported child emotional problems in the classroom, the depressed/withdrawn factor from the Teacher Report Form (TRF; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) was used. The TRF was administered to the primary teacher of study participants at ages 7.5 and 8.5. For the purposes of the current study, a very similar 8-item depressed/withdrawn subscale utilized with parents was used in the analysis. Internal consistency for the 8-item scale was .80 and .79 at ages 7.5 and 8.5, respectively. Missing Data. Among the 731 participants included in the analysis, 17.1% had missing data on primary caregiver reports of child internalizing problems (22.9% at age 7 and 24.4% at age 8), 30.2% on alternative caregiver reports of child internalizing problems (41.8% at age 7 and 43.5% at age 8), and 38% on teacher reports of child internalizing problems (57.4% at age 7 and 48.6% at age 8). Missingness on these variables was not associated with the values of other study variables or each other, and Little’s MCAR test yielded a nonsignificant chi-square statistic (χ2(91)=97.367, ns), which suggests that these data were missing at random. Because of these high levels of missing teacher reports, either report was used as the outcome when only one age teacher report was available. A mean of the two scores was used when data were available at both time points. To remain consistent across reporters, this approach was used for primary caregiver, alternative caregiver, and teacher reports and yielded 609 (83%), 512 (70%), and 451 available cases (62%), respectively. Results Analytic strategy Structural equation modeling (SEM) was utilized using maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors (MLR) in Mplus 7.11 (Muthén & Muthén, 2013). MLR is robust to nonnormality and adjusts for missing data by estimating parameters of all available data for the estimation of a specific parameter (Muthén & Muthén, 2013). A model was first computed to EFFECT OF MATERNAL DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS ON CHILD INTERNALIZING 8 examine whether random assignment to the FCU would be associated with lower levels of child depressed/withdrawn symptoms. We included all three informants in the same model to account for the overlapping effects among reporters. Next, we explored whether random assignment to the FCU would be associated with lower levels of child depressed/withdrawn symptoms as reported by primary caregivers, alternative caregivers, and teacher at ages 7.5-8.5 through improvements in maternal depressive symptoms from child age 2 to 3. A statistical test of the significance of the indirect effect from the intervention to the change in maternal symptoms to the level of child depressed/withdrawn symptoms was examined. Standard errors for indirect effects were calculated using the delta method described by MacKinnon and colleagues (Mackinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002). Based on the project’s preventive nature, this study used an intent-to-treat design in all analyses. Thus, all participants randomly assigned to either the treatment (n = 367) or control group (n = 364), regardless of their level of participation in the intervention, were included in the analyses. Covariates used in the analysis were parent income, parent education, project site (Eugene, OR, served as the reference group), and child gender (female = 1). Descriptive Statistics Table 1 provides means, standard deviations, and inter-correlations for the study’s primary variables. Correlations between variables were largely in the expected direction. Direct effect of intervention on child emotional problems Our first goal was to test the direct effect of the FCU intervention on child depressed/withdrawn symptoms. As shown in the full model in Figure 2, intervention group status was not significantly related to primary caregiver (β = -0.02, ns), alternative caregiver (β = 0.08, ns), or teacher reports (β = 0.03, ns) of child depressed/withdrawn symptoms. EFFECT OF MATERNAL DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS ON CHILD INTERNALIZING Indirect effect of FCU on child emotional problems through improvements in maternal depressive symptoms As previously reported in Shaw et al. (2009), mothers in the intervention group reported a significantly greater decrease in depressive symptoms than control mothers (d = .18). Next, we examined whether this reduction in maternal depressive symptoms was linked to improvements in child depressed/withdrawn symptoms at ages 7.5 and 8.5. As shown in Figure 2, higher levels of maternal depressive symptoms at age 3 predicted higher levels of child depressed/withdrawn symptoms at 7.5 and 8.5, reported by primary caregivers (β= .21, p < .01). We next examined the significance of the indirect effect from intervention to changes in maternal depressive symptoms to child depressed/withdrawn symptoms. These analyses confirmed an indirect effect of the intervention on child depressed/withdrawn symptoms through improvements in maternal depressive symptoms (β= -.02, p < .05). κ2, an effect size measure for mediation models, was .058 suggesting a small effect size (Preacher & Kelley, 2011). Next, we examined the pathway from the intervention to changes in maternal depressive symptoms to alternative caregivers’ and teacher reports of child depressed/withdrawn symptoms. In both models, higher maternal depressive symptoms predicted higher levels of child depressed/withdrawn symptoms at 7.5 and 8.5, reported by alternative caregivers (β= .13, p < .01) and by teachers (β = .16, p < .01). Additionally, there was a significant indirect effect of the intervention on alternative caregiver (β= -.01, p < .05; κ2 = .01) and teacher (β= -0.01, p < .05; κ2 = .02) reports of child depressed/withdrawn symptoms via changes in maternal depressive symptoms. Discussion The present study examined whether reductions in maternal depressive symptoms serve as a mediator of intervention effects on children’s school-age emotional problems. In accord with our 9 EFFECT OF MATERNAL DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS ON CHILD INTERNALIZING 10 hypothesis, reduction in maternal depressive symptoms was a significant mediator of intervention effects on child emotional problems, reported by primary caregivers, alternative caregivers, and teachers. Although these effects were indirect, it is notable that a brief preventive intervention contributed to both improvements in maternal depressive symptoms and reductions in child emotional problems during a formative developmental period. We have now shown that improving maternal depressive symptoms during the toddler period has positive consequences not only for child’s short-term behavioral health, but also for the child’s longer-term functioning across context. These results are also consistent with prior findings linking remission of maternal depressive symptoms with reductions in children's depression, anxiety, and disruptive behavior diagnoses and symptoms (Weissman, Pilowsky, Wickramaratne, & et al., 2006). Similarly, in a review of treatment and observational studies of depressed parents, Gunlicks and Weissman (2008) found reductions in parental depression to be consistently linked to improvement in child outcomes across study types. It is noteworthy that although the FCU was originally designed to reduce children’s disruptive behavior problems, in the current study collateral benefits were found for children’s emotional problems. While there is a rather modest indirect effect, the small effect sizes are also consistent with some previous reports on collateral outcomes (e.g., Shaw et al., 2009). Despite the small effect sizes, multi-impact interventions for children with emotional problems may be especially important based on the high rate of co-occurring psychopathology among children with either conduct or emotional problems (Connell et al., 2008). In addition, the main findings could have important implications for reducing the likelihood of enduring emotional problems and cascading effects of internalizing problems into other domains of adjustment (Masten et al., 2005) Although the current results are promising, the findings must be tempered with an appreciation of study limitations. First, the study was originally designed to test the effect of the EFFECT OF MATERNAL DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS ON CHILD INTERNALIZING 11 intervention for children with conduct problems. It is unknown whether these findings will generalize to other samples of children or to children who have emotional problems without elevated conduct problems. Second, there was considerable loss of teacher report data at two of the three sites. However, an analysis of the participants with missing data on teacher ratings does not suggest selective attrition. Lastly, it is possible that genetics play a role in both improvements in maternal depressive symptoms as well as the development of child emotional problems. However, the current study involved biologically-related family members, thereby limiting understanding of the role of genetic and/or environmental underpinnings of maternal depression and child psychopathology. Alternative designs, such as adoption and children of twin studies, have the potential to disentangle environmental effects of parental depression from genetic influences. Child emotional problems are a serious public health burden. A review of the evidence-base of psychosocial treatment outcome studies for depressed youth concluded that cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is a well-established intervention approach for depressed children (David-Ferdon & Kaslow, 2008). There has also been a growing emphasis for the use of evidence-based and costefficient interventions that can be delivered in multiple delivery settings and that can promote change in multiple problem areas. The FCU appears to hold such promise and importantly in the current study, was indirectly associated with improvements in children’s long-term emotional problems for families that were not seeking treatment. 12 EFFECT OF MATERNAL DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS ON CHILD INTERNALIZING Table 1 Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations Among Variables Used in Analyses 1. Maternal Depressive Symptoms (age 2) 2. Maternal Depressive Symptoms (age 3) 3. Teacher Report of Child Depressed/Withdrawn Symptoms (age 7) 4. Teacher Report of Child Depressed/Withdrawn Symptoms (age 8) 5. PC Report of Child Depressed/Withdrawn Symptoms (age 7) 6. PC Report of Child Depressed/Withdrawn Symptoms (age 8) 7. AC Report of Child Depressed/Withdrawn Symptoms (age 7) 8. AC Report of Child Depressed/Withdrawn Symptoms (age 8) Mean SD 1. -.42** 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. .07 .19** .03 .09 .35** -- .16** .19** .23** .30** -- .17** .23** .16** .28** .63** -- .13** .14** .11 .126* .46** .40** -- .06 .14** .25** .25** .44** .47 .62** 57.95 8.13 57.30 7.71 56.98 7.82 16.75 10.66 8. -- 15.39 10.95 -- 58.87 8.13 Note. t scores are provided in presenting descriptive statistics for the CBCL externalizing, although raw scores were used for testing hypotheses in models to avoid potential age and gender corrections. PC= primary caregiver; AC= alternative caregiver. * p < .05. ** p < .01. 7. 56.17 7.07 -- 56.45 7.25 EFFECT OF MATERNAL DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS ON CHILD INTERNALIZING Figure 1. Participant Flow Chart 13 EFFECT OF MATERNAL DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS ON CHILD INTERNALIZING 14 Figure 2. Indirect effect of Family Check-Up assignment on primary caregiver, alternative caregiver, and teacher report of child internalizing behavior through improvements in maternal depressive symptoms: χ2 (5) = 11.41, p = .04; comparative fit index = .97; root mean square error of approximation =.04; standard root mean residual =.02. Covariates used in the analysis were parent income, parent education, project site (Eugene, OR, served as the reference group), and child gender (female = 1). Model estimates are standardized and provided for significant pathways only. Nonsignificant modeled pathways are illustrated by gray dotted lines. * p < .05. ** p < .01. EFFECT OF MATERNAL DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS ON CHILD INTERNALIZING 15 References Achenbach, T. M., & Rescorla, L. A. (2001). Manual for the ASEBA School-age Forms & Profiles: An Integrated System of Multi-informant Assessment: Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families/Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA). Bagner, D. M., Pettit, J. W., Lewinsohn, P. M., Seeley, J. R., & Jaccard, J. (2013). Disentangling the temporal relationship between parental depressive symptoms and early child behavior problems: A transactional framework. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 42, 78-90. Barker, E. D., Copeland, W., Maughan, B., Jaffee, S. R., & Uher, R. (2012). Relative impact of maternal depression and associated risk factors on offspring psychopathology. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 200, 124-129. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.092346 Baydar, N., Reid, M. J., & Webster-Stratton, C. (2003). The role of mental health factors and program engagement in the effectiveness of a preventive parenting program for Head Start mothers. Child Development, 74, 1433-1453. Belsky, J. (1984). The determinants of parenting: a process model. Child Development, 55, 8396. Connell, A. M., Bullock, B. M., Dishion, T. J., Shaw, D., Wilson, M., & Gardner, F. (2008). Family intervention effects on co-occurring early childhood behavioral and emotional problems: a latent transition analysis approach. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36, 1211-1225. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9244-6 Crum, R. M., Juon, H. S., Green, K. M., Robertson, J., Fothergill, K., & Ensminger, M. (2006). Educational achievement and early school behavior as predictors of alcohol-use EFFECT OF MATERNAL DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS ON CHILD INTERNALIZING 16 disorders: 35-year follow-up of the Woodlawn Study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 67, 75-85. David-Ferdon, C., & Kaslow, N. J. (2008). Evidence-Based Psychosocial Treatments for Child and Adolescent Depression. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 37(1), 62-104. doi: 10.1080/15374410701817865 Dishion, T. J., Shaw, D., Connell, A. M., Gardner, F., Weaver, C., & Wilson, M. (2008). The family check-up with high-risk indigent families: preventing problem behavior by increasing parents' positive behavior support in early childhood. Child Development, 79, 1395-1414. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01195.x Fothergill, K. E., Ensminger, M. E., Green, K. M., Crum, R. M., Robertson, J., & Juon, H. S. (2008). The impact of early school behavior and educational achievement on adult drug use disorders: a prospective study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 92, 191-199. Goodman, S. H., Rouse, M. H., Connell, A. M., Broth, M. R., Hall, C. M., & Heyward, D. (2011). Maternal depression and child psychopathology: a meta-analytic review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 14(1), 1-27. doi: 10.1007/s10567-010-0080-1 Hutchings, J., Bywater, T., Williams, M. E., Lane, E., & Whitaker, C. J. (2012). Improvements in Maternal Depression as a Mediator of Child Behaviour Change. Psychology, 3, 795. Lunkenheimer, E. S., Dishion, T. J., Shaw, D. S., Connell, A. M., Gardner, F., Wilson, M. N., & Skuban, E. M. (2008). Collateral benefits of the Family Check-Up on early childhood school readiness: indirect effects of parents' positive behavior support. Developmental Psychology, 44, 1737-1752. doi: 10.1037/a0013858 EFFECT OF MATERNAL DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS ON CHILD INTERNALIZING 17 Luoma, I., Tamminen, T., Kaukonen, P., Laippala, P., Puura, K., Salmelin, R., & Almqvist, F. (2001). Longitudinal study of maternal depressive symptoms and child well-being. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 40, 1367-1374. Mackinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., Hoffman, J. M., West, S. G., & Sheets, V. (2002). A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods, 7, 83-104. Masten, A. S., Roisman, G. I., Long, J. D., Burt, K. B., Obradović, J., Riley, J. R., . . . Tellegen, A. (2005). Developmental cascades: linking academic achievement and externalizing and internalizing symptoms over 20 years. Developmental Psychology, 41, 733. Murray, L., & Cooper, P. (1997). Effects of postnatal depression on infant development. Archives of disease in childhood, 77, 99-101. Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2013). Mplus User's Guide: Statistical Analysis with Latent Variables : User's Guide (Version 7.11): Muthén & Muthén. Olds, D. L. (2002). Prenatal and infancy home visiting by nurses: From randomized trials to community replication. Prevention Science, 3, 153-172. Preacher, K. J., & Kelley, K. (2011). Effect size measures for mediation models: quantitative strategies for communicating indirect effects. Psychological Methods, 16, 93. Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385-401. Shaw, D. S., Connell, A. M., Dishion, T. J., Wilson, M. N., & Gardner, F. (2009). Improvements in maternal depression as a mediator of intervention effects on early childhood problem behavior. Development and Psychopathology, 21, 417-439. EFFECT OF MATERNAL DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS ON CHILD INTERNALIZING 18 Weinberg, M. K., & Tronick, E. Z. (1998). The impact of maternal psychiatric illness on infant development. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 59 Suppl 2, 53-61. Weissman, M. M., Pilowsky, D. J., Wickramaratne, P. J., & et al. (2006). Remissions in maternal depression and child psychopathology: A star*d-child report. JAMA, 295(12), 1389-1398.