DRECP species account for coast horned lizard

advertisement

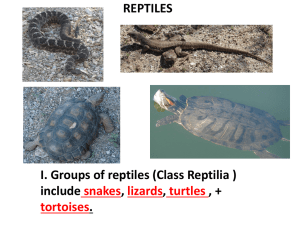

DRAFT March 2012 REPTILES Coast Horned Lizard (Phrynosoma blainvillii) Coast horned lizard (Phrynosoma blainvillii a.k.a., Phrynosoma coronatum blainvillii) Legal Status State: Species of Special Photo courtesy of Kathryn Calderala. Concern Federal: None Critical Habitat: N/A Recovery Planning: N/A Notes: State status applies to Phrynosoma blainvillii. Phrynosoma coronatum blainvillii was previously listed as a Category 2 Candidate Species in 1982 (47 FR 58454–58460) and again in 1994 (59 FR 58982–59028). Taxonomy The following discussion of coast horned lizard taxonomy is taken primarily from Klauber (1936) and Montanucci (2004). The coast horned lizard was first described as Agama coronate by De Blainville (1835) based on a specimen collected by P.E. Botta. It was soon ascribed to Phrynosoma blainvillii by John Edward Gray in 1839 (Beechey et al. 1839). However, the taxonomy of the coast horned lizard was and continues to be a subject of contention. Various papers have ascribed various forms of the coast horned lizard to other species or subspecies with revisions made in 1893 (Stejneger), 1894 (Van Denburgh), 1921 (Barbour), 1922 (Schmidt), and 1932 (Terron), among others. Linsdale (1932) recognized only one species (P. coronatum), while Reeve (1952) indicated a single species composed of five subspecies. Jennings and Hayes (1994) list two subspecies of the coast horned lizard: P. c. blainvillii and P.c. frontale. As many as six subspecies have been ascribed to the coast horned lizard (SDMNH 2011): San Diego horned lizard (P. c. blainvillii), Cape horned lizard (P. c. coronatum), California horned lizard (P. c. frontale), central peninsular horned lizard (P. c. jamesi), northern peninsular horned lizard (P. c. schmidti), and Cedros Island horned lizard (P. c. cerroense). 1 Species Accounts March 2012 DRAFT March 2012 REPTILES Coast Horned Lizard (Phrynosoma blainvillii) Prior to 1997, two of these subspecies, P. c. blainvillii and P.c. frontale, were recognized, but Brattstrom (1997) has demonstrated that the two subspecies were synonymous. More recently, Crother (2008) renamed coast horned lizard Blainville’s horned lizard (P. blainvillii). However, because the California Department of Fish and Game Special Animals List (CDFG 2011a) still retains the coast horned lizard as the common name for the special-status species, this account also refers to coast horned lizard. Information in this account would also apply to Blainville’s horned lizard because only the scientific and common names have been revised. A more recent examination of coast horned lizard taxonomy by Leaché et al. (2009), based on ecological, morphological and genetic (mtDNA nuclear DNA) characteristics, suggests “… there are three ecologically divergent and morphologically diagnosable species within the P. coronatum complex.” However, the authors go on to state that the grouping of the P. coronatum complex into three [full] species “… is not supported by all of the operational species criteria evaluated in this study …” Distribution General As the name implies, the coast horned lizard is found primarily in coastal areas of the southwestern coast of the United States and the Baja Peninsula of northwestern Mexico (Figure 1). Although little is known of the historical range of the coast horned lizard, according to Jennings (1998, cited in SAWA 2004), the species was found from the Transverse Ranges of Kern and Santa Barbara Counties, south along the coast and inland valleys to the tip of the Baja Peninsula, Mexico. It is reported to have disappeared from 35% to 45% of its historical habitat (Jennings and Hayes 1994). 2 Species Accounts March 2012 DRAFT March 2012 REPTILES Coast Horned Lizard (Phrynosoma blainvillii) Figure 1. Overall Range of Phrynosoma Coronatum (Source: Leaché et al. 2009) Within California, in addition to coastal areas generally south of San Francisco, the coast horned lizard crosses the coastal ranges into the southern areas of the Central Valley, as well as the fringing desert side of the San Gabriel, San Bernardino, San Jacinto, and the more southern Peninsular ranges (Figure SP-R3). Within the Central Valley, its range extends across the Tejon Pass/Taft area and then follows the lower foothills of the Sierra Nevada Range in a narrow band as far north as Butte County. Distribution and Occurrences within the Plan Area Historical The range of the coast horned lizard extends to the western portion of the Desert Renewable Conservation Plan (DRECP) Area. There are 15 3 Species Accounts March 2012 DRAFT March 2012 REPTILES Coast Horned Lizard (Phrynosoma blainvillii) historical (i.e., before 1990) occurrences of coast horned lizard in the Plan Area and an additional 31 occurrences that have an unknown observation date (Figure SP-R3) (CDFG 2012; Dudek 2011). These occurrences are generally along the western and southern boundaries of the Plan Area along the base of the San Gabriel and San Bernardino Mountain ranges, with one disjunct record from 1949 east of Twentynine Palms. Recent There are 39 current (i.e., since 1990) occurrences of coast horned lizard in the Plan Area (CDFG 2012; Dudek 2011). These occurrences generally overlap with the historical occurrences along the western and southern boundaries of the Plan Area along the base of the San Gabriel and San Bernardino Mountain ranges, but also include two occurrences at the base of the Tehachapi Mountains north and south of State Highway 58 (Figure SP-R3). Natural History Habitat Requirements The coast horned lizard is found in a fairly wide variety of habitats within its range (Stebbins 1985; CDFG 2000; SAWA 2004; UC Davis 2011). These habitats can include various scrublands, grasslands, coniferous and broadleaf forests, and woodlands. It can range from the coast to elevations of 6,000 feet in the Southern California mountains (CDFG 2000). It is most common in mid-elevations of the coastal mountains and valleys within open habitat that offer good opportunities for sunning. It is often associated with sandy soils in which it will bury itself; these often support ant colonies (Behler and King 1979). The coast horned lizard needs loose, fine soils with open areas for basking and shrubs for refugia (Jennings and Hayes 1994, cited in UC Davis 2011). Fischer et al. (2002) report the primary determinants of coast horned lizard presence and abundance in coastal mountain areas are 1) a lack of Argentine ants (Linepithema humile) (and the presence of native ant species), 2) the presence of chaparral plants, and 3) the presence of sandy soils. 4 Species Accounts March 2012 DRAFT March 2012 REPTILES Coast Horned Lizard (Phrynosoma blainvillii) In the Plan Area, it appears that the desert fringing areas that support the coast horned lizard are generally the shrubby areas at the desert base or mid-elevations of the San Gabriel and San Bernardino mountains, and some areas around Yucca and Morongo valleys. Foraging Requirements The coast horned lizard is considered to be myrmecophagous, or an ant-eating specialist, although it is reported that they will take other small insect prey, including beetles, wasps, grasshoppers, and caterpillars (CDFG 2000). Ants have been estimated as comprising more than 90% of the diet for some local populations (Pianka and Parker 1975 and Suarez et al. 2000, cited in UC Davis 2011). They almost exclusively favor native harvester ants (Pogonomyrmex desertorum, P. rugosus, P. californicus, and Crematogaster californica) (Suarez and Case 2002; Zipcodezoo 2011). Coast horned lizards that are forced to eat the introduced Argentine ant experience reduced fitness (Suarez and Case 2002). Reproduction Coast horned lizards mate and reproduce in spring and early summer, and depending upon local conditions and climate, they are generally active through the summer and into the early fall months. In some areas, they may aestivate during especially hot summer months. During the colder winter months, they hibernate. In Southern California, the male coast horned lizard reproductive cycle begins during mid- to late March and ends in June (Goldberg 1983). Usually a clutch of 6 to 17 eggs is laid (Hollingsworth and Beaman 2001), with a mean clutch size of 13 (CDFG 2000). Eggs hatch in about 2 months (Hollingsworth and Beaman 2001) in the summer and early fall. These hatchlings will reach sexual maturity in 2 to 3 years (Zipcodezoo 2011). 5 Species Accounts March 2012 DRAFT March 2012 REPTILES Coast Horned Lizard (Phrynosoma blainvillii) Dec Nov Oct Sep Aug July June May April March Feb Jan Table 1. Key Seasonal Periods for the Coast Horned Lizard Breeding X X X X General Activity X X X X X X Hibernation X X X X X X X ________________ Notes: Activity can vary with location and yearly differences in temperature. Sources: Hollingsworth and Beaman 2001; Zipcodezoo 2011. Movement The coast horned lizard exhibits extremely high site fidelity (Zipcodezoo 2011), and pronounced seasonal movement or migration has not been reported (CDFG 2000). They apparently lack territorial behavior, although it has been reported that males will joust for mating purposes (CDFG 2000). Daily movement distances average 154 feet per day (Whitford and Bryant 1979, cited in Zipcodezoo 2011). There are no movement and dispersal data specifically for the coast horned lizard, but horned lizards as a group show limited home ranges, usually less than 5 acres (Munger 1984). However, daily foraging distances and home range size appear to vary inversely with lower plant diversity and higher disturbance (Grant and Alberts 2005). Ecological Relationships Coast horned lizards are ant specialists. It is reported that more than 90% of their diet can consist of ants. As ant specialists, the presence of native ants in their habitat is essential (Suarez and Case 2002, Suarez et al. 2000, and Pianka and Parker 1975, as cited in UC Davis 2011). The coast horned lizard serves as prey to a wide variety of predators, including snakes, loggerhead shrike (Lanius ludovicianus), burrowing owl (Athene cunicularia), greater roadrunner (Geococcyx californianus), hawks, and domestic cats and dogs (CDFG 2000; Jennings and Hayes 1994; Shiozuki 2006). 6 Species Accounts March 2012 DRAFT March 2012 REPTILES Coast Horned Lizard (Phrynosoma blainvillii) The coast horned lizard abuts the range of the desert horned lizard (P. platyrhinos) in these areas, but apparently there is little overlap in their use of the available habitats, the coast horned lizard being found only in juniper-desert chaparral habitat, while the desert horned lizard is found in creosote bush scrub (Brattstrom 1997). Population Status and Trends Global: G3G4 (NatureServe 2011) State: Same as above Within Plan Area: Same as above The coast horned lizard has a fairly limited distribution within the Plan Area, but is widespread further toward the coast. Due to their limited range and habitats within the Plan Area, populations there are probably stable to slightly imperiled assuming that development of the lower elevations of the San Gabriel and San Bernardino Mountains remains light. Traditionally, development has been relatively light in these areas. However, should increased development pressure occur in these areas, the persistence of the coast horned lizard within the Plan Area may become more tenuous. Threats and Environmental Stressors Several threats and stressors affect the coast horned lizard, although few are extensively documented. It is reported to have disappeared from 35% to 45% of its historical habitat in California (Jennings and Hayes 1994). Figure 2 presents a simple conceptual model of threats and stressors for the coast horned lizard. 7 Species Accounts March 2012 DRAFT March 2012 REPTILES Coast Horned Lizard (Phrynosoma blainvillii) Figure 2. Simple Conceptual Model of Threats and Stressors for the Coast Horned Lizard. Chief among these is the loss of habitat by urbanization in the coastal areas of Southern California (SDNHM 2011). Accompanying this loss of habitat, areas adjacent to development are generally subject to higher disturbance and a decrease in vegetative density. As a result, horned lizards adapt by increasing their home ranges to ensure enough resources are available to them (Grant and Alberts 2005). This necessary increase in home range in disturbed areas, especially those adjacent to development, increases the probability of horned lizard mortality as they are forced to range into areas where vehicles and pets are found. A recent and highly significant threat to the coast horned lizard is the expansion of the Argentine ant (Jennings and Hayes 1994; Hollingsworth and Beaman 2001; Suarez and Case 2002; Yolo Natural Heritage Program 2009; SDNHM 2011). Argentine ants are typically associated with areas of disturbance, principally around urban development, and they displace native harvester ants, the main food of the coast horned lizard. Hatchling horned lizards fed on Argentine ants showed decreased or no growth, compared to those fed native 8 Species Accounts March 2012 DRAFT March 2012 REPTILES Coast Horned Lizard (Phrynosoma blainvillii) ant species (Suarez and Case 2002). Thus, as native ants are displaced by this biological invasion, horned lizards may be significantly affected, and may be eliminated in areas where complete dominance by Argentine ants has occurred. In conjunction with the direct habitat loss by development, an increase in wildland fires associated with adjacent highways and other activities (e.g., off-road vehicles) can impact horned lizard populations. Domestic pets, especially domestic cats, have increased predation pressure (Jennings and Hayes 1994). In the past, collecting for the curio trade and later by biological supply houses has significantly impacted the species (Jennings 1987; SDNHM 2011). However, since 1981, commercial collecting of the horned lizard has been banned (SDNHM 2011). Conservation and Management Activities Because the coast horned lizard is not listed as threatened or endangered, specific recovery plans or other management efforts for this species are lacking. However, the coast horned lizard is often included as a covered species in habitat conservation plans (HCPs). The following is a list of HCPs that include the coast horned lizard as a covered species (USFWS 2011): California Department of Corrections Statewide Electrified Fence Project; El Sobrante Landfill HCP; Fieldstone/La Costa and City of Carlsbad; Lake Mathews Multiple Species Habitat Conservation Plan (MSHCP); City of Carlsbad Habitat Management Plan; and Western Riverside County MSHCP. Data Characterization Although taxonomic and habitat relations of the coast horned lizard are well represented in the scientific literature, it appears that little is known about the distribution of the coast horned lizard within the confines of the Plan Area (i.e., desert slopes of the San Gabriel and San 9 Species Accounts March 2012 DRAFT March 2012 REPTILES Coast Horned Lizard (Phrynosoma blainvillii) Bernardino mountains). As this species is primarily coastal in nature, there are significant data gaps in its specific range (especially along the Mojave River), habitat characteristics, and abundance within these areas. Additionally, the nature and extent of Argentine ants within these areas is poorly understood, and should be assessed. Jennings and Hayes (1994) indicate that data are needed on how domestic cats, grazing, prescribed fire, and off-road vehicles impact the coast horned lizard. Fisher et al. (2002) caution against using remote sensing for determination of abundance based on perceived habitat, since data on the single most important variable for determining presence, native ants, is not obtainable by this method. Management and Monitoring Considerations Effective management for the coast horned lizard in the Plan Area could include the following: Attempt to control (or eliminate) Argentine ants in project areas; care must be taken to not affect native ants if using pesticides; Ensure a mixture of shrub and open areas in the habitat to allow efficient thermoregulation by the coast horned lizard; Investigate re-introduction of native ants into project areas; Ensure sandy substrates; Maximize isolation by limiting public access to areas of known coast horned lizard populations to help prevent vehicle accidents and collecting; Prevent wildland fires and other disturbances that could foster the colonization of the area by Argentine ants; Close redundant or unnecessary roads to curtail vehicle travel in areas known to support the coast horned lizard For residential developments within or adjacent to occupied habitat, develop an information program (e.g., informative pamphlet) about the significance of collecting, off-road driving, and uncontrolled pets to the horned lizard; and Develop a set of best management practices and construction education programs for developments within areas likely to support the coast horned lizard. 10 Species Accounts March 2012 DRAFT March 2012 REPTILES Coast Horned Lizard (Phrynosoma blainvillii) Predicted Species Distribution in Plan Area There are 1,931,508 acres of modeled suitable habitat for coast horned lizard. Modeled suitable habitat occurs in the western portion of the Plan Area from Joshua Tree National Park north to the northern end of the High Desert Plains and Hills below 6,000 feet in elevation. Modeled suitable habitat includes grassland, forest, woodland, scrub, and chaparral communities, as well as rural areas. Modeled suitable habitat is also restricted to sandy soils (Figure SPR3). Appendix C includes specific model parameters and a figure showing the modeled suitable habitat in the Plan Area. Appendix C provides a summary of the methodology used to model DRECP Covered Species with Maxent. For the coast horned lizard, 64 occurrence points were used to train the Maxent model and 11 occurrence points were used to test the model’s performance. Overall, the Maxent model has excellent statistical support. The occurrence points occur in a limited geographical area relative to the Plan Area, increasing the predictive power of the model. Based on a natural break in the distribution of the probability of occurrence that Maxent estimates, all 100-meter grid cells with greater than 0.222 probability of occurrence were defined as coast horned lizard habitat. The Maxent model predicts 1,307,471 acres of coast horned lizard habitat, compared with 1,931,508 acres predicted by the expert model. The Maxent model predicts coast horned lizard habitat along the southwest border of the Plan Area from Bakersfield to Twentynine Palms, with the majority around known occurrences, except the northern and southern tips of the model’s prediction where occurrences are rare. The expert model predicts habitat similar to the Maxent model around occurrence samples, but also in the West Mojave where occurrence data are very scarce. Literature Cited 47 FR 58454–58460. Notice of Review: “Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Review of Vertebrate Wildlife for Listing as Endangered or Threatened Species.” December 30, 1982. 11 Species Accounts March 2012 DRAFT March 2012 REPTILES Coast Horned Lizard (Phrynosoma blainvillii) 59 FR 58982–59028. Notice of Review: “Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Animal Candidate Review for Listing as Endangered or Threatened Species.” November 15, 1994. Beechey, F., J. Richardson, N. Vigors, G. Lay, E. Bennett, R. Owen, J. Gray, W. Buckland, E. Belcher, and A. Collie. 1839. The Zoology of Captain Beechey’s Voyage. London, United Kingdom: Edward Bohn. Behler, J., and F.W. King. 1979. The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians. New York, New York: A.A. Knopf Press. Brattstrom, B. 1997. “Status of the Subspecies of the Coast Horned Lizard, Phyrnosoma coronatum.” Journal of Herpetology 31(3):434–436. CDFG (California Department of Fish and Game). 2000. Coast Horned Lizard: California Wildlife Habitat Relationships System. Sacramento, California: CDFG. CDFG. 2008. “Range Map for the Coast Horned Lizard” [Map]. Accessed November 15, 2011. http://nrm.dfg.ca.gov/ documents/ContextDocs.aspx?cat=CWHR. CDFG. 2011a. Special Animals (898 Taxa). Department of Fish and Game, Biogeographic Data Branch, California Natural Diversity Database. January 2011. Accessed December 16, 2011. http://www.dfg.ca.gov/biogeodata/cnddb/pdfs/SPAnimals.pdf. CDFG. 2011b. “Phrynosoma blainvillii.” Element Occurrence Query. California Natural Diversity Database (CNDDB). RareFind, Version 4.0 (Commercial Subscription). Sacramento, California: CDFG, Biogeographic Data Branch. Accessed December 2011. http://www.dfg.ca.gov/biogeodata/cnddb/mapsanddata.asp. Crother, B.I. 2008. Scientific and Standard English Names of Amphibians and Reptiles of North America North of Mexico, with Comments Regarding Confidence in our Understanding. 6th ed. Herpetological Circular No. 37. Ed. J.J. Moriarty. Shoreview, Minnesota: Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. 12 Species Accounts March 2012 DRAFT March 2012 REPTILES Coast Horned Lizard (Phrynosoma blainvillii) Dudek. 2011. “Species Occurrences–Phrynosoma blainvillii.” DRECP Species Occurrence Database. Updated November 2011. Fisher, R., A. Suarez, and T. Case. 2002. “Spatial Patterns in the Abundance of the Coastal Horned Lizard.” Conservation Biology 16(1): 205–215. Goldberg, S.R. 1983. “Reproduction of the Coast Horned Lizard, Phrynosoma coronatum, in Southern California.” Southwestern Naturalist 28:478–479. Grant, T., and A. Alberts. 2005. Monitoring the Effects of Natural and Anthropogenic Habitat Disturbance on the Ecology and Behavior of the San Diego Coast Horned Lizard (Phrynosoma coronatum blainvillii). USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech. Rep. PSW-GTR-195. 2005. Hollingsworth, B., and K. Beaman. 2001. Species Account for the San Diego Horned Lizard. Prepared as part of the West Mojave Habitat Conservation Plan, Bureau of Land Management, Moreno Valley, California. Jennings, M. 1987. “Impact of the Curio Trade for San Diego Horned Lizards (Phrynosoma coronatum blainvillii) in the Los Angeles Basin, California: 1885–1930.” Journal of Herpetology 21(4): 356–358. Jennings, M., and M. Hayes. 1994. Amphibian and Reptile Species of Special Concern in California, Final Report. Contract No. 8023. Sacramento, California: California Department of Fish and Game. Klauber, L. 1936. “The Horned Toads of the Coronatum Group.” Copeia 2:103–110. Leaché A., M. Kooa, C. Spencera, T. Papenfussa, R. Fisherb, and J. McGuirea. 2009. “Quantifying Ecological, Morphological, and Genetic Variation to Delimit Species in the Coast Horned Lizard Species Complex (Phrynosoma).” Proceedings of the National. Academy of Sciences 106(30):12418–12423. 13 Species Accounts March 2012 DRAFT March 2012 REPTILES Coast Horned Lizard (Phrynosoma blainvillii) NatureServe. 2011. “Phrynosoma blainvillii.” NatureServe Explorer: An Online Encyclopedia of Life. Version 7.1. Arlington, Virginia: NatureServe. Last updated July 2011. Accessed December 2011. http://www.natureserve.org/explorer. Montanucci, R. 2004. “Geographic Variation in Phyrnosoma coronatum (Lacertilia, Phrynosomatidae): Further Evidence for a Peninsular Archipelago.” Herptologica 60(1):117–139. Munger, J.C. 1984. “Home Ranges of Horned Lizards (Phrynosoma): Circumscribed or Exclusive?” Oecologica 62:351–360. Reeve, W. 1952. “Taxonomy and Distribution of the Horned Lizard Genus Phrynosoma.” The University of Kansas Science Bulletin 34(2):817–960. SDNHM (San Diego Natural History Museum). 2011. “Field Guide: Phyrnosoma Coronatum, Coast Horned Lizard.” SAWA (Santa Ana Watershed Association). 2004. “Sensitive Species of the Santa Ana Watershed: San Diego Horned Lizard (Phyrnosoma Coronatum Blainvillii).” Accessed November 23, 2011. http://www.ocwd.com/fv-427.aspx. Shiozuki, R. 2006. “Phrynosoma Coronatum, Coast Horned Lizard.” Accessed November 28, 2011. http://www.usfca.edu/ fac_staff/dever/horned%20lizard.pdf. Stebbins, R. 1985. Western Reptiles and Amphibians. Peterson Field Guides #16. Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin Company. Suarez, A., and T. Case. 2002. “Bottom-Up Effects on Persistence of a Specialist Predator: Ant Invasions and Horned Lizards.” Ecological Applications 12(1):291–298. UC Davis (University of California, Davis). 2011. “Taxon: Phrynosoma Blainvillii, Coast Horned Lizard.” Status summary: oneparagraph summary of status, including SSC priority. Accessed November 23, 2011. http://arssc.ucdavis.edu/reports/ Phrynosoma_blainvillii.html. 14 Species Accounts March 2012 DRAFT March 2012 REPTILES Coast Horned Lizard (Phrynosoma blainvillii) USFWS (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service). 2011. “San Diego Horned Lizard: Phrynosoma Coronatum Blainvillii.” Accessed November 29, 2011. http://ecos.fws.gov/speciesProfile/ profile/speciesProfile.action?spcode=C05W. Van Denburgh, J. 1922. “The Reptiles of Western North America.” Occasional Papers of the California Academy of Sciences (X). San Francisco, California: California Academy of Sciences. Yolo Natural Heritage Program. 2009. “Coast Horned Lizard (Phrynosoma Coronatum Frontale).” Draft species account. Carlsbad, California: Technology Associates. Zipcodezoo. 2009. “Phrynosoma Coronatum Blainvillii (Coast Horned Lizard).” Accessed November 23, 2011. http://zipcodezoo.com/ animals/p/phrynosoma_coronatum_blainvilli. 15 Species Accounts March 2012