action research - final project report

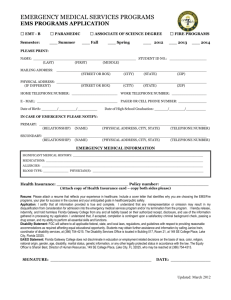

advertisement