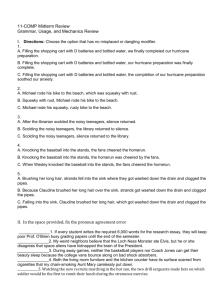

File

advertisement

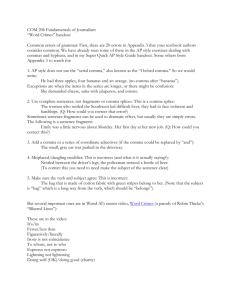

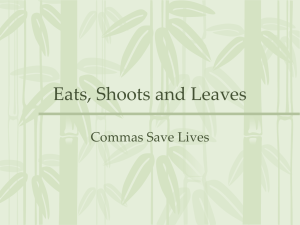

Always, Always, Always Bill Rohde The essay that follows was written for a class required for students who intended to teach English. Focusing on both writing and the teaching of writing, the course asked students to analyze their own writing habits, including elements in the writing process that gave them problems. No matter what their stage of experience, most writers hit at least one question that sends them to the nearest handbook. The assignment here asked the class to choose one matter of grammar or usage that sent them in search of answers, then to research what the handbooks had to say, and to write an essay explaining both the question and the answers. Since the students were prospective English teachers, they were to use the Modern Language Association’s (more familiarly known as MLA) system of documentation and their audience was the class itself. Bill Rohde questioned the necessity of using a comma before the last item in a series. What to Look For: Bill Rohde takes an inherently dry subject—the serial comma—and uses it to satirize composition teachers and classify students. As you read the essay, try to imagine the person behind the prose. Also keep in mind that Rohde creates a distinct personality for the narrator of the essay without ever using the first-person I. A student inquiring about the “correctness” of the serial comma finds conflicting advice in her Harbrace, her teacher’s MLA Style Manual, and the library’s Washington Post Deskbook on Style. Harbrace tells her she may write either The air was raw, dank, and gray. or The air was raw, dank and gray. Ever accommodating, the tiny, red handbook considers the comma before the conjunction “optional” unless there is “danger of misreading” (132). The MLA Style Manual, with its Bible-black cover, neither acknowledges ambivalence nor allows for options. “Commas are required between items in a series,” it clearly states in Section 2.2.4., after which it provides a typically lighthearted sample sentence: The experience demanded blood, sweat, and tears. (46) The paperback Post Deskbook, so user-friendly it suggests right in the title the handiest place to keep it, advises the student to “omit commas where possible,” as before the conjunction in a series (126-27). Apparently written on deadline, the book offers sample sentence fragments: red, white, green and blue; 1, 2 or 3(127) What should you, the composition teacher, tell this puzzled student when she approaches with her problem? Tell her she must always use the serial comma—no ifs, ands, or buts about it. Regardless of whether you believe this to be true, you must sound convincing. If the student appears satisfied with your response and thanks you, you may go back to grading papers. If, however, she wrinkles her nose or bites her lip in a display of doubt, then you may safely label her a problem student and select one of the following tailor-made responses. The struggling student appreciates any burden a teacher can remove. You should explain to her that out of sympathy for her plight—so much to keep track of when writing—you have just given her one of the Rohde / Always, Always, Always Page 1 few hard-and-fast rules in existence. Tell her to concern herself with apostrophes or sentence fragments, and not with whether the absence of a serial comma might lead to a misreading. The easily intimidated student (often ESL) should have accepted your unequivocal answer, but perhaps you do not (yet) strike her as an authority figure. Go for the throat. Say, “Obey the MLA. It is the Bible (or Koran or Bhagavad-Gita) of the discourse community to which you seek entry. Expect blood, sweat, and tears if you do not use the serial comma.” The skeptic needs an overpowering, multifarious theory to be convinced, so pull out Jane Walpole’s A Writer’s Guide and read the following: [A]ll commas indicate an up-pause in the voice contour, and this up-pause occurs after each series item up to the final one. Listen to your voice as you read this sentence: Medical science has overcome tuberculosis, typhoid, small pox, and polio in the last hundred years. Only polio, the final series item, lacks an up-pause; and where there is an up-pause, there should be a comma. The “comma and” combination before the final item also tells your readers that the series is about to close, thus reducing any chance of their misreading your sentence. (95) While that’s still soaking in, drop the names of linguists who have stated that writing is silent speech and reading is listening. Then tell her that omitting the serial comma represents an arrogant, foolish, and futile attempt to sever the natural link between speech and text. Show the visually oriented student, possibly an artist, how Chagall, Picasso, and Dali are nicely balanced, but Chagall, Picasso and Dali are not. Tell the metaphor-happy student that commas are like dividers between ketchup, mustard, and mayonnaise; fences between dogs, cats, and chickens; or borders between Israel, Syria, and Lebannon. Without them, messes result. (Dodge the fact that messes may result even if they are present.) If the student is a journalism major who cites the Deskbook as proof of the serial comma’s obsolescence, point out that her entire profession is rapidly approaching obsolescence. Add that editors who attempt to speed up reading by eliminating commas in fact slow down comprehension by removing helpful visual cues. One hopes that reading, seeing, and hearing so many strong arguments in favor of the serial comma has so utterly convinced you of its usefulness that every student from here on in will accept your rock-solid, airtight edict without question. Works Cited Achtert, Walter S., and Joseph Gibaldi. The MLA Style Manual. New York: MLA, 1985. Hodges, John C., et all. Harbrace College Handbook. New York: Harcourt, 1990. Walpole, Jane. A Writer’s Guide. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice, 1980. Webb, Robert A. The Washington Post Deskbook on Style. New York: McGraw, 1978. Rohde / Always, Always, Always Page 2