September 2013 – January 2014

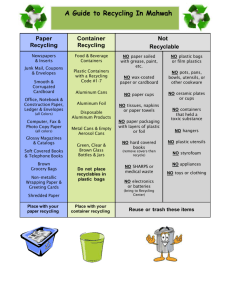

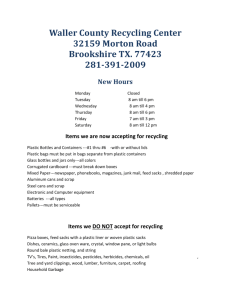

advertisement