Running head: LITERACY IN THE ENGLISH DISCIPLINE

advertisement

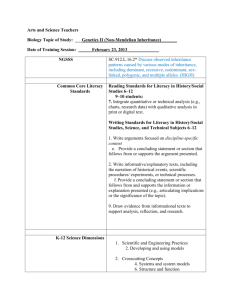

Running head: LITERACY IN THE ENGLISH DISCIPLINE Literacy as a Multidimensional Construct in the English Discipline Eric Rackley Brigham Young University-Hawaii Taylor Moyes Brigham Young University-Hawaii LITERACY IN THE ENGLISH DISCIPLINE 2 Literacy as a Multidimensional Construct in the English Discipline The differences among disciplines contribute to their unique “conceptual contexts,” which create disciplinary subcultures that have their own discourse patterns, norms of behavior and interaction, as well as expectations for producing, acquiring, and using knowledge (Grossman and Stodolsky, 1995). These disciplinary subcultures create disciplinary contexts that frame the work and conceptions of disciplinary experts and influence what counts as literacy (Shanahan and Shanahan, 2012). As the field attempts to develop a clearer understanding of literacy from various disciplinary perspectives, we aim to contribute to this knowledge base with insights into the nature of literacy from an English disciplinary perspective. The purpose of this paper is to articulate English experts’ views of literacy and how these views get operationalized in their instructional practice. This work can provide a clearer understanding about the way English experts think about literacy and the role literacy plays in their disciplinary teaching and students’ disciplinary learning. As such, this work may inform the preparation and development of secondary teachers and potentially improve secondary students’ literacy learning. Theoretical Framework and Relevant Literature McKenna and Robinson (1990) defined content area literacy as “the ability to use reading and writing for the acquisition of new content in a given discipline” (p.184). Disciplinary literacy pushes this, emphasizing the development and use of strategic disciplinary approaches to do the work of experts in the field to gain disciplinary knowledge (Moje, 2007; McConachie, Hall, Resnick, Ravi, Bill, Bintz, and Taylor, 2006; Shanahan, Shanahan, and Misischia, 2011). Disciplinary literacy is not only about learning disciplinary content, it is also about learning the ways in which knowledge of the disciplines is produced through the use of disciplinary specific habits, practices, processes, and ways of thinking and working. This body of research focuses on LITERACY IN THE ENGLISH DISCIPLINE 3 the importance of disciplinary literate practices with which, for example, mathematicians (Bass, 2006; Moses and Cobb, 2003), historians (Bain, 2005, 2006; Wineburg, 1991, 1998), scientists (Hand, Wallace, and Yang, 2004; Shanahan et al., 2011), and literary scholars (Lee, 2001; Lee and Spratley, 2010), approach the work of their disciplines. Lee (2004) argues that disciplinary literacy “is the primary conduit through which learning in the academic disciplines takes place” (p.14). To engage in meaning making in the English discipline, learners must develop critical prior knowledge and a repertoire of disciplinary literacy skills. These include knowing how literary texts are structured, typical human motivations and practices, and the use of literary devices such as symbolism, metaphor, simile, allusions, and satire. Moreover, learners in the English discipline must be able to detect and interpret literary devices, understand what counts as justifiable evidence and be able to use it to support their arguments, and be able to suspend their disbelief and enter the imaginary worlds of fictional people and places (Lee & Sprately, 2010). These examples demonstrate some of the disciplinary literacy knowledges and skills necessary for learners to construct meaning in the English discipline; yet, we know much less empirically about how English disciplinary experts actually view literacy in their field. What, for example, do they believe counts as the production of knowledge? Given the critical nature of reading, writing, and the construction of knowledge in English and other disciplines (Bain, 2005, 2006; Bass, 2006; Hand, Wallace, and Yang, 2004; Lee, 2001; Lee and Spratley, 2010; Moses and Cobb, 2003; Shanahan et al., 2011; Wineburg, 1991, 1998) and the importance of teaching students to understand, use, and when appropriate, critique, these disciplinary specific practices and processes (Moje, 2007; McConachie et al., 2006) it behooves literacy educators to have a clearer, empirical understanding of what counts as literacy from an English expert’s perspective. LITERACY IN THE ENGLISH DISCIPLINE 4 Methods This paper is part of a larger, four-stage disciplinary literacy initiative that seeks to (a) identify disciplinary experts’ conceptions of literacy, (b) identify experts’ disciplinary literacy practices, (c) develop literacy materials and tools for teaching secondary teacher candidates enrolled in a disciplinary literacy course, and (d) continue to refine these materials and tools for instructional use over time. We are in the first wave of the first stage of the initiative, focusing on English experts’ views of literacy. Site and Participants We selected participants based on their disciplinary affiliation and level of expertise. All of the participants are university English professors. They all teach at the same university and all have doctoral degrees in the field of English. They have been teaching English between three and 40 years. Their specializations vary: American Literature, British Literature, Creative Writing, and Critical Theory. They also teach a variety of university courses, including GE composition, Pacific Literature, Shakespeare, Romantic Literature, and Victorian Literature. Data Sources and Analytic Procedures Current data consist of audio recorded interviews from seven English experts. Each expert completed a 45-minute interview designed to explore his/her views of literacy, texts, motivation for literacy, and literacy teaching and learning in the English discipline. This semistructured interview consisted of 22 questions with a number of follow-up questions as appropriate. After the interviews were transcribed, we began analyzing the data. Our analytic focus was to identify the nature of English disciplinary experts’ views of literacy. Informed by methods of constant comparative analysis (Corbin and Strauss, 2008; Strauss and Corbin, 1998), we read and reread the interviews, engaging in extended micro- LITERACY IN THE ENGLISH DISCIPLINE 5 analyses individually and as a research team. We also made theoretical comparisons and wrote numerous relational statements to explore how the data fit together. Over time, through the process of open, axial, and selective coding we identified larger themes within and across the data that helped explain how English experts viewed literacy in their discipline. In practice, this process was much more iterative than captured here. We settled disagreements through discussion and continual analysis of the data, which served to refine the developing themes. Results The data suggest that to engage in meaning making in ways privileged by experts in the English discipline readers had to develop a multidimensional relationship with disciplinary texts. Moreover, English disciplinary experts conceptualized developing this reader-text relationship in their students through a multidimensional approach to disciplinary literacy instruction. A Multidimensional Reader-Text Relationship The following three dimensions helped to explain the English experts’ understanding of the disciplinary relationship with texts: heritage, cognitive, and edifying. We discuss each of these dimensions separately to describe and clarify their characteristics, but we believe that they are much more interconnected in the experts’ views and as manifest in practice. We, therefore, conceptualize them as three interlocking spheres set within a larger sphere representing the English discipline (Figure 1). This conception of literacy as a multidimensional reader-text relationship was positioned by the experts as allowing readers to go beyond the much maligned “shallow,” “surface” engagement with texts. The heritage dimension focused on understanding of texts’ historical roots and the ability to enter the larger disciplinary conversations about the text. Specifically, this means that reader must be familiar with the contexts in which literary texts are written and understood, have an LITERACY IN THE ENGLISH DISCIPLINE 6 understanding of the cultural and historical influences upon the literary texts, and know and attend to the legacy of the criticism surrounding the texts. Experts represented the heritage dimension when they talked about readers needing to “understand the social and political condition in which the text was created,” know the “background information of the text” and be able to “look at the historical period out of which a text is born or created or written.” One expert explained the heritage dimension of the reader-text relationship as knowing “the literary fathers of the texts” one reads and then being able to use that knowledge to “see how that feeds some of [the text’s] submerged material.” Knowing the historical legacy of literary texts, English experts argued, allowed readers to make sense of important disciplinary texts. Without this knowledge and the accompanying skills associated with the heritage dimension, readers of English texts would read disciplinary texts in a literary and cultural vacuum, which could not only limit their relationship with these texts, but by extension their ability to construct disciplinary appropriate meaning from these texts. In short, failure to attend to the heritage dimension would mean that readers were not engaging in a critical aspect of English disciplinary literacy. Figure 1 English Disciplinary Literacy as a Multidimensional Relationship with Texts Heritage Dimension Edifying Dimension Cognitive Dimension English Discipline LITERACY IN THE ENGLISH DISCIPLINE 7 Reading to construct disciplinary meaning, from an English expert perspective, was not simply about understanding plot. Experts claimed that to construct knowledge, readers needed “to process, think, and have a critical response to the text.” This meant, to borrow their language, interpreting, analyzing, critiquing, and “going beyond the literal meaning” of a text. These elements of the cognitive dimension focused on the mental aspects of the reader-text relationship, or the mental work that it took to make sense of English disciplinary texts. As one expert stated, constructing meaning meant that a reader needed to “engage in the contextual meaning that is afforded by in-depth analysis and critical thinking.” Another argued that reading in English demanded “a sharpened critical ability to read analytically, and to read thoughtfully, and to be able to engage actively.” Active engagement included being able to “understand the implications of what you read and then effectively analyze and respond to [and] make a judgment or statement about what you read and then participate in the conversation about it.” The cognitive dimension involved much of the intellectual work required to construct meaning of English disciplinary texts. When students could do this well, one expert suggested that it could create “better thinkers,” or perhaps, as we would argue, better disciplinary thinkers. The third dimension of the reader-text relationship view of literacy attended to the improvements that engaging with literary texts could make in a reader’s life. Therefore, we call this the edifying dimension. Developing a strong, disciplinary relationship with these texts could literally “create better humans,” and “give you a reason to live.” This relationship could also make people “rethinking the way they live their lives,” help “you make decisions to live better,” and help them “think about how they live their lives in ways that are going to make them happier and to be able to serve others better, [and] to have their relationships go better.” One expert claimed that literacy in English “is a highly spiritual pursuit.” Another stated that when LITERACY IN THE ENGLISH DISCIPLINE 8 approached in disciplinary ways, English texts could actually “make your life better and make you make better decisions to live better.” The emphasis on the verb “make” suggests the power this English expert believed appropriately negotiated texts could have over a reader to “ideally . . . change their lives.” One English experts believed so much in the edifying quality of the texts in her discipline, that she stated that even if a reader read disciplinary texts at a surface level he “would still be better off” than if he never read them. Taken together, the heritage, cognitive, and edifying dimensions of the reader-text relationship suggest that the construction of meaning in the English discipline, from an English experts’ perspective, is a multidimensional process that draws upon various elements valued in the discipline. Having addressed these briefly, the next section explores how English experts go about developing this multidimensional reader-text relationship in their students. Developing the Reader-Text Relationship In addition to identifying heritage, cognitive and edifying dimensions as part of the reader-text relationship, experts also identified a multidimensional approach for developing disciplinary readers’ relationships with texts by focusing on reading, writing, and talking about the texts. As one expert stated, “I make them read. I make them write. I make them talk.” As with the three dimensions of the reader-text relationship, reading, writing, and talking should not be viewed as isolated practices used in service of developing students’ English disciplinary literacy. The experts understood them as overlapping and dynamic ways to develop students’ literacy skills and practices. First, reading consisted of careful analysis and interpretation; exploring, for example, how the historical context in which a “text is born.” Experts stated that they taught their students “what is literally happening in a text” and then taught “them the implications of what they read” LITERACY IN THE ENGLISH DISCIPLINE 9 in order to “understand the meaning” of the text. Experts felt that they had an obligation to “encourage and challenge readers to encounter texts they wouldn’t normally seek out on their own.” Moreover, English experts suggested that when reading texts within the English discipline, readers must read “analytically” and “thoughtfully” as it is an essential step in developing this reader-text relationship and then “put it in practice by writing to use those disciplinary skills as well.” Although limited in this round of data, experts viewed writing as a knowledge-production tool that helped students develop a stronger relationship with disciplinary texts and deepen their understanding of the texts. Referring to writing as a meaning making practice, one expert said that readers understood disciplinary texts simply “through practicing [writing].” Writing was a potentially powerful way to develop this reader-text relationship and gave the reader the opportunity to construct disciplinary knowledge of literary texts. We anticipate writing playing a more prominent role as a way to develop disciplinary literacy in English as we continue to collect and analyze data. Experts also claimed that they talked to their student about texts, taught them how to talk to each other about texts, and taught them how to “ask the right questions” about texts. By talking about the texts, experts claim the reader is able to “join a literacy community” and “contribute to the larger disciplinary conversation about the text under investigation.” Literacy in the English discipline is not just about reading the words, but about “conversing about ideas.” Experts stated that disciplinary knowledge not only comes from the disciplinary text itself, but also the readers’ own interpretations and readings of the text and the conversations they have to construct meaning. LITERACY IN THE ENGLISH DISCIPLINE 10 Although separate practices, reading, writing, and talking were often discussed in combination with one another because the experts viewed them as iterative processes in the development of the reader-text relationship. Explaining how he helped his students engage with texts, one expert said, “You have to process [the text] and communicate effectively. You have to read and understand the implications of what you read and then effectively analyze and respond to, make a judgment . . . about what you just read, and then participate in the conversation about it.” For the English experts in this study, reading, writing, and talking worked together to develop their students’ relationship with disciplinary texts. Implications and Conclusion Although research on teacher beliefs has been backgrounded in favor of research on the effectiveness of practice, to improve the development of disciplinary literacy practices, literacy researchers and educators must know more about the literacy beliefs of disciplinary experts. As a field, when we have a clearer view of how English experts view literacy and develop their students’ literacy practices, literacy educators can then make more informed decisions about how to prepare secondary teacher candidates to develop (and problematize) the frames of mind and approaches that will allow them to help their own students develop a more robust set of English disciplinary literacy practices. Moreover, future research could explore the multidimensional nature of literacy in English. Clearly, literacy is not always and only one thing. By exploring the various dimensions of literacy in English and other disciplines literacy research can provide a more robust view of what it means to construct knowledge in English. Specifically, what dimensions are there, which ones seem most promising for future study, and what is the nature of the relationships among the various dimensions of the English discipline? LITERACY IN THE ENGLISH DISCIPLINE 11 In terms of practice, English educators can draw from the current paper to highlight the various ways of developing a robust reader-text relationship for their students. This could spark conversation about the students’ relationships with the discipline and disciplinary texts. Furthermore, English educators could use this work as a way to begin or extend the discussion about the value of a disciplinary relationships with texts and how students might develop them. As we, as a field, move forward with disciplinary literacy research and practice, Carol Lee’s words seem to echo. “Disciplinary literacy is the civil right of the twenty-first century,” she argues. It ‘provides access to learning in all subject matters and, by so doing, opens up an array of life opportunities for young people” (p.24). LITERACY IN THE ENGLISH DISCIPLINE 12 References Appleman, D. (2000). Critical encounters in high school English: Teaching literary theory to adolescents. New York: Teachers College Press. Bain, R. B. (2005). “They thought the world was flat?” Applying the principles of How People Learn in teaching high school history (pp.179-213). Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. Bain, R. B. (2006). Round up unusual suspects: Facing the authority hidden in the history classroom. Teachers College Record, 108(10), 2080-2114. Bass, H. (2006). What is the role of oral and written language in knowledge generation in mathematics? Toward the improvement of secondary school teaching and learning. Integrating language, literacy, and subject matter. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. Corbin, J., and Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of qualitative research (3rd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage. Grossman, P. L., and Stodolsky, S. S. (1995). Content as context: The role of school subjects in secondary school teaching. Educational Researcher, 24(8), 5-11. Hand, B., Wallace, C., and Yang, E. (2004). Using the science writing heuristic to enhance learning outcomes from laboratory activities in seventh grade science: Quantitative and qualitative aspects. International Journal of Science Education, 26, 131-149. Lee, C. D. (2001). Is October Brown Chinese? A cultural modeling activity system for underachieving students. American Educational Research Journal, 38(1), 97-141. Lee, C.D. (2004). Literacy in the academic disciplines and the needs of adolescent struggling readers. Voices of Urban Education, Winter/Spring, 14-25. LITERACY IN THE ENGLISH DISCIPLINE 13 Lee, C. D., and Spratley, A. (2010). Reading in the disciplines and the challenges of adolescent literacy. New York, NY: Carnegie Corporation. McConachie, S., Hall, M., Resnick, L., Ravi, A. K., Bill, V. L., Bintz, J., and Taylor, J. A. (2006). Task, text, and talk: Literacy for all subjects. Educational Leadership, October, 40-46. McKenna, M. C., and Robinson, R. D. (1990). Content literacy: A definition and implications. Journal of Reading, 34, 184–186. Moje, E. B. (2007). Developing socially just subject-matter instruction: A review of the literature on disciplinary literacy teaching. Review of Research in Education, 31, 1-44. Moses, R. and Cobb, C. E. (2001). Radical equations: Civil rights from Mississippi to the Algebra Project. Boston, MA: Beacon Press. Shanahan, T., and Shanahan, C. (2012). What is disciplinary literacy and why does it matter? Topics in Language Disorders, 32 (1), 7-18. doi: 10.1097/TLD.0b013e318244557a Shanahan, T., and Shanahan, C. and Misischia, C. (2011). Analysis of expert readers in three disciplines: History, mathematics, and chemistry. Journal of Literacy Research 43(4), 393-429. doi: 10.1177/1086296X11424071 Strauss, A. and Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Wineburg, S. S. (1991). On the reading of historical texts: Notes on the breach between school and the academy. American Educational Research Journal, 28(3), 495-519 Wineburg, S. S. (1998). Reading Abraham Lincoln: An expert/expert study in the interpretation of historical texts. Cognitive Science, 22(3), 319-346.