Adoption and single fathers - Democratic Governance & Rights Unit

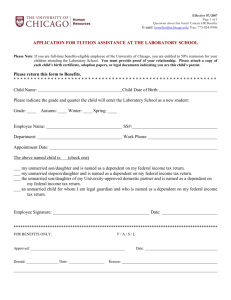

advertisement