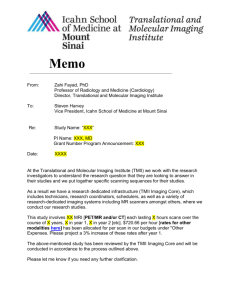

INVESTIGATOR*S BROCHURE For:

advertisement