Latin Sentence Structure: A Beginner's Guide

advertisement

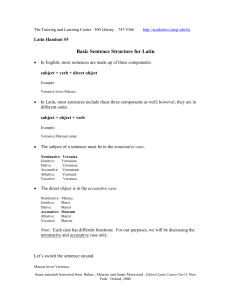

The Tutoring and Learning Center 300 Library 747-5366 http://academics.utep.edu/tlc Latin Handout #5 Basic Sentence Structure for Latin In English, most sentences are made up of three components: subject + verb + direct object Example: Veronica loves Marcus. In Latin, most sentences include these three components as well; however, they are in different order. subject + object + verb Example: Veronica Marcum amat. The subject of a sentence must be in the nominative case. Nominative: Veronica Genitive: Veronicae Dative: Veronicae Accusative: Veronicam Ablative: Veronicā Vocative: Veronica The direct object is in the accusative case. Nominative: Genitive: Dative: Accusative: Ablative: Vocative: Marcus Marci Marcō Marcum Marcō Marcus Note: Each case has different functions. For our purposes, we will be discussing the nominative and accusative case only. Let’s switch the sentence around. Marcus loves Veronica. Some materials borrowed from Balme , Maurice and James Morwoord . Oxford Latin Course Part I. New York: Oxford, 2000. Hint: Marcus = nominative Veronica = accusative. Answer: Marcus Veronicam amat. The verb must agree in number and person (1st, 2nd, 3rd) with the subject. Also, verbs fall under one of 4 conjugations. 1st conjugation (stems in –a) I par-ō You (sing) parā-s He/she para-t We parā-mus You (pl.) parā-tis They para-nt 2nd conjugation (stems in –e) I mone-ō You monē-s He/she mone-t We monē-mus You (pl.) monē-tis They mone-nt 3rd conjugation (stems in consonants) I reg-ō You (sing) reg-is He/she reg-it We reg-imus You (pl) reg-itis They reg-unt 3rd conjugation (stems in –io) I capi-ō You (sing) cap-is He/she cap-it We cap-imus You (pl.) cap-itis They capi-unt 4th conjugation (stems in –i) I audi-ō You (sing) audi-s He/she audi-t We audi-mus You (pl.) audi-tis They audi-unt Some materials borrowed from Balme , Maurice and James Morwoord . Oxford Latin Course Part I. New York: Oxford, 2000. Word order Latin allows for a very flexible word order because of its inflectional syntax. Ordinary prose tended to follow the pattern of Subject, Indirect Object, Direct Object, Adverbial Words or Phrases, Verb (SIDAV). Any extra, though subordinate verbs, are placed before the main verb; for example infinitives. Adjectives and participles usually directly followed nouns, unless they were adjectives of beauty, size, quantity, goodness, or truth, in which case they preceded the noun being modified. Relative clauses were commonly placed after the antecedent which the relative pronoun describes. While these patterns for word order were the most frequent in Classical Latin prose, they are frequently varied; and it is important to recall that there is virtually no evidence surviving that suggests the word order of colloquial Latin (see Vulgar Latin). In poetry, however, word order was often changed for the sake of the meter, for which vowel quantity (short vowels vs. long vowels and diphthongs) and consonant clusters, not rhyme and word stress, governed the patterns. It is, however, important to bear in mind that poets in the Roman world wrote primarily for the ear, not for the eye; many premiered their work in recitation for an audience. Hence, variations in word order served a rhetorical, as well as a metrical purpose; they certainly did not prevent understanding. In Virgil's Eclogues, for example, he writes, Omnia vincit amor, et nos cedamus amori!: Love conquers all, let us yield to love!. The words omnia (all), amor (love) and amori (to love) are thrown into relief by their unusual position in their respective phrases. The meter here is dactylic hexameter, in which Virgil composed The Aeneid, Rome's national epic. The ending of the common Roman name Marcus is different in each of the following examples due to its grammatical usage in that sentence. The ordering in the following sentences would be perfectly correct in Latin and no doubt understood with clarity, despite the fact that in English they are awkward at best and senseless at worst: Marcus ferit Corneliam: Marcus hits Cornelia. (Subject-Verb-Object) Marcus Corneliam ferit: Marcus Cornelia hits. (Subject-Object-Verb) Cornelia dedit Marco donum: Cornelia has given Marcus a gift. (Subject, Verb, Indirect Object, Direct Object) Cornelia Marco donum dedit: Cornelia (to) Marcus a gift has given. (Subject, Indirect Object, Direct Object, Verb) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Latin_grammar#Word_order Some materials borrowed from Balme , Maurice and James Morwoord . Oxford Latin Course Part I. New York: Oxford, 2000. Sentence Structure Although Latin does not have any set sentence structure, due to the ending of nouns telling you what each word means in a sentence, there are some sentences constructions you would want to know about. Subject-Linking Verb-Compliment -These are the simplest types of sentences to work with. They are composed of a Noun, a verb, and usually an adjective. -The noun and verb MUST ALWAYS agree. e.g. (Singular noun/Singular verb -Plural noun/ Plural verb) -Nouns and the compliment MUST AGREE as well, the noun will always be Nominative case, for it is the subject, so the adjective, which must always agree in case, number, and gender will be in the Nominative case. Puer est Romanus - The boy is Roman The boy, puer, is nominative singular Masculine, so your compliment is nominative, singular, masculine. Also, Puer, is singular, thus you use the singular verb, est. Puellae sunt defessae - The girls are tired Plural subject/Plural verb Plural Nom. Fem. subject, Plural. Nom. Fem Compliment. Compound Sentences These are sentences brought together by conjunctions. They can bring together sentences, clauses, and simply words. e.g. Cornelia sedet et legit. Cornelia sits and reads. Notice how et brings together the first sentence, with the word 'read'. Although apparent, conjoined sentences keep the same subject as the first clause. Questions Questions are easily asked within latin, they can either be introduced by interrogative words (Who, what, when etc.) or by adding the enclitic -ne to the end of the first word (usually the verb) of a question e.g. Quid facit Cornelia? - What is Cornelia doing? Estne puer laetus? - Is the boy happy? Also, nonne can be used when you expect "yes" to be the answer. e.g. Nonne cenare vultis? - Surely you want to eat, dont you? (or, more simply, You want to eat, right?) Some materials borrowed from Balme , Maurice and James Morwoord . Oxford Latin Course Part I. New York: Oxford, 2000. Regular Sentence Form The name itself is unfit, due to the many different ways to form sentences and use of passive verbs, deponents, etc. but a basic sentence, for our case, usually consists of a Subject, a verb, a Direct Object, and an ablative. e.g. Sextus vexat Corneliam in horto semper. - Sextus is always annoying Cornelia in the garden http://www.learnlatinonlinefree.com/sentence_structure.php Some materials borrowed from Balme , Maurice and James Morwoord . Oxford Latin Course Part I. New York: Oxford, 2000. Some materials borrowed from Balme , Maurice and James Morwoord . Oxford Latin Course Part I. New York: Oxford, 2000.