References

advertisement

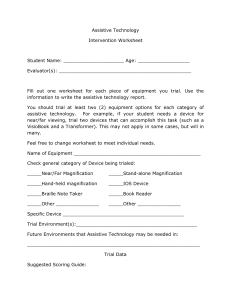

Determining Children’s Assistive Technology Needs through Video Conferencing Assessments Debra Bauder University of Louisville United States debra.bauder@louisville.edu Abstract: Based upon current practices, state-of-the-art assistive technology assessment systems are not widely developed or implemented in rural areas. Children with disabilities have major problems in accessing assistive technology that meets their needs. In addition, the availability of trained professionals that can diagnose the nature of a child’s assistive technology needs and identify the technology that will best suit their situation is also a dilemma. The ATVC (assistive technology via videoconferencing) Model uses distance-based videoconferencing technology capabilities in assessing the assistive technology needs of students living in rural areas. This model capitalized on the expertise of assistive technology experts that guide local school personnel in the actual assessment process via videoconferencing connections for a distance-based diagnosis and identification of possible technologies that fit the students’ need. Introduction We are only beginning to understand the impact that technology has on children’s ability to learn and to achieve educational outcomes. This is especially true for children with disabilities. Children with disabilities frequently experience obstacles in meeting the demands of their environment. The use of technology, including assistive and adaptive devices, can improve their level of functioning (Blackhurst, 1997; Dell, Newton, & Petroff, 2012; Lewis, 1993; Michaels & McDermott, 2003; Wojcik, Peterson-Karlan, & Parette, 2004). This is especially true given the push of providing general access to the curriculum for all children receiving specially designed instruction. It is also important that students are provided meaningful access to curriculum. In order for this access to be achieved, the child’s program should include the supports, modifications and accommodations that can ensure that the child’s educational goals are achievable (Molloy & Baskin, 1994/1995; Orkwis & McLane, 1998; Pugach & Warger, 2001). To provide an environment for children with disabilities, the availability and implementation of assistive technology needs to exist (Bauder, 1999; Bausch & Ault, 2008; Dell, Newton, & Petroff, 2012). To be successful in meeting the needs of students, an assistive technology process must be designed based upon the best practices including “a) employing technology as a tool to facilitate the achievement of educational goals; b) utilizing environmentally based assessment procedures to assist in the selection of appropriate assistive equipment and c) promoting interactions with non-disabled peers in a natural environments” (ASHA, 1996, p. 14). Ideally, the selection of assistive technology should be based on individual student needs, not on equipment availability (Bauder, 1999). Furthermore, It is agreed that the success experience by students with disabilities when using AT is related directly to the AT knowledge, skills and training of teachers (Michaels & McDermott, 2003: Wojcik, Peterson-Karlan, & Parette, 2004). Integrated assessment procedures are an important aspect of the assistive technology identification. These procedures are a two-fold process. The first process involves the initial identification of individual’s needs. Secondly, an assistive technology assessment process should be an on-going facet of the education program (Lynch & Reed, 1999). This on-going process is used to evaluate the effectiveness and fine-tune the use of assistive equipment. In addition, both processes should include a fluid multidisciplinary team, (whose members change depending on the student’s needs, to assess and prescribe technology) (ASHA, 1996). Additionally, as a result of the assessment and identification of needs, technology should be integrated where appropriate and as needed, across all learning environments of the individual. This AT process is designed through the process of assessing a child’s needs, goals, and skills; using these results to determine the necessary characteristics that an assistive technology system must have; conceiving of, and planning for that individual; delivery and training in device use; and following up to evaluate success (Chambers, 1997). Videoconferencing Technology State-of-the-art assistive technology delivery systems are not widely developed or implemented, especially in rural areas. The multidisciplinary personnel needed to provide service delivery is also limited, therefore, children are not necessarily afforded the assistive technology needed to enhance, promote or provide educational progress, access to general curriculum and participate in school reform efforts. However, recent telecommunications developments, particularly integrated voice, video and data systems, as well as satellite and compression technologies, have made distance education formats a viable alternative to improving access to educational opportunities for learners of all ages, at all levels and in diverse environments (Bilton-Ward, 1997; Kearsley, 2000). Videoconferencing is a powerful information-sharing medium and an innovative way to convey ideas, and share information to groups of people. This is accomplished through the transmission of digital voice conversations and video pictures through the Internet (Bilton-Ward, 1997; Petty, Harrison, & Treviranus, 1999). To start an Internet videoconference, both parties first need to be on-line with multimedia-equipped computers i.e., powerful computer, speakers, microphone, and video or mini camera. Each person can see and speak into their microphone to record and transmit their voice as digital data through the Internet. In order to have effective transmission it is recommended that a T1 or a DSL line instead of dial-up Internet access is utilized (Lehman & Dewey, 1998). Videoconferencing provides instant communication, and allows the ability of individuals to meet face to face regardless of distance. It also allows facilitating learning between remote classrooms and educational centers by providing immediate access to specialist from remote locations, while maximizing human resources (Burge & Roberts, 1993; Petty, Harrison, & Treviranus, 1999). Advantages and uses of videoconferencing include: is a viable, effective and efficient medium for a number of reasons such as; access to many different types experts working at other locations, personnel in remote or dispersed locations can access to primary site personnel, increased professional and education training opportunities (Brody, 1995; Burge & Roberts, 1993). Conducting Assistive Technology Assessments The ATVC (assistive technology via videoconferencing) Model addressed rural access to multidisciplinary assistive technology evaluation and technical assistance from trained professionals by using distance-based interactive technologies to conduct distance-based assistive technology assessments and provides technical assistance. While distance-based diagnosis and treatment services have been utilized in the medical field for a number of years (e.g. telemedicine), the application of current distance based interactive technology for educational evaluation and assistance has remained somewhat unexplored. The video conferencing tools used to assess the students were accomplished in three primary modes: video phone using plain old telephone (POTS) systems, a compressed video system using three ISDN lines, and/or the Internet/Web utilizing various software and camera technologies. Assessment Procedures The procedures for conducting the assistive technology assessment comprised of an initial referral, completion of an AT screening form, and videoconference meeting with the local education team working with the respective student. This videoconference between the LEA and AT expert team was important to further clarify the student needs based upon the background information that was previously collected about the student. The assessment protocol was a basic framework in which activities were developed for each individual assessed. Local participants participated in videoconference rehearsal of the assessment prior to each distance-based assessment. Also, an assessment kit tailored to each child’s individual AT assessment needs was sent to each team leader at least one week prior to the assessment in order for the local team to familiarize themselves with the equipment that was to be used during the assessment. The actual assessment included a videoconference link and the expert AT team would watch and guide the local school team members in conducting the assessment. The assessment protocol was used and developed as a script that the LEA team used during the assessment process. The LEA team could also ask questions or comment as the assessment was being conducted. The AT expert team and the local team debriefed after each evaluation, Their discussion reviewed the assessment and the observations that all personnel identified during the process. This information was used to provide critical issues and information for the assessment report. The provision of professional development training was an outcome of each assessment. Once the AT needs of each child was determined, a distance-based training was developed for each local school team. District personnel were involved in the selection and in the development of each training event. The majority of the professional development training was provided through a compressed videoconferencing network. However, there were several professional development trainings conducted via the videophone. At the end of each training, school personnel was asked to submit a training event evaluation form. Overall, training was rated very helpful to the implementation of the overall AT program. In addition, products and materials were developed to individualize the professional development training. For example, customized communication boards and Intellikeys ™ overlays were developed for numerous students. These overlays were designed specifically with the student that received the videoconferencing based AT assessment. The Study Participants Approximately 50 students were initially referred participated in using videoconferencing assessment model. This number represents individuals that the local school districts. The 50 referrals were screened and narrowed to 30 participants. All 30 were included in the evaluation process; however, only 28 were ultimately evaluated due to maturation effects. For example, medical complications developed that prevented two students from being assessed. The participants represented a wide variety of characteristics and needs. This was done to determine the utility of the videoconference approach to live AT assessment based on disability characteristics. Further, each of the participants was broadly matched on similar characteristics and randomly assigned to use a compressed video assessment, videophone, or videoconference via web (SKYPE, Webcam). This process was implemented to determine effectiveness of the various videoconference technologies for performing distance-based AT assessment. The demographic variables that represented the 28 rural evaluations included, nine participants at the elementary level, nine participants at the middle school level and 10 participants at the high-school level. The breakdown of diagnostic categories of the participants is found in Table 1. Table 1. Diagnostic categories of participants Disability Category N Disability Category N Physical disability Speech impairment Learning Disability Visual Impairment Functional Mental Disability Hearing Impairment 7 4 3 11 2 1 ADHD Autism Developmentally Delayed Cerebral Palsy Down’s Syndrome 5 5 3 1 1 The AT assessment needs of the 28 rural students were further defined: 16 having academic needs, 13 having environmental needs, and 20 with communication issues. It should be noted that some students had overlapping needs. Findings Evaluation activities consisted of using rubrics, questionnaires and various statistical analyses to understand the various nuances of the study activities. Questionnaires were used to evaluate the satisfactoriness of the evaluation. This was accomplished by having both the rural local school team evaluate the process along with the AT experts members responding to an equivalent questionnaire. Local Education Agency Participants Twenty-eight distance-based assistive technology assessments were conducted. All LEA respondents (n=48) indicated that the directions provided by the AT expert team were adequate for the local education agency (LEA) team to complete the task of implementing and/or securing the AT devices. Some initial concerns were expressed about the viability of the process, however satisfaction was expressed by all of LEA participant team members. Eighty percent of the respondents from the LEA team members indicated intent to follow through with the recommendations. As a result of the assessments it was found that conducting videoconferencing based AT assessment was a viable method of conducting distance-based assessments. Furthermore, many local team member have indicated that they are eager to assist in furthering the use of AT for their students as a result of participating in the distance based assessments. Additionally, local school district team members expressed that by participating in this type of assessment they improved their local interdisciplinary collaboration efforts and increased communication among local AT team members. Student Impact The impact on students can be looked at, quite literally, as what can the student do that the student could not do before the initiation of this process. Other variables include whether the assessments were utilized in the development of an updated IEP and whether programs were developed that supported that IEP. Further, changes in the student’s performance on other indicators such as test scores, standardized assessments, improvement in portfolios and performance in everyday school activities such as homework, group participation, reading or writing activities were analyzed. All of these variables lead to a perceived understanding of the impact of videoconferencing assessment on the student recipient. Data analysis indicates that video conferencing assessment reports have been applied in most of the participating students classrooms. Reviewing the data, over 80% (22 of the 28) of the students had the suggested services or products included or projected to be included in the student’s IEP or daily activities. Of those students that have had an IEP Team meeting (Admissions and Release Committee-ARC) and have had a discussion of the AT assessment report, only one student’s IEP did not include the recommendation from the AT assessment. This was due to the fact that there was another more recent AT assessment and the ARC chose to follow the suggestions of the more recent assessment. Of the students that have received some aspect of the recommended AT services/products, the LEA reports that eight of the students felt comfortable working with the recommended item. Additionally, the LEA representative indicated that all of the students (n = 22) who have received the AT assessment recommended devices/services were integrating the AT into the classroom. The LEA representatives reported that the majority (20) of the students had integrated the AT across curriculum; three integrated the AT across the home, school and community, and three across various staff. Of the 20 students that have benefitted from having the recommended AT assessments services/devices, the LEA representative reported that 10 of the students have had average or above average benefits. However, one student appeared to be experiencing no benefits of the recommended assistive technology. Conclusions The ATVC Model was an effort to provide children with disabilities better means of accessing technologies that would enable them to achieve outcomes expected of all students, such as greater independence and productivity especially in rural settings. This effort was achieved not only through using video-conferencing and Internet technologies to provide functional assistive technology assessments, but also a) assists school personnel in determining and implementing assistive technology devices and services and b) conducting professional development for school personnel through distance based technology avenues. This model of conducting distance based AT assessments had many positive outcomes. First and foremost, the viability of conducting distance based videoconferencing AT assessments has been established. Students living in rural areas can be provided AT assessments without having to travel long distances. Additionally, it has been realized that using this technology not only allows for reliable AT assessments, but also an impetus for developing strong school team approaches. Many local school team members indicated that they are now working more closely, and as a result, the identified students have a more cohesive individualized education plan. Through this model, procedures, the development of local team members in understanding and using the technology has been of great benefit. Many local team members did not use technology or recommend the use of technology for their students because of their own lack of knowledge and training. Through this model of AT assessment, local team members became stakeholders. As a result of participating in the assessment process, the team became more acquainted with the technology, thereby more comfortable in using the technology. As a result, there was a greater likelihood that students would then be the beneficiaries of recommended AT. The provision of professional development workshops increased or strengthened both local school personnel and parents on how to use the technology. The workshops were well received and it is believed that they further increased everyone’s comfort level and expertise. Training school personnel and parents also helped them to understand the benefits of using the AT. The AT videoconferencing model was successful in creating a system in which distance based AT assessments could be accomplished. It was believed that using this technology, in itself, holds great promise to students that are not afforded AT assessment because of lack of qualified local school personnel. It is through this technology, that AT specialists can assist local school personnel in the identification of implementation of AT for children. It is also believed that through this process, children with disabilities might be afforded the AT that could provide them with greater access to the curriculum. As a result, children with disabilities would be able to be more successful in reaching their educational goals. References ASHA (1996). Technology in the classroom: Education module. Rockville, MD: American Speech Hearing Association, 1996. Bouck, E. C., Shurr, J. C., Tom, K., Jasper, A. D., Bassette, L., Miller, B., & Flanagan, S. M. (2012). Fix It With TAPE: Repurposing Technology to Be Assistive Technology for Students With High-Incidence Disabilities. Preventing School Failure, 56(2), 121-128. doi:10.1080/1045988X.2011.603396 Bausch, M. E., & Ault, M. J. (2008). Assistive technology implementation plan: A tool for improving outcomes. Teaching Exceptional Children, 41 (1), 6–14. Bauder, D. K (1999). The use of assistive technology and the assistive technology training needs of special education teachers in Kentucky schools. (Doctoral Dissertation: University of Kentucky, 1999). Dissertation Abstracts International, 60, 12A , 1999, 4378. Bilton-Ward, A. C. (1997). Virtual teaching: An educator’s guide. Waco, TX: CORD Communications, 1997. Blackhurst, A. E. (1997). Perspectives on technology in special education. Teaching Exceptional Children, 29(5), 41-48. Blackhurst, A. E., & Shuping, M.B. (1990). A philosophy for the use of technology in special education: Technology and media back-to-school guide. Reston, VA: Council for Exceptional Children, 1990. Burge, E. J., & Roberts, J. M. (1993). Classrooms with a difference: A practical guide to the use of conferencing technologies. Toronto: The Ontario Institute for Studies in Education. Brody, P. J. (1995). Technology planning and management handbook: A guide for school district educational technology leaders. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Educational Technology. Chambers, A. C. (1997). Has technology been considered? A guide for IEP teams. Albuquerque, NM: Council of Administrators in Special Education, 1997. Bühler, C., Engelen, J., Emiliani, P., Stephanidis, C., & Vanderheiden, G. (2011). Technology and inclusion - Past, present and foreseeable future. Technology & Disability, 23(3), 101-114. Dell, A., Newton, D., & Petroff, G. (2012). Assistive technology in the classroom: Enhancing the school experiences of students with disabilities, (2nd ed.) Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Dove, M. K. (2012). Advancements in Assistive Technology and AT Laws for the Disabled. Delta Kappa Gamma Bulletin, 78(4), 23-29. Hällgren, M. M., Nygård, L. L., & Kottorp, A. A. (2011). Technology and everyday functioning in people with intellectual disabilities: a Rasch analysis of the Everyday Technology Use Questionnaire (ETUQ). Journal Of Intellectual Disability Research, 55(6), 610-620. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2788.2011.01419.x Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Disability in America; Field MJ, Jette AM, editors. The Future of Disability in America. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2007. 7, Assistive and Mainstream Technologies for People with Disabilities. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK11418/ Kearsley, G. (2000). Online education: Learning and teaching in cyberspace. (Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing. Lewis, R. B. (1993). Special education technology: Classroom applications. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing. Lynch, J. L., & Reed, P. (1999). Using an assistive technology checklist to facilitate consideration, assessment and planning. CSUN's Fourteenth Annual International Conference Technology and Persons with Disabilities Proceedings, Los Angeles, CA. Retrieved on August 2, 2002 at http://www-cod.csun.edu/conf/1999/ proceedings/session0041.htm. Lehman, R., & Dewey, B. (1998). Videoconferencing training beyond the keypad: Using the interactive potential. Conference Proceedings ITCA Expo 1998, Philadelphia, PA. Retrieved on September 1, 2002 at http:www.uwex.edu/disted/training.htm. Mavrou, K. (2011). Assistive technology as an emerging policy and practice: Processes, challenges and future directions. Technology & Disability, 23(1), 41-52. Michaels, C. A. & McDermott, J. (2003). Assistive technology integration in special education teacher preparation: Program coordinators’ perceptions of current attainment and importance. Journal of Special Education Technology, 18(3), 29-41. Molloy, P., & Baskin, B. (1994/1995). The challenge of educational technology for students with multiple impairments in the classroom. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 23(1), 75-85. Orkwis, R., & McLane, K. (1998, Summer). A curriculum every student can use: Design principles for student access. Reston, VA: ERIC/OSEP Special Project, Council for Exceptional Children. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 423654) Petty, L., Harrison, L., & Treviranus, J. (Feb/March 1999). Distance education: Tools and applications in assistive technology. Henderson, MN: Closing the Gap. Retrieved on October 1, 2002 at http://www.closingthegap.com/cgi-bin/lib/libDsply.pl?a=1179&b=2&c=2. Pugach, M. C., & Warger, C. L. (2001). Curriculum matters: Raising expectations for students with disabilities. Remedial and Special Education, 22(4), 194-196. Lee, H., & Templeton, R. (2008). Ensuring Equal Access to Technology: Providing Assistive Technology for Students With Disabilities. Theory Into Practice, 47(3), 212-219. doi:10.1080/00405840802153874 Reichle, J. (2011). Evaluating Assistive Technology in the Education of Persons with Severe Disabilities. Journal Of Behavioral Education, 20(1), 77-85. Wojcik, B. W., Peterson-Karlan, G., Watts, E. H., & Parette, P. (2004). Assistive technology outcomes in a teacher education curriculum. Assistive Technology Outcomes and Benefits, 1, 21-32