American Military History, Topic 8: World War II and FDR*s Fireside

advertisement

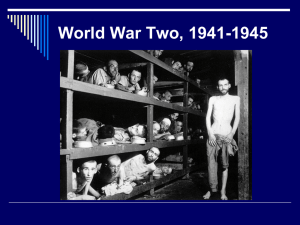

American Military History, Topic 8: World War II and FDR’s Fireside Chat (12 June 1944) Background: Twenty years after the Great War, an even larger and more destructive global conflict, and the last Congress-declared war in American history—World War II (1939-1945)— scarred the earth and effected deep change. Sixty million people died in World War II—six times more than in the carnage of the “War to End All Wars”—and over half of them were civilians. The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics lost 20-25 million, China lost 15 million, Poland lost six million, Germany lost four million, Japan lost two million, Great Britain lost 450,000, and the United States lost 400,000, making World War II the second deadliest war in American history (behind the American Civil War). Joseph Stalin murdered five to ten million political enemies in the USSR, and Adolph Hitler extinguished the lives of six million Jews throughout Europe. German aggression in Austria (1938), Czechoslovakia (1938-39), and Poland (1939, which brought France and Britain into the war against Germany) in defiance of the vindictive Treaty of Versailles (1919), and Japanese aggression in China (1937, which began the Sino-Japanese War), had begun the war as a ruthless imperialist conquest. By June 1941, the conflict pitted the Axis powers (Germany, Italy, and Japan) against the Allied powers (Britain and Russia; France had fallen), and, by August 1945, following four years of invaluable American military participation in two theaters of operation (the European and Pacific), the Allies would defeat Germany and Japan, and the United States would emerge as the world’s preeminent economic and military power—and the leader of the free world—which it would remain for the next seventy years. Between September 1939 and December 1941, while France fell and Britain and Russia fought alone against Germany, Franklin D. Roosevelt made the United States into the “Arsenal of Democracy.” Though Roosevelt promised that America would “remain a neutral nation” in the European conflict, he believed neutrality allowed the U. S. to provide armaments to the Allies. In September 1939, he asked Congress to revise the Neutrality Acts, which forbade the U. S. to sell arms to belligerent nations. Though isolationists protested, Congress passed revisions that allowed nations at war to purchase arms on a cash-and-carry basis. In September 1940, Roosevelt encouraged Congress to pass the Burke-Wadsworth Act to begin the first peacetime draft in American history, and, in December 1940, Roosevelt asked America to become the “great arsenal of democracy” in two ways: by providing war materials to Britain (which fought alone at that point) and by building up American military stores in preparation for a defense of the U. S. and possible entry into the war. In January 1941, Roosevelt asserted that “the future and the safety of our country and of our democracy are overwhelmingly involved in events far beyond our borders” and said that he looked forward to a world “founded upon four essential human freedoms”: freedom of speech and expression, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear, which would become aims of the international peacekeeping and human rights organization—the United Nations—for which he pushed prior to his death in 1945. To further these ends by his support of virtually bankrupt Britain, in March 1941, Roosevelt championed the Lend-Lease Act, which allowed the U. S. to lend or lease for the promise of future reimbursement—instead of just sell—armaments to any nation deemed “vital American Military History, Topic 8: World War II and FDR’s Fireside Chat (12 June 1944) to the defense” of America. Following Hitler’s invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, Roosevelt extended Lend-Lease aid to the USSR. As Roosevelt continued to claim that America’s fate was tied to the fate of the Allies, he began sending American ships to escort the British vessels that transported Lend-Lease supplies to Britain. In April 1941, American and British military officers met secretly to discuss possible joint strategy, and, in August 1941, Roosevelt and British prime minister Winston Churchill signed the Atlantic Charter, which asserted principles and objectives for a “better future for the world”, including the “final destruction of the Nazi tyranny.” American entry into the war looked inevitable. In the fall of 1941, Roosevelt ordered the American navy to fire at German submarines, armed American merchant ships, and directed American vessels to sail into war zones to reach Allied ports, which effectively began a naval war against Germany. After Roosevelt’s cancellation of a longstanding commercial treaty with Japan, freezing of Japanese assets in the U. S., and creation of a complete trade embargo led to a surprise Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, which resulted in 3,000 American casualties, Congress declared war on Japan (8 December 1941) and Germany and Italy (11 December 1941). No other single event would unify the American people behind the war effort, a goal for which Roosevelt had worked for two years, more than the tragedy at Pearl Harbor. For most of the next four years, the U. S. would lend decisive military aid to the Allied war effort against Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy in Europe and North Africa and fight the Japanese in the Pacific virtually alone. Over 16.4 million Americans joined the armed forces— though only 34 percent of the men who served saw combat—and, between 1942 and 1945, theirs would be the sacrifices of the so-called “Greatest Generation” of Americans. With Britain and Russia on the brink of defeat and the Japanese navy steamrolling opposition in the Pacific, beginning in the summer of 1942, the American navy scored a tremendous victory at Midway (June 1942), which established Allied control of the central Pacific, and then won a savage six-month affair at Guadalcanal (August 1942-February 1943), which asserted Allied dominance in the southern Pacific. Between November 1942 and May 1943, Anglo-American forces fought their way across North Africa to victory at Tunis, Tunisia, which secured Africa for the Allies. In the summer of 1943, Anglo-American troops invaded Italy, capturing Sicily and forcing Benito Mussolini’s government to collapse, before running into a German defensive wall south of Rome. After harsh battles at Monte Cassino (May 1943) and Anzio (January 1944), the Allies finally liberated the Italian capital on 4 June 1944. Two days later, on D-Day, three million Allied troops, and the largest number of naval vessels and armaments ever assembled for an invasion, crossed the English Channel to invade German-occupied France at Normandy. Within a week, the Allies had secured the Normandy coast, and, on 25 August 1944, the Allies, with Charles de Gaulle’s exiled Free French forces in the lead, liberated Paris. By mid-September, the Germans had abandoned the great majority of France and Belgium and, following the Battle of the Bulge (December 1944-January 1945), in which Hitler’s desperate counteroffensive failed, they retreated back to Germany. On 8 May 1945, American Military History, Topic 8: World War II and FDR’s Fireside Chat (12 June 1944) after being encircled by Allied forces and learning of Hitler’s suicide, Germany surrendered unconditionally. In the Pacific, brutal combat in the Mariana Islands (June 1944), the Battle of Leyte Gulf (October 1944, the largest naval engagement in history, which crippled the Japanese navy), and costly, to-the-last-man battles at Iwo Jima and Okinawa (February-March 1945, April-June 1945) led to the firebombing of Tokyo and, ultimately, to the introduction of atomic warfare to the world. On August 6, the U. S. dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima and, three days later, another on Nagasaki, killing over 200,000 Japanese civilians. Emperor Hirohito called for surrender on August 14, and, on 2 September 1945, Japanese surrender became official. President Harry Truman, who had succeeded Roosevelt upon his death on 12 April 1945, confidently claimed that the decision to drop the bomb had saved lives and ended the war quickly; others have not been so sure. Had Truman dropped the bomb to gain the upper hand in the initial stages of the cold, diplomatic war with the USSR that he anticipated? Would Japan have surrendered shortly even if atomic force had not been employed? Would Truman have used such horrific technology against a European foe? These are questions for the ages. While war raged in Europe and the Pacific, the American home front changed considerably. The war—not Roosevelt’s New Deal—brought the U. S. out of the Great Depression. Government spending had a multiplier effect on the economy, as contracts with industry rapidly increased the gross national product, and the rise in production provided full employment. After 1940, the American economy enjoyed a prolonged boom, and industrial production increased fourfold. By 1944, the U. S. produced more than twice as much as all of the Axis powers combined. A huge consumer boom, matched by a baby boom, was the result of such widespread prosperity, and, while Europe and Asia, and much of North Africa and the Pacific, were in shambles, the U. S. flourished. By the end of the war, America had 6 percent of the world’s population and over 50 percent of the world’s wealth, making it, by far, the richest nation on earth. Coupled with the country’s rise to the most powerful military nation in history, this mind-boggling wealth profoundly changed America’s role in the world, allowing its leaders to make it a global powerbroker and exporter of freedom for the next seven decades. World War II also saw the number of women in the workforce increase by 60 percent. By 1945, women were one-third of all paid American workers. Most of them were married and older than women who had previously entered the workforce. Many of them had children. Though some of them became “Rosie the Riveter” and worked at industrial jobs previously reserved for men, most were “Government Girls” and worked as clerks, secretaries, and typists. One hundred forty thousand women also volunteered for the Women’s Army Corps, and 100,000 offered their services to the Navy WAVES (Women Accepted for Voluntary Emergency Service). Women who maintained the traditional gender role of homemaker during the war had even more to do, as wartime shortages led to rationing, collecting and saving scraps and metals, planting “victory gardens”, and buying war bonds. African Americans fought for the “Double V”—victory against the enemy abroad and racial discrimination at home—throughout the war. By 1944, the number of blacks in the army soared from 5,000 (in 1940) to 700,000, American Military History, Topic 8: World War II and FDR’s Fireside Chat (12 June 1944) with 187,000 more in the other branches of the military. They fought mostly in segregated units and were overwhelmingly excluded from the best-paying jobs in the defense industry, despite protests that “a Jim Crow army cannot fight for a free world.” Under intense pressure from civil rights leaders, Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802 (1941), which created the Fair Employment Practices Commission to ensure that blacks and women received the same pay as white men for doing the same work. Though the order addressed de jure (in law) discrimination, it was almost impossible to remedy de facto (in practice) discrimination, and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) mobilized mass popular resistance to the racial discrimination that continued in the defense industry and beyond. Perhaps more than any other group, Japanese Americans experienced the greatest changes during the war. In 1942, Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 excluded over 100,000 of them from “military areas” in the West and suspended their civil rights. Both first-generation Japanese in America (Issei) and second-generation Japanese-American citizens (Nisei)—regardless of their past demonstrations of loyalty—were forced to leave their property and were shipped to “relocation centers” in western mountains and deserts to become “Americanized.” Ten internment camps in seven states, with barbed wire and armed guards surrounding them, housed the exiles in cramped wooden barracks, where entire families lived in one room only. Japanese Americans lost $500 million in property as a result of internment. In 1944, the Supreme Court ruled that relocation was permissible but barred “loyal” citizens from being interned anymore. By the end of 1944, most of the relocated Japanese Americans had been allowed to return to the West Coast—but they faced intense persecution upon their arrival. Was the internment program necessary to protect the American war effort from sabotage—or was it an unnecessary manifestation of racism? The debate still rages today. Nevertheless, after securing victory in Europe and the Pacific, American soldiers came home to a changed nation. As poet Archibald MacLeish understood in 1943, “This war is not a war only, but an end and a beginning—an end to things known and a beginning of things unknown.” The seeds of change that the war planted in American society, culture, politics, and economics have grown and matured over the past seventy years, and opinions vary widely as to whether the nation has become more or less “American” since the conflict: an event that historian Alan Brinkley argues “changed the world as profoundly as any event of the twentieth century, perhaps of any century.” Questions to Consider as You Read: According to FDR, what is the role of the American home front in World War II? What does Roosevelt say about American progress in the Pacific against Japan? What does Roosevelt say about American progress in Europe against Germany? Research: Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Fireside Chat (12 June 1944) As you read, don’t forget to mark and annotate main ideas, key terms, confusing concepts, unknown vocabulary, cause/effect relationships, examples, etc. American Military History, Topic 8: World War II and FDR’s Fireside Chat (12 June 1944) It goes almost without saying that we must continue to forge the weapons of victory—the hundreds of thousands of items, large and small, essential to the waging of the war. This has been the major task from the very start, and it is still a major task. This is the very worst time for any war worker to think of leaving his machine or to look for a peacetime job…. And it goes almost without saying, too, that we must continue to provide our Government with the funds necessary for waging war not only by the payment of taxes—which, after all, is an obligation of American citizenship—but also by the purchase of war bonds—an act of free choice which every citizen has to make for himself under the guidance of his own conscience…. Although there are now approximately sixty-seven million persons who have or earn some form of income, eightyone million persons or their children have already bought war bonds. They have bought more than six hundred million individual bonds. Their purchases have totaled more than thirty-two billion dollars. These are the purchases of individual men, women, and children…. There is a direct connection between the bonds you have bought and the stream of men and equipment now rushing over the English Channel for the liberation of Europe. There is a direct connection between your bonds and every part of this global war today…. While I know that the chief interest tonight is centered on the English Channel and on the beaches and farms and the cities of Normandy, we should not lose sight of the fact that our armed forces are engaged on other battlefronts all over the world, and that no one front can be considered alone without its proper relation to all…. We are on the offensive all over the world—bringing the attack to our enemies. In the Pacific, by relentless submarine and naval attacks, and amphibious thrusts, and ever-mounting air attacks, we have deprived the Japs of the power to check the momentum of our ever-growing and ever-advancing military forces. We have reduced the Japs' shipping by more than three million tons. We have overcome their original advantage in the air. We have cut off from a return to the homeland tens of thousands of beleaguered Japanese troops who now face starvation or ultimate surrender. And we have cut down their naval strength, so that for many months they have avoided all risk of encounter with our naval forces. True, we still have a long way to go to Tokyo. But, carrying out our original strategy of eliminating our European enemy first and then turning all our strength to the Pacific, we can force the Japanese to unconditional surrender or to national suicide much more rapidly than has been thought possible. Turning now to our enemy who is first on the list for destruction—Germany has her back against the wall—in fact three walls at once! In the south—we have broken the German hold on central Italy. On June 4, the city of Rome fell to the Allied armies. And allowing the enemy no respite, the Allies are now pressing hard on the heels of the Germans as they retreat northwards in ever-growing confusion. On the east—our gallant Soviet allies have driven the enemy back from the lands which were invaded three years ago. The great Soviet armies are now initiating crushing blows. Overhead vast Allied air fleets of bombers and fighters have been waging a bitter air war over Germany and Western Europe. They have had two major objectives: to destroy German war industries which maintain the German armies and air American Military History, Topic 8: World War II and FDR’s Fireside Chat (12 June 1944) forces; and to shoot the German Luftwaffe out of the air. As a result, German production has been whittled down continuously, and the German fighter forces now have only a fraction of their former power. This great air campaign, strategic and tactical, is going to continue—with increasing power. And on the west—the hammer blow which struck the coast of France last Tuesday morning, less than a week ago, was the culmination of many months of careful planning and strenuous preparation. Millions of tons of weapons and supplies, and hundreds of thousands of men assembled in England, are now being poured into the great battle in Europe…. We have broken through their supposedly impregnable wall in northern France…. Americans have all worked together to make this day possible.1 Notebook Questions: Reason and Record • According to FDR, what is the role of the American home front in World War II? • What does Roosevelt say about American progress in the Pacific against Japan? • What does Roosevelt say about American progress in Europe against Germany? Notebook Questions: Relate and Record • How does the document relate to FACE Principle #7: The Christian Principle of American Political Union: “Internal agreement or unity, which is invisible, produces an external union, which is visible in the spheres of government, economics, and home and community life. Before two or more individuals can act effectively together, they must first be united in spirit in their purposes and convictions”? 1 SOURCE: Roosevelt, Franklin D.. Fireside Chat (12 June 1944). en.wikisource.org. Accessed 9 June 2011. American Military History, Topic 8: World War II and FDR’s Fireside Chat (12 June 1944) • How does the document relate to Alma 61:9-15? Record Activity: Multiple Choice Comprehension Check 1. Background: All of the following are true about World War II (1939-1945) except which one? a. It was even larger and more destructive than World War I. b. Civilians accounted for over half of all of the deaths of World War II. c. It remains the last Congress-declared war in American history (through August 2011). d. German and Japanese aggressions began the war as a ruthless imperialist conquest. e. At one time or another in the war, the Axis powers consisted of Germany, Italy, and/or Japan, while the Allied powers consisted of Britain, France, Russia, and/or the United States. f. The United States emerged from World War II as the world’s preeminent economic and military power—and the leader of the free world—which it would remain for the next seventy years. g. As the “Arsenal of Democracy”, the U. S. fought Germany in bloody campaigns in France and Britain between 1939 and 1941. 2. Background: Which of the following lists contains correctly matched names and descriptions? a. Iwo Jima and Okinawa: 1941, declaration of war; Leyte Gulf: 1942, control of the central Pacific; Hiroshima and Nagasaki: 1943, secured Africa; Battle of the Bulge: 1944, secured the Western Front (west of Germany); Midway: 1944, the largest naval engagement in history; Rome and Paris: 1944-45, desperate German counteroffensive; Pearl Harbor: 1945, to-the-last-man combat; Tunis: 1945, atomic endgame b. Midway: 1941, declaration of war; Pearl Harbor: 1942, control of the central Pacific; Leyte Gulf: 1943, secured Africa; Hiroshima and Nagasaki: 1944, secured the Western Front (west of Germany); Tunis: 1944, the largest naval engagement in history; Iwo Jima and Okinawa: 1944-45, desperate German counteroffensive; Battle of the Bulge: 1945, to-the-last-man combat; Rome and Paris: 1945, atomic endgame American Military History, Topic 8: World War II and FDR’s Fireside Chat (12 June 1944) c. Pearl Harbor: 1941, declaration of war; Midway: 1942, control of the central Pacific; Tunis: 1943, secured Africa; Rome and Paris: 1944, secured the Western Front (west of Germany); Leyte Gulf: 1944, the largest naval engagement in history; Battle of the Bulge: 1944-45, desperate German counteroffensive; Iwo Jima and Okinawa: 1945, to-the-last-man combat; Hiroshima and Nagasaki: 1945, atomic endgame d. Rome and Paris: 1941, declaration of war; Hiroshima and Nagasaki: 1942, control of central Pacific; Iwo Jima and Okinawa: 1943, secured Africa; Pearl Harbor: 1944, secured the Western Front (west of Germany); Battle of the Bulge: 1944, the largest naval engagement in history; Midway: 1944-45, desperate German counteroffensive; Tunis: 1945, to-the-last-man combat; Leyte Gulf: 1945, atomic endgame 3. Source: In his fireside chat, FDR says all of the following about the American home front except which one? a. The home front is needed to forge weapons of war. b. Workers on the home front are needed in the defense industry. c. Taxes from the home front are needed to fund the war. d. The purchase of war bonds on the home front is needed to fund the war. e. There is a direct connection between a supportive home front and the successful liberation of Europe. f. There is a direct connection between the war bonds of American men, women, and children and every part of the global war. g. Government spending, women in the workforce, African Americans in defenseindustry jobs, and Japanese internment camps are necessary parts of protecting the home front. h. Americans have all worked together to make the successes of D-Day possible.