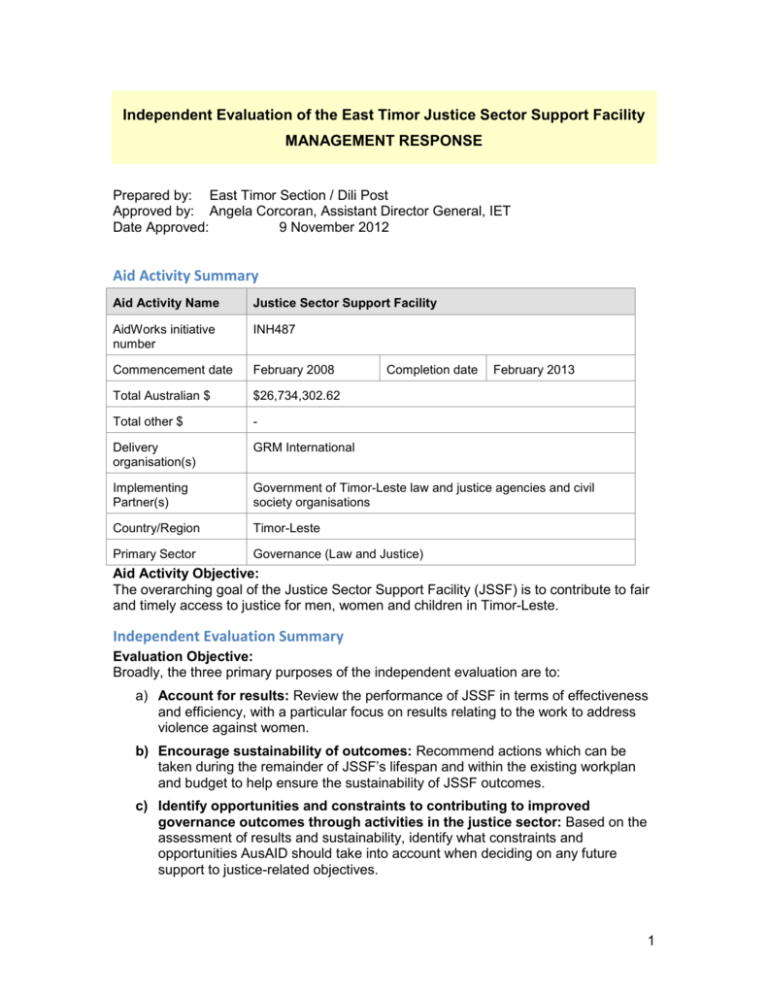

AusAID Timor-Leste Justice Sector Support Facility

advertisement