Type:Fish

advertisement

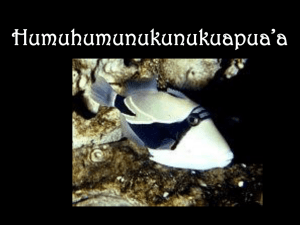

Parrot Fish Scaridae The beautifully colored parrot fish is known to change its shape, color, and even gender during its life. Map Parrot Fish Range Fast Facts Type: Fish Diet: Omnivore Average life span in the wild: Up to 7 years Size: 1 to 4 ft (30 to 120 cm) Group name: School Did you know? Some male parrot fish maintain harems of females. If the dominant male dies, one of the females will change gender and color and become the dominant male. Size relative to a tea cup: It's hard to decide which of the colorful parrot fish's many unique characteristics is most remarkable. There’s its diet, which consists primarily of algae extracted from chunks of coral ripped from a reef. The coral is pulverized with grinding teeth in the fishes’ throats in order to get to the algae-filled polyps inside. Much of the sand in the parrot fish's range is actually the ground-up, undigested coral they excrete. There's its gender, which they can change repeatedly throughout their lives, and their coloration and patterns, which are a classification nightmare, varying greatly, even among the males, females, and juveniles of the same species. Finally, there are the pajamas. Every night, certain species of parrot fish envelope themselves in a transparent cocoon made of mucous secreted from an organ on their head. Scientists think the cocoon masks their scent, making them harder for nocturnal predators, like moray eels, to find. Close relatives of the wrasse, parrot fish are abundant in and around the tropical reefs of all the world’s oceans. There are about 80 identified species, ranging in size from less than 1 to 4 feet (30 to 120 centimeters) in length. Their meat is rarely consumed in the United States, but is a delicacy in many other parts of the world. In Polynesia, it is served raw and was once considered "royal food," only eaten by the king Clown Anemonefish Amphiprion percula Safely living among the anemones, a clownfish swims in the warm waters off Papua New Guinea. Photograph by Wolcott Henry Clown Anemone fish Range Fast Facts Type:Fish Diet: Carnivore Average life span in the wild: 6 to 10 years Size: 4.3 in (11 cm) Group name: School Did you know? Ironically, Finding Nemo, a movie about the anguish of a captured clownfish, caused home-aquarium demand for them to triple. Size relative to a tea cup: Anyone with kids and a DVD player probably thinks they know all there is to know about the clown anemonefish, or, simply, clownfish. What they may not know is that the heroes of Finding Nemo are actually called false anemonefish. True anemonefish, Amphiprion percula, are nearly identical, but have subtle differences in shape and live in different habitats. Bright orange with three distinctive white bars, clown anemonefish are among the most recognizable of all reefdwellers. They reach about 4.3 inches (11 centimeters) in length, and are named for the multicolored sea anemone in which they make their homes. Clownfish perform an elaborate dance with an anemone before taking up residence, gently touching its tentacles with different parts of their bodies until they are acclimated to their host. A layer of mucus on the clownfish's skin makes it immune to the fish-eating anemone's lethal sting. In exchange for safety from predators and food scraps, the clownfish drives off intruders and preens its host, removing parasites. There are 28 known species of anemonefish, most of which live in the shallow waters of the Indian Ocean, the Red Sea, and the western Pacific. They are not found in the Caribbean, Mediterranean, or Atlantic Ocean. Surprisingly, all clownfish are born male. They have the ability to switch their sex, but will do so only to become the dominant female of a group. The change is irreversible. Nassau Grouper Description of Epinephelus striatus Description and Distribution The Nassau Grouper is buff-coloured, with five dark brown vertical bars and a large black saddle blotch on top of the caudal peduncle, and a row of black dots below and behind the eye. It has a distinctive dark tuning-fork mark beginning at the front of the upper jaw, extending dorsally along the interobital and bifurcating on top of the head behind the eyes. It has another dark band from the tip of the snout through the eye and then curves upward to meet its fellow just before the dorsal-fin origin. Some fish have irregular pale spots and blotches all over the head and body. The colour pattern can change in a few minutes from almost white to uniformly dark brown depending on the ‘mood' of the fish (1). The species is found in the western North Atlantic: Bermuda, Florida, Bahamas, Yucatan Peninsula and throughout the Caribbean (see above map - distribution indicated by dotted line). It is not known from the Gulf of Mexico, except at the Campeche Bank off the coast of Yucatan, at Tortugas and off Key West (1). Preferred Habitat This grouper is common on offshore rocky bottoms and coral reefs throughout the Caribbean region. It occurs at a depth range extending to at least 90 m, preferring to rest near or close to the bottom. Juveniles are found closer to shore in seagrass beds and macroalgal areas that offer a suitable nursery habitat. Nassau groupers are typically solitary and diurnal. However, they may occasionally form schools. When threatened by predators, this fish can camouflage itself, blending in with the surrounding rocks and corals (2). Biology Juveniles feed mostly on crustaceans and prefer seagrass and coral clumps with macroalgae (Laurencia spp.). Adults feed mainly fishes and crabs, and to a lesser extend on other crustaceans and molluscs. Growing to a maximum of 4 feet ( 1.2 m) and weighing over 50 pounds ( 22.7 kg), this grouper is one of the largest fish on the reef. More commonly, this grouper reaches a length of 1-2 feet (0.3 -0.6 m) and weighs 10-20 pounds (4.5 -9 kg). The species lives at least 16 years and possibly as much as 29 years (3)(10). Sexual maturation takes place at about 5 years and at about 400 -450 mm SL in both males and females (about 500 mm TL). The species is not known to change sex (unlike many other grouper which exhibit female to male sex change) based on histological, age and size evidence, but this might be related to fishing pressure. Among fish sampled in one study, there was not evidence for functional hermaphroditism with males and females overlapping in size and age and gonochorism indicated. However, it is possible that fishing pressure has eliminated most of the larger males and that the species is naturally diandric. The largest males in this case would be secondary (derive from sex changed females) and the smaller males derived directly from juveniles. It may be just these smaller males that remain and join the spawning aggregations (4). Spawning aggregations of a few dozen to perhaps as many as 100,000 individuals have been reported from the Bahamas, Jamaica, Cayman Islands, Belize, the Virgin Islands and elsewhere in the Caribbean within the greymarked area of the above map. Aggregations are not known to form elsewhere within the geographic range of the species. Many of the islands or banks in the Caribbean have, or had in the past, spawning aggregations, unfortunately many appear to have been fished to commercial "extinction" (3). See aggregation photo above. These aggregations occur in depths of 20 to 40 m at specific locations of the outer reef shelf edge in December, January and/or February at or near the time of the full moon; the same sites are used year after year. During spawning, most fish (males and females) display the bicoloured (non-aggressive) pattern and hover above the bottom. See photo of bicolor female distended with eggs, above. Some females remain in the barred pattern, becoming very dark as mating approaches and are closely followed by bicoloured fish during courtship (3). Spawning occurs at sunset, in groups of 3 to 25 fish. Release of gametes is preceded by various movements of the courting groups: vertical spirals, short vertical runs followed by rapidly crowding together then rapidly dispersing and horizontal runs near the bottom. Mating is initiated by a dark phase fish (presumed female) dashing forward and upward, the female is closely followed by groups of bicoloured males releasing a white cloud of sperm as the female(s) release her eggs (5). Queen Angelfish Holacanthus ciliaris The queen angelfish gets its name from the crown-like ring on its head. Its diet consists mostly of sponges and algae. Photograph courtesy Chris Huss/NOAA Map: Queen Angelfish Range Fast Facts Type:Fish Diet:Omnivore Average life span in the wild:Up to 15 years Size:Up to 18 in (45 cm) Size relative to a 6-ft man: Weight:Up to 3.5 lbs (1.6 kg) Group name:School Did you know? Young queen angelfish feed by setting up cleaning stations in sea grass where larger fish come to have their skin parasites removed. Queen angelfish get their royal title from the speckled, blue-ringed black spot on their heads that resembles a crown. Decked out with electric blue bodies, blazing yellow tails, and light purple and orange highlights, Queen angels are among the most strikingly colorful of all reef fishes. Their adornments seem shockingly conspicuous, but they blend well when hiding amid the exotic reef colors. They are shy fish, found either alone or often in pairs in the warm waters of the Caribbean and western Atlantic. Fairly large for reef-dwellers, they can grow up to 18 inches (45 centimeters) in length. They have rounded heads and small beak-like mouths, and, like other angelfish, their long upper and lower fins stream dramatically behind them. Their diet consists almost entirely of sponges and algae, but they will also nibble on sea fans, soft corals, and even jellyfish. Queen angels are close relatives of the equally striking blue angelfish. In fact, these two species are known to mate, forming natural hybrids, a very rare occurrence among angelfish. They are widely harvested for the aquarium trade, but are common throughout their range and have no special protections or status. Trumpetfish, Aulostomus maculatus [edit] Description & Behavior Named for its long, thin snout and body to match, trumpetfishes, Aulostomus maculatus (Valenciennes, 1837), aka Atlantic trumpetfishes, are a relative of seahorses. Masters of camouflage, trumpetfishes are usually mottled reddish brown—though some individuals may be yellow or green, with blue or purple heads—and can easily change color. They often swims vertically with their snouts down, which helps them to blend in with surrounding sea fans, pipe sponges and sea whips, thereby hiding from predators. Trumpetfishes may exceed a meter in length, with the head representing about one third of that length. Their chins have a small barbel. Two closely-related species, also called trumpetfish, are the Atlantic cornetfish, Aulostomus strigosus, which is found in the eastern Atlantic around Cape Verde (including other islands) and along the tropical West African coast, and the Chinese trumpetfish, Aulostomus chinensis, which lives in the waters of the Indo-Pacific, from east Africa to Hawaii and Easter Island, north to southern Japan and south to Lord Howe Island and in the eastern central Pacific from Panama, Revillagigedo Islands, Clipperton Island, and Cocos Island to Malpelo Island. World Range & Habitat Trumpetfishes, Aulostomus maculatus, usually live near grassy or weedy areas or coral reefs at depths from 2 to 25 m. In the Western Atlantic, they can be found in the tropics from southern Florida to northern South America and are also seen in Bermuda, the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean. Feeding Behavior (Ecology) Trumpetfishes are voracious and have crafty means of catching their food. They are known to use large herbivorous fish as camouflage, essentially shadowing them until they find the right moment to strike. If it's smaller fish or shrimp the trumpetfish is interested in, it will hang vertically in the water column, drifting with the current, as when hiding from its own predators—then ambush any prey unlucky enough to swim beneath it, sucking it up using a method called "pipette feeding." The trumpetfish's mouth creates the vacuum needed to suck up small animals by expanding to a size equal to the diameter of the body. Even animals larger than the trumpetfish's mouth are not safe—the elastic tissues can stretch to accommodate quite a sizable meal. Life History Like many fish, trumpetfishes have an elaborate courtship ritual or "dance." Their color-changing abilities, so often used for camouflage, are also employed here. As in their relatives, the seahorses, trumpetfishes place much of their reproductive burden on the males. After the dance, the female trumpetfish transfers her eggs to the male, who fertilizes and carries them in a pouch until they are born. Conservation Status Trumpetfishes are harmless to humans. They are not yet endangered and are increasingly popular in home aquariums, though they may be difficult to properly feed. Flying Fish Exocoetidae A streamlined torpedo shape helps flying fish generate enough speed to break the water’s surface, and large, wing-like pectoral fins help get them airborne. Photograph by Peter Parks/Animals Animals-Earth Scenes Map: Flying Fish Range Fast Facts Type:Fish Diet:Omnivore Size:Up to 18 in (45 cm) Group name:School Size relative to a tea cup: Did you know? Flying fish can soar high enough that sailors often find them on the decks of their ships. Flying fish can be seen jumping out of warm ocean waters worldwide. Their streamlined torpedo shape helps them gather enough underwater speed to break the surface, and their large, wing-like pectoral fins get them airborne. Flying fish are thought to have evolved this remarkable gliding ability to escape predators, of which they have many. Their pursuers include mackerel, tuna, swordfish, marlin, and other larger fish. For their sustenance, flying fish feed on a variety of foods, including plankton. There are about 40 known species of flying fish. Beyond their useful pectoral fins, all have unevenly forked tails, with the lower lobe longer than the upper lobe. Many species have enlarged pelvic fins as well and are known as four-winged flying fish. The process of taking flight, or gliding, begins by gaining great velocity underwater, about 37 miles (60 kilometers) per hour. Angling upward, the four-winged flying fish breaks the surface and begins to taxi by rapidly beating its tail while it is still beneath the surface. It then takes to the air, sometimes reaching heights over 4 feet (1.2 meters) and gliding long distances, up to 655 feet (200 meters). Once it nears the surface again, it can flap its tail and taxi without fully returning to the water. Capable of continuing its flight in such a manner, flying fish have been recorded stretching out their flights with consecutive glides spanning distances up to 1,312 feet (400 meters). Flying fish are attracted to light, like a number of sea creatures, and fishermen take advantage of this with substantial results. Canoes, filled with enough water to sustain fish, but not enough to allow them to propel themselves out, are affixed with a luring light at night to capture flying fish by the dozens. There is currently no protection status on these animals. Take one look at a great barracuda's toothy grin and you'll understand why it has earned the nickname "Tiger of the Sea." With its sleek, torpedo-like body, dagger-like teeth, and ferocious appetite, the barracuda is built to hunt in the ocean. And that's exactly what it has been doing for the last 50 million years. Any diver who's seen a barracuda attack another fish can tell you that it happens faster than you can say "anchovy." One moment, a barracuda will be drifting lazily among the coral reefs. The next, it's rocketing toward a fish and snapping it up in its jaws. The Great Eating Machine The great barracuda is an eating machine and it has the bulk to prove it. While some species of barracuda are less than a foot long, the great barracuda can measure up to 6 feet and weigh as much as 100 pounds. That's one big hungry fish! So, is the barracuda a cold-blooded killer? You betcha! A barracuda is a predator because it needs to eat to survive. And it's cold-blooded because all fish are cold-blooded. They adapt to the temperature of the water surrounding them. Barracudas Are Fishy! If you think a barracuda is fishy looking, you're right. It's a fish. A barracuda shares several traits with most other fish, in addition to being cold-blooded. It is a vertebrate — it has a spine. It has scales covering its body. It breathes using its gills rather than its lungs. It lays eggs rather than giving birth to live young. And, it swims by moving its fins (including its tail). In order to move up and down quickly to track its prey and to move around the coral reefs, the barracuda uses itsswim bladder. A swim bladder is what keeps a fish from sinking to the bottom of the ocean, even though it's heavier than seawater. A barracuda can inflate or deflate this gas-filled chamber to lower its body or to rise. Yes and no. Yes, they need to Do Fish Breathe breathe oxygen to survive. But, Like Us? Barracuda are better adapted to hunting in the coral no, they don't breathe the reefs than, say, a tuna because their bodies, same way we do. Fish don't though long, are flexible enough to move through the have lungs at all. They have twists and turns of a reef. accordian-like organs called gills. In order to breathe, most If it's such a great hunter, does this make the fish gulp water in through their barracuda the most successful animal in the ocean? mouths and pump it over their That's hard to measure. It hasn't been around for 50 gills. So when you see a million years just because it's lucky. But fish in general barracuda opening wide, it's are an extremely successful class of animals. There are probably just getting a breath more than 25,000 different species of fish. This makes of "fresh air." them, by far, the largest group of vertebrates. And there are millions, if not billions, of them. The oldest kinds of fish swam the seas more than 400 million years before the first dinosaur roamed the earth. So the next time you see a fish, show it a little respect, especially if it's a 'cuda Triggerfish Balistidae Triggerfish are infamous for their nasty attitude and this behavior is especially evident around nests, where intruders, from other fish to human divers, are likely to be charged or bitten. Photograph by Georgie Holland, Photolibrary Fast Facts Size relative to a 6-ft (2-m) man: Type:Fish Diet:Carnivore (most species) Size:Up to 3.3 ft (1 m) Group name:Harem Protection status:Varies by species Did you know? A triggerfish can rotate each of its eyeballs independently. The 40 species of triggerfish are scattered throughout the world’s seas and are familiar to divers and aquarium aficionados. Largest of all is the stone triggerfish, which reaches up to 3.3 feet (1 meter) long, found in the Eastern Pacific from Mexico to Chile. These bottom dwellers dig out prey, such as crabs and worms, by flapping away debris with their fins and sandblasting with water squirted from their mouths. They also use very tough teeth and jaws to take on sea urchins, flipping them over to get at their bellies, which are armed with fewer spines. Triggerfish wreak such havoc on less fortunate reef dwellers that smaller fish often follow them to feast on their leftovers. The Balistidae family takes its common name from a set of spines the fish use to deter predators or to “lock” themselves into holes, crevices, and other hiding spots. The system can be "unlocked" by depressing a smaller, “trigger” spine. Triggerfish tend to be solitary but meet at traditional mating grounds according to timetables governed by moons and tides. The males of many species appear to establish territories on these spawning grounds and prepare seafloor nests that will house tens of thousands of eggs. Females share care of the eggs until they hatch, blowing water on them to keep them well supplied with oxygen. In some species males are known to maintain a harem of female mates. Triggerfish are infamous for their nasty attitude and this behavior is especially evident around nests, where intruders, from other fish to human divers, are likely to be charged or bitten. Triggerfish are attractive animals and some species have become too popular for their own good. They are sought for the aquarium trade, which has prompted fishermen to gather even threatened species from the wild. Researchers are working to raise triggerfish in captivity so that wild populations might more likely be left alone. Black Sea Bass Black Sea Bass Once deemed overfished, the North Atlantic population is now rebuilding and has been recently promoted from an overfished status. Consumer Note The terms “bass,” “sea bass” and “seabass” are commonly applied to a range of different fish species besides black sea bass, including toothfish, croaker and rockfish. Summary Black sea bass, a true sea bass, is commonly caught by commercial and recreational fishermen, along the entire U.S. Atlantic coast. The most common methods used to fish for black sea bass in the north Atlantic are trawling, pots and traps and hook-and-line. There are some environmental concerns associated with trawling and pots and traps, such as habitat destruction and bycatch, especially with trawling. The South Atlantic (south of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina) population is severely overfished. Trawling was banned in this fishery in 1998, reducing the amount of bycatch and habitat damage. Because of overfishing, we recommend consumers "Avoid" black sea bass caught in the South Atlantic. Physical description: The larger individuals of black sea bass are black, while the smaller induviduals are more of a dusky brown. The exposed parts of scales are paler than the margins, giving the fish the appearance of being barred with a series of longitudinal dots. The belly is only slightly lighter in color than the sides. The fins are dark, and the dorsal is marked with a series of white spots and bands. The upper portion of the caudal fin ends as a filament. During spawning, males may have a conspicuous blue nuchal hump. Biological description: The black sea bass is a temperate marine species that inhabits irregular hard-bottom areas, such as wrecks or reefs. They are found from Cape Cod to Cape Canaveral, and those found in the South Atlantic Bight usually occur more inshore with other tropical reef fish such as snappers, groupers, porgies and grunts. Black sea bass are protogynous hermaphrodites, that is, they change sex with size. Large individuals are males, and smaller individuals are female. The number of eggs produced in a spawning season ranges from 30 thousand to 500 thousand depending on the size of the fish. The spawning season is June through October in the Mid-Atlantic Bight, and February through May in the South Atlantic Bight. Females reach sexual maturity when they are 7.5 inches long, and males when they are 9 inches long. Black sea bass may live up to 20 years, although fish older than 9 years are rare. The maximum size attained is 24 inches and 6 pounds. Black sea bass are opportunistic feeders eating whatever is available, preferring crabs, shrimp, worms, small fish and clams. Butterflyfish Chaetodontidae Butterflyfish are a common site near coral reefs, which they peck with their protruding snouts searching for polyps, worms, and other small invertebrates. Photograph by Tim Laman Map: Butterfly Fish Range Fast Facts Type:Fish Diet:Omnivore Size:8 in (20 cm) Group name:School Did you know? At night, butterfly fish settle into dark crevices, and their brilliant colors and markings fade to blend with the reef background. Size relative to a tea cup: Butterflyfish, with their amazing array of colors and patterns, are among the most common sites on reefs throughout the world. Although some species are dull-colored, most wear intricate patterns with striking backgrounds of blue, red, orange, or yellow. Many have dark bands across their eyes and round, eye-like dots on their flanks to confuse predators as to which end to strike and in which direction they're likely to flee. There are about 114 species of butterflyfish. They have thin, disk-shaped bodies that closely resemble their equally recognizable cousins, the angelfish. They spend their days tirelessly pecking at coral and rock formations with their long, thin snouts in search of coral polyps, worms, and other small invertebrates. Some butterflyfish species travel in small schools, although many are solitary until they find a partner, with whom they may mate for life. Their presence or absence may be used to gauge the general health of a reef since many rely upon live coral as food, while others feed upon invertebrates, algae, or zooplankton. Butterflyfishes may be solitary, form aggregations, or pairbond with a mate. Bold color patterns provide visual cues to other fish and provide some protection from predators. There are 25 species of Butterflyfishes in Hawai‘i, 123 throughout the world, of which four are endemic. The Hawaiians referred to these as lauhau, lauwiliwili, or kīkākapu and did not eat them except during famine. Damselfish Damselfish belong to the Pomacentridae family. Most available fish belong to one of the following genera: Abudefduf, Dascyllus, Chromis, Chrysiptera, Paraglyphidon, Pomacentrus, and Stegastes. Damselfish are closely related to Clownfish, which are also a member of the Pomacentridae family. Damselfish are found throughout the world, and are almost always associated with coral reefs. The average size of most Damsels in an aquarium is around two inches, but in the wild the largest member of this family reaches over 14 inches in length. Damselfish are often used to break in or cycle a new aquarium. It is important to remember that even though these fish are hardy and can handle the adverse conditions of a new aquarium, they may become quite aggressive among themselves, and toward other tankmates. Most of these fish stay in small shoals in the wild when young, breaking away from the group as they grow, and eventually become solitary as adults. When dealing with several Damsels in one aquarium, plenty of rockwork and hiding places are necessary in order to keep quarrels to a minimum. The Chromis are a genus of Damsels that are schooling fish. They do well in an aquarium in groups of the same species. No significant markings or distinguishing characteristics differentiate males from females. Damselfish can be successfully spawned in an aquarium. The male Damsel is usually responsible for the care and maintenance of the eggs after the fish have spawned. Allen's Damselfish Black and White Chromis Black Damselfish Blackmouth Chromis Blacktail Damselfish Blue and Gold Damselfish Blue Damsel/Blue Devil Blue Green Chromis Blue Reef Chromis Fiji Blue Devil Damselfish Golden Damselfish Half-blue Damselfish Honey Head Damselfish Javanese Damselfish Jewel Damselfish Reticulated Damselfish Sergeant Major Damselfish Smith's Damselfish Talbot's Damselfish Three Spot Damselfish Three Striped Damselfish Yellowtail Blue Damsel Damselfish (family Pomacentridae) create bright ovals of energetic color on the reefs. They are very common and so plentiful that the reef seems to be alive with darting, turning, hiding, often curious small colorful ovals. There are over 240 species of damselfish in the Indo-Pacific. They all have a continuous dorsal fin and a forked or lunate tail. They are all egg layers. Either the male or female makes a nest on the bottom where they engage in courtship displays of rapid swimming and fin extension. They feed on algae or plankton. Included in this family are damselfish, sergeants, chromis, Dascyllus, and demoiselles. Photos copyrighted Hackingfamily.com, with credits to Christopher Hacking unless otherwise noted. Brightly colored Anemonefish (yes, related to Nemo, the clownfish!) live co-existent lives with about 10 species of host anemone. While it seems clear that the anemone, with its stinging tentacles, offers protection to the fish, it is not so clear what the fish offers the anemone. Perhaps nothing, as anemones without fish are commonly seen, but the anemonefish are never seen far away from the protection of an anemone. Anemonefishes live in small groups with a dominant female and a smaller, sexually active male, and several even smaller males and juveniles. When the dominant female dies, the largest male changes sex to become the head of the harem. We believe this species in the photo is Amphiprion bicentrus, in Tahitian Atoti. It baffled us for a long time because it's not in any of our ID books. We finally saw a picture in a museum in Tahiti which showed the Atoti with its all-orange body with two white/blue bars, the rear one thinner. (Moorea) Pink Anemonefish Amphiprion perideraion looks hauntingly pitchfork-esque from the front, and appears more orange than pink amongst the purple-tipped Magnificent Anemone. The Pink Anemonefish lives in 4 different anemones but prefers the Magnificent. It's found from Indonesia across to E. Micronesia, and from Japan south to the Great Barrier Reef. (New Caledonia) The adult Red And Black Anemonefish Amphiprion melanopus (left) is found from Indonesia across the Pacific to French Polynesia. Strangely, the adults in Tonga and Fiji vary from other adults by having no black on the back. The young (right) have 2 to 3 white (or pale blue/white) bars. They live with any of 3 different anemone species to 30' (10m) deep. (Adult: New Caledonia. Juvenile: Tonga) The more subtly colored Staghorn Damsels Amblyglyphidodon curacao live near Acropora coral on shallow reefs in the western Pacific from Vanuatu, Fiji and Samoa north to Japan and south to the Great Barrier Reef of Australia. They may be found as deep as 15 meters. (Fiji) The lovely Blue Damsel Pomacentrus pavo is common on small coral heads in French Polynesia. Their distinguishing mark, aside from the yellowish tail, is a dark "ear" spot, just visible in this shot. (Society Islands, Fr. Polynesia) We saw this lovely little white and yellow, black-finned Damsel on a dive in the Vava'u Group of Tonga in September. We have not been able to identify it. Any help? (Tonga) The Black Damsel Neoglyphidodon melas juvenile is stark and colorful, belying its name. We have no good photo of the adult, a fact which I shall blame on its featurelessness. To picture it, envision a damsel-shaped black hole. Now compare that image with the photo, and you will understand how the juvenile was once considered to be a different species, until intermediates were found. The Black Damsel is usually solitary and found on soft-coral reefs. (Lizard Island, Australia) The juvenile Three-spot Dascyllus Dascyllus trimaculatus (black and white, left) are small damselfish that often hang out in anemones with Anemonefish (orange face and white bar). As the former mature (right) they lose their spots to become sort of drab gray/black fish about 5-6 inches (15 cm) long. If they're not fully mature, they may still have a spot or two, as in the picture on the right. The only distinguishing mark is the pale rear dorsal fin. Strange how nature gives the striking patterns to juveniles and leaves the adults alone. I would think a predator would find the juveniles more easily than the adults! (Society Islands, Fr. Polynesia) We think this is a Yellow-Tailed Dascyllus Dascyllus flavicaudus, due to the yellow tail, but the description in our guide talks of a medium brown to dark brown body. (The blue-yellow sheen could just be the camera flash.) The dark spot on the upper pectoral fin base is also characteristic. The blue lip? Well, we don't know. (Society Islands) With the unlikely name of Humbug Dascyllus Dascyllus aruanus, these bright splashes of black and white dart and swim around various coral heads seeking shelter and eating algae and plankton. The white spot across the eyes is characteristic, as is the black ventral fin. (Society Islands, French Polynesia) With its bright neon-blue stripe extending from snout to below the rear dorsal fin, the 3-and-a-half-inch (8 cm) Surge Demoiselle Chrysiptera brownriggii is hard to miss. It is found in surge channels and outer reef flats to about 35 feet or 12 meters. (Fr. Polynesia) The Yellowtail Demoiselle Neopomacentrus azysron almost seems to be a different type of fish from the Surge Demoiselle above, given its modest coloring. The black 'ear spot' above the pectoral fin is characteristic. Yellowtail Demoiselles form schools to 12m. (Australia) The tiny Blue-Green Chromis Chromis viridis (left and right) grow to only 3 inches (7cm), but are bright against the corals down to a depth of 65' (20 meters). They form large schools around thick coral gardens. They can be anywhere from blue to pale green, and have no distinctive markings except for a faint line from the eye forward to the upper lip. This characteristic is shared by the Black-Axil Chromis, which is distinguished by a black spot at the base of the pectoral fin. Photo right: Society Islands, French Polynesia. Photo left: Mamanucas, Fiji A very abundant fish on the reefs of Tonga was the unmistakable Pacific Half-and-Half Chromis Chromis iomelas with its black fore-body and white rear body. We saw them mostly on scuba dives in more than 15 feet (5 meters) of water. They grow to just under 3 inches (about 8 cm) and were found either in large groups or solitary, such as the one above that swims over a blooming leather coral. (Tonga) General and Feeding habits of Sergeant Major Damsel Fish Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Actinopterygii Order: Perciformes Family: Pomacentridae Genus: Abudefduf Species: A.saxatilis Binomial name: Abudefduf saxatilis The Sergeant Major Damsel Fish is a beautiful, hardy saltwater fish that can make a lovely addition to many aquariums. Larger than most Damsel Fish, Sergeant Majors have dramatic colorations. The Sergeant Major Damsel Fish was first referred to as Abudefduf saxatilis by Carl Linnaeus (1758). The scientific name abudefduf translates as “father”, saxa as “living among rocks”, and tilus as “tile-like in color”. It is called father due to its bossy, aggressive behavior towards other inhabitants on the reef. In the wild, Sergeant Major Damsel Fish live in the coral reefs of the Atlantic Ocean. They feed on plankton that they are able to find in the reefs or rocky areas where they live. They tend to be rather aggressive and may bully other inhabitants of the reef. For this reason, Sergeant Major Damsel Fish may not do well with smaller, peaceful fish or with conspecifics in a saltwater aquarium, though they are reef safe, if kept with compatible species. In the wild they live at depths between 1 and 12 meters. The Sergeant Major Damsel Fish feeds on a variety of food items including algae, small crustaceans, various invertebrate larvae, and fishes. Stomach content analysis reported benthic algae, pelagic algae, and plankton including copepods, shrimp larvae, fish, and pelagic tunicates as specific prey items of this fish. One of the larger Damsel Fish, Sergeant Major Damsel Fish often reach lengths of six or seven inches (15 to 18 centimeters), though some have been reported to reach eight inches (20 centimeters) in length. Their upper bodies are yellow, often with blue tints. They are laterally flattened. The lower body of the Sergeant Major Damsel Fish is whitish with some gray coloring. There are dark spots on the pectoral fins, one at the base of each fin. There are also five black vertical stripes, which run the height of the body and narrow toward the underside of the fish. The mouth of the Sergeant Major Damsel Fish is small, and the single dorsal fin has a continuous structure. Sergeant Major Damselfish are associated with shallow reefs This reef-associated fish is commonly observed forming large feeding aggregations of up to a few hundred individuals. These schools swim over shallow reef tops at depths of 3-50 feet (1-15 m). Spawning among Sergeant Major Damselfish mates occurs on rocks, shipwrecks, pilings, and reef outcroppings where the male sergeant major prepares the nest. Courtship rituals include males actively chasing the female during the morning hours. During this time, the males build nests. During spawning, approximately 200,000 eggs are released. These eggs are salmon or red colored, oval-shaped, and 0.5-0.9 mm in diameter. Upon fertilization, the eggs turn greenish at 96 hours and contain a deep red yolk. An adhesive filament attaches the egg to the bottom substrate. The male Sergeant Major takes on a bluish color while guarding the fertilized eggs. He guards them until they hatch which occurs within 155-160 hours following fertilization. This guarding of the eggs, characteristic of the family Pomacentridae, is unusual since most reef fishes have a planktonic stage. The larvae reach 2.4 mm in length approximately 36 hours after hatching. They are deep-bodied, with the caudal and pectoral fins visible, prominent lips, and well-developed jaw bones. Sergeant Major Damsel Fish get their names from the five black stripes over there bodies that resemble those of a Sergeant Major’s insignia. They inhabit warm reef shallows in the Atlantic Ocean. Sergeant Major Damsel Fish, when kept individually, should have an aquarium of at least 20 gallons in size. They are reef safe. Because of their aggressive natures, Sergeant Major Damsel Fish should only be kept with other large fish with similar temperaments. Sergeant Major Damsel Fish can be maintained quite nicely on flake food, and are often offered brine shrimp, algae, and frozen foods. Sergeant Major Damsel Fish mate between the months of April and August. Males turn deep blue in color and often become quite territorial. The range of the Sergeant Major Damsel Fish is worldwide in warm waters. In the Atlantic Ocean, this fish occurs from Rhode Island (U.S.) to Uruguay. It is quite abundant on Caribbean Sea reefs as well as around islands in the mid-Atlantic region. In the eastern Atlantic Ocean, its range includes Cape Verde, along the tropical coast of western Africa, south to Angola. Some common names for this fish are Sergeant Major, Damsel fish, Five finger, and Pilotfish. This fish gets its common name “sergeant major” from the stripes that resemble the traditional insignia of the military rank.