extended

advertisement

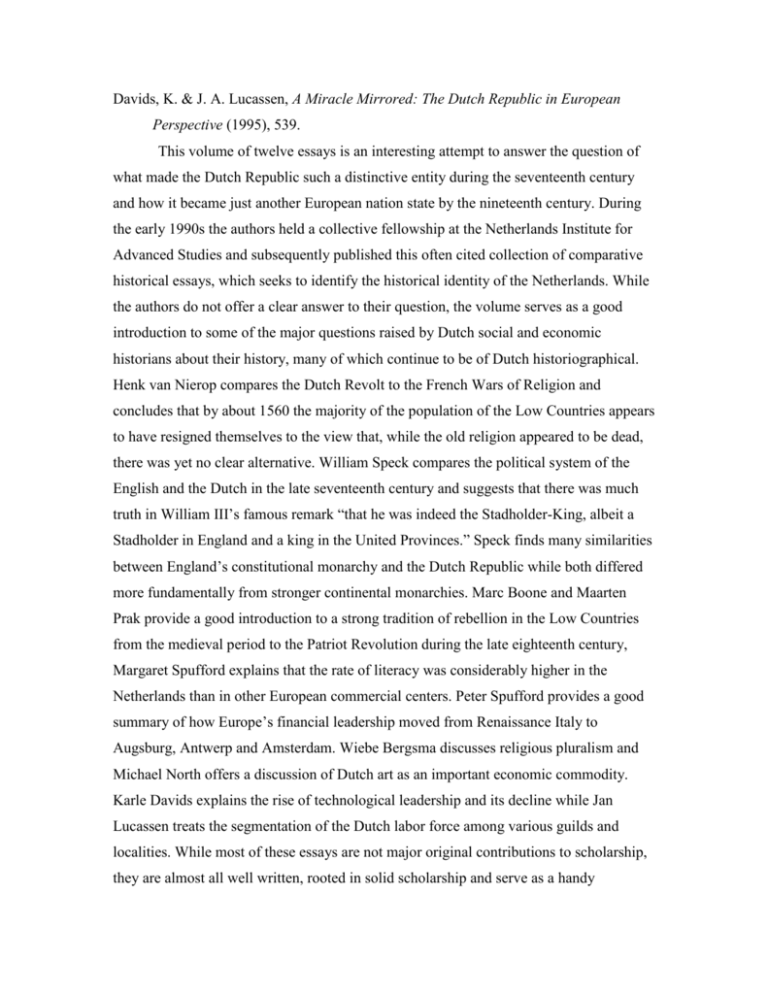

Davids, K. & J. A. Lucassen, A Miracle Mirrored: The Dutch Republic in European Perspective (1995), 539. This volume of twelve essays is an interesting attempt to answer the question of what made the Dutch Republic such a distinctive entity during the seventeenth century and how it became just another European nation state by the nineteenth century. During the early 1990s the authors held a collective fellowship at the Netherlands Institute for Advanced Studies and subsequently published this often cited collection of comparative historical essays, which seeks to identify the historical identity of the Netherlands. While the authors do not offer a clear answer to their question, the volume serves as a good introduction to some of the major questions raised by Dutch social and economic historians about their history, many of which continue to be of Dutch historiographical. Henk van Nierop compares the Dutch Revolt to the French Wars of Religion and concludes that by about 1560 the majority of the population of the Low Countries appears to have resigned themselves to the view that, while the old religion appeared to be dead, there was yet no clear alternative. William Speck compares the political system of the English and the Dutch in the late seventeenth century and suggests that there was much truth in William III’s famous remark “that he was indeed the Stadholder-King, albeit a Stadholder in England and a king in the United Provinces.” Speck finds many similarities between England’s constitutional monarchy and the Dutch Republic while both differed more fundamentally from stronger continental monarchies. Marc Boone and Maarten Prak provide a good introduction to a strong tradition of rebellion in the Low Countries from the medieval period to the Patriot Revolution during the late eighteenth century, Margaret Spufford explains that the rate of literacy was considerably higher in the Netherlands than in other European commercial centers. Peter Spufford provides a good summary of how Europe’s financial leadership moved from Renaissance Italy to Augsburg, Antwerp and Amsterdam. Wiebe Bergsma discusses religious pluralism and Michael North offers a discussion of Dutch art as an important economic commodity. Karle Davids explains the rise of technological leadership and its decline while Jan Lucassen treats the segmentation of the Dutch labor force among various guilds and localities. While most of these essays are not major original contributions to scholarship, they are almost all well written, rooted in solid scholarship and serve as a handy introduction to major topics in Dutch social and economic history. The essay by Luiten van Zanden and Leo Noordegraaf does break new ground and is a good introduction to an important on-going research program that seeks to explain in a worldwide comparative perspective on why Dutch workers enjoyed the highest standard of living in the world during the early modern period. Van Zanden has done a great deal of work on this subject since this essay was published and perhaps the wealth of the Republic’s workers and middle classes has become its most lasting legacy.