Click here to read the sermon - Somerset Congregational Church

advertisement

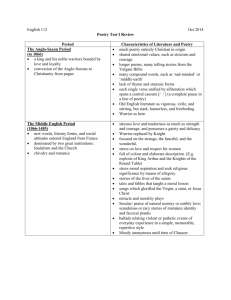

Old Testament Poetry February 1, 2015 Psalm 103 We are in the middle of a sermon series entitled: How to Read the Bible for All It’s Worth. And what we are doing is examining the different literary genres of the Bible and how we ought to read them and interpret them in the hopes of better equipping each of you to read your Bibles with more confidence and excitement. To that end, I have been encouraging you to follow along with the sermon insert filling in the blanks so that each week you can use it to help you read the suggested readings found on the back of the insert. Our genre today is Old Testament Poetry. And before we dive in, here are some fun poetry jokes. Intro Jokes: Question: Why did the traffic cop give the poet a ticket? Answer: For driving without a poetic license. Question: Why are poets always so poor? Answer: Because rhyme doesn’t pay. Question: Why do poets despise writing commercial jingles? Answer: Because jingles are ad-verse. Question: Why did the boy poet introduce himself to the girl poet? Answer: Because he wanted to meter. Here’s a poem for you: I dig, you dig, we dig, he digs, she digs, they dig. It's not a beautiful poem, but it's very deep. Let’s jump right in. Poetry is a big genre in the Bible especially in the Old Testament where it accounts for 1/3 of the whole Old Testament. In fact, these past two weeks if you read the suggested readings in the Prophets, you were primarily reading poetry. The Prophets were big time poets, that’s how God wanted them to communicate, through poetry and we’ll get to why that was later on. Of course almost all the books of the Old Testament include poetry, but the one we’ll most focus on primarily today is the Psalms, which is all poetry. But before we turn to the Psalms, let’s ask this question first: What is Old Testament Poetry and how does it differ from other genres, especially prose? What is Old Testament Poetry? I heard that a good definition of poetry in general is “a painting in words”. And much like modern poetry, ancient poetry has a distinct style and rhythm that is used to express feelings and ideas in a way that straight prose or scientific descriptions cannot. Let’s look at three features that set apart Old Testament Poetry. 1. First, Hebrew poetry, like today has a meter or rhythm to it. It’s easy for us to understand rhythm in nursery rhymes like: Hickory, dickory, dock; the mouse ran up the clock; the clock struck one; the mouse ran down; hickory, dickory dock. There is a flow to that rhyme, based on the syllables in each line. Now, that is not going to be much help to us concerning ancient Hebrew poetry, because we are reading an English translation and so we are going to lose out on the meter. But it’s there and it is one of the things that helps translators figure out if what they are reading is indeed poetry. 2. Secondly, Old Testament Poetry used a device called parallelism where two lines of poetry are used together to communicate one idea. Now, unlike meter, parallelism is still very evident to us using our English translations. Hebrew Poetry is usually broken up into relatively short lines. Typically you would have one line state a thought and a second line parallel to it that would restate the thought in a slightly different way. Please turn in your Bibles to Psalm 25 on page 863 and we’ll take a look at the three most typical types of parallelism, all found in Psalm 25. Let’s read the first two verses, “To you, O LORD, I lift up my soul; 2 in you I trust, O my God. Do not let me be put to shame, nor let my enemies triumph over me.” Here we have two examples of synonymous parallelism where the second line restates the first line using different words. Line 1 is: To you, O LORD, I lift up my soul; Line 2: in you I trust, O my God. And then a new line 1: Do not let me be put to shame, Line 2: nor let my enemies triumph over me. Do you see how the second line is simply repeating the first line, but it gives you another angle to think about it, it gives deeper meaning to the idea the poet is trying to share. And by and large, synonymous parallelism is the most frequent parallelism you’ll find in Hebrew poetry. But, let me share with you two other frequent types: the next would be antithetical parallelism, which as the name implies is where the second line contrasts with the first line. And verse 3 of Psalm 25 is a great example of this: Line 1: “No one whose hope is in you will ever be put to shame;” Now watch the contrast here in line 2: “but they will be put to shame who are treacherous without excuse.” The word “but” is a dead giveaway that the second line is contrasting the first and thus using antithetical parallelism. One last type major type is called synthetic parallelism in which the second line develops or completes the thought of the first. So it doesn’t contrast it nor does it simply repeat it, but the second line develops the first. Verses 8 & 10 are good examples of this. Line 1 of v. 8 “Good and upright is the LORD;” Line 2 “therefore he instructs sinners in his ways.” Line 2 didn’t repeat or contrast, instead it completed, it developed the first line. Verse 10 does the same, Line 1: “All the ways of the LORD are loving and faithful” Line 2: “for those who keep the demands of his covenant.” By the way, before we move on, it is good to note that your modern Bibles have done a lot of the work for you already when it comes to poetry. Did you notice how Psalm 25 appears on the page? How it uses indentations to guide you in figuring out where one line starts and the next line of poetry begins? Now, I don’t expect you to leave here today remembering the specifics about parallelism, but it’s a major part of what makes up Biblical poetry, so I hope it’s at least on your radar now when you read it. 3. Let’s look at one last feature of ancient poetry, which is still a feature of modern poetry: figurative language. That is it uses lots of metaphors and similes, which if you can go back to high school, you’ll remember that both metaphors and similes describes something in a non-literal way. The big difference between them is that a simile uses the word “like” or “as” and a metaphor does not. What this means is that when you read poetry in the Bible, you need to be looking for the intent of the figurative language. What does the author want me to know through the figurative language? For example, let’s look at the 23rd Psalm, which begins, “The LORD is my shepherd, I shall not be in want. He makes me lie down in green pastures, he leads me beside quiet waters,” If we take it literally, we would come to believe that God is an actual shepherd and he wants us to act like sheep or perhaps he wants us to live a rural life in the country. But of course we realize that this is a metaphor and what the author intends for us to realize through the poetry is that our God cares for us, He protects us, He provides for us. I think this should help us to answer the question you sometimes hear, which is this “should we take the Bible literally?” Do you take the Bible literally?” The answer to that is yes and no. Yes, I take literally the parts of the Bible that are meant to be taken literally, like the Historical accounts of Abraham, Moses, the nation of Israel, the accounts of Jesus and the disciples. I take all of those literally because they were written to be taken literally, but I don’t take the psalms and other poetry in the Bible literally, because they use figurative language & are in most cases not meant to be taken in such a literal fashion. Now, then again, if someone asks you if you take the Bible literally, they might just be asking if you take it seriously or do you think it’s just a bunch of stuff made-up or at least irrelevant to our lives today. And to that, we must answer with an emphatic yes and perhaps a quick explanation of what you mean by that. Yes, I take the whole Bible seriously, but I only take literally the parts of the Bible that were intended to be taken literally. Types of Poetry Ok, so meter, parallelism and figurative language are what make poetry, poetry in the Bible. But within the Bible you have different types of poetry just like we do in modern poetry where you have things like love songs, limericks, and nursery rhymes. And knowing what type of poetry you are reading, helps you understand the poem better. In the Bible, especially the Psalms, you have 5 major types of poetry. Let’s briefly walk through them, just to give you a taste. You’ll have a chance to explore these on your own this week through the suggested readings. 1. First is poetry of Praise & Trust, where the author lavishes praise on God and rejoicing in God’s goodness. For example, Psalm 103 begins, “Praise the LORD, O my soul; all my inmost being, praise his holy name. 2 Praise the LORD, O my soul, and forget not all his benefits.” These poems center on God for who he is and what he has done. They remind us that God is trustworthy in the past and can be trusted now and in the future. 2. Second is poetry of Lament. In many ways this is the opposite of the poems of praise at least in tone and emotions. In a Lament, the poet cries out to God when he individually or Israel at large is in great distress or has experienced great hardships. The poet may be frustrated because of himself, his people, his enemies or even God himself. Listen to the beginning of Psalm 22, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me? Why are you so far from saving me, so far from the words of my groaning? 2 O my God, I cry out by day, but you do not answer...” And so he airs out his anger & frustration, he vents to God as it were in the form of a lament. Many of the psalms are laments and there is even one whole book of the Bible that is entirely a Lament; it’s called the Book of Lamentations. 3. Third is Wisdom poetry. Next week, we’ll take a look at the wisdom genre as a whole, but for now, just know that much of wisdom writing is in poetry form including some of the psalms themselves, which extol wisdom and call us to seek to live a wise life by following God and his commands. Again, more on that next week. 4. Fourth is Israeli poetry. Now all of the poems in the Bible including the psalms are technically Israeli poetry, but what I mean here is that sections of the psalms in particular focus on things that pertained only to Israel. For example, we have Psalms that review the history of God’s saving work for Israel, psalms that are part of Israel’s covenant renewal ceremony, psalms that focus on the King of Israel, the line of David generally and their enthronements specifically, and of course you have some psalms that focus on the city of Jerusalem, which is called Zion in most of the Pslams. These poems give us a glimpse into many of the ceremonies and festivals of ancient Israel. 5. Finally, fifth are poems of Thanksgiving. Like poems of praise & trust, these psalms praise God, but usually in regard to some specific blessing in their lives. It was their way to say thank you to God for his protection, for an abundant harvest, for a new birth, for any reason one might find themselves grateful. A famous one is Psalm 136, which begins, “Give thanks to the LORD, for he is good. His love endures forever. 2 Give thanks to the God of gods. His love endures forever. 3 Give thanks to the Lord of lords: His love endures forever.” Why Poetry? I admit that a lot of what we covered so far has been pretty technical, so let’s finish the sermon by asking a simple, less technical question: why? Why would God communicate so much of his Word through poetry? Here are three reasons why God used poetry, which are the same three reasons why you should love God’s poetry as well: 1. First, poetry is easier to remember than historical accounts or laws or whatever. The meter, the rhythm, the cadence of poetry just has a way of sticking in your head and then if you add on to that that many of the Biblical poems, including all the psalms, were set to music, that these poems were actually songs, you can imagine how easy it was to remember God’s word in an age when books and literacy was scarce. But even without the music which was lost to history, it’s still easier to memorize a psalm than most other parts of the Bible. “The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want. 2 He maketh me to lie down in green pastures: he leadeth me beside the still waters. 3 He restoreth my soul: he leadeth me in the paths of righteousness for his name's sake. 4 Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil: for thou art with me; thy rod and thy staff they comfort me.” The ability to remember poetry, is why almost all of the messages God gave to his people through the prophets were given through poetry, so that the people would remember God’s warnings against them, his message of repentance and coming justice. Did you notice that last week when you were reading the prophets that it was almost all poetry? 2. Second, poetry expresses emotive truths in ways that ordinary writing just can’t. Again, the figurative writing, the parallelism help to express a certain type of truth, you just can’t get through regular prose. For example before Moses repeated the 10 Commandments and the rest of the Law to Israel in Deuteronomy 5, he said this, “Hear, O Israel, the decrees and laws I declare in your hearing today. Learn them and be sure to follow them.” Simple enough, right? But listen to how that same command is said in Psalm 1, “Blessed is the man who does not walk in the counsel of the wicked or stand in the way of sinners or sit in the seat of mockers. 2 But his delight is in the law of the LORD, and on his law he meditates day and night. 3 He is like a tree planted by streams of water, which yields its fruit in season and whose leaf does not wither. Whatever he does prospers.” The Psalm is able to take the truth of that command deeper and make it more real to us. It takes truths from the mind down to the heart. 3. Finally, third, since poetry in the Bible expresses so much emotive truth, these poems and psalms are meant to help us express ourselves to God. Are you feeling grateful? There’s a psalm for that. Are you feeling fearful? There’s a psalm for that. Perhaps you’re frustrated and angry at God, there are even psalms for that. These psalms give us an example, in many cases they even give us the very words we can use to talk to God and work through our own emotions. And I believe that that is this reason above all others as to why poetry in general and the psalms in particular are some of the most treasured and most read parts of the Bible. So much of the Bible are words from God to us, and while the poetry of the Bible is that as well, they are also simultaneously words spoken to God for our ears to hear and for our mouths and hearts to imitate. I know of no other part of the Bible that can help your prayers more than the Psalms, I know of no other part of the Bible that can help your worship more than the Psalms because these words are prayers and these prayers are the original hymnals for ancient Israel’s worship. God bless you this week as you read these wonderful ancient prayers, songs and poems. You deserve it after two weeks of the Law & Prophets, which are not the easiest things to read. May these beloved psalms ring fresh to your ears and penetrate all the way down to your hearts this week. Let’s pray.