Summary: Understanding Generation A: interim report from ESRC

advertisement

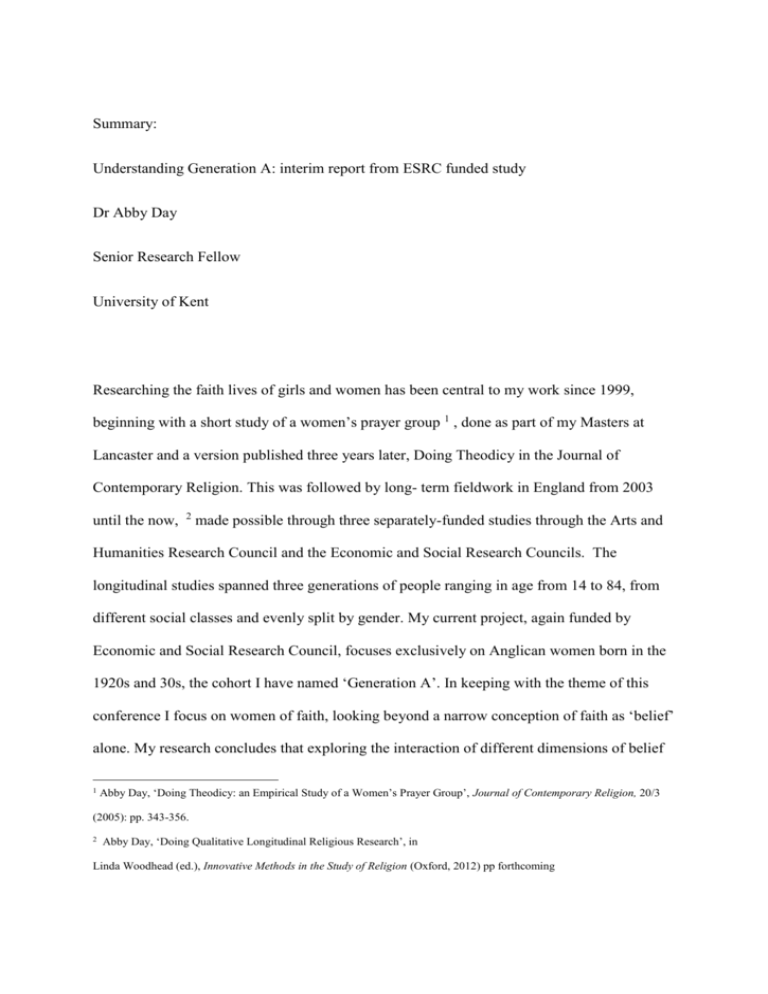

Summary: Understanding Generation A: interim report from ESRC funded study Dr Abby Day Senior Research Fellow University of Kent Researching the faith lives of girls and women has been central to my work since 1999, beginning with a short study of a women’s prayer group 1 , done as part of my Masters at Lancaster and a version published three years later, Doing Theodicy in the Journal of Contemporary Religion. This was followed by long- term fieldwork in England from 2003 until the now, 2 made possible through three separately-funded studies through the Arts and Humanities Research Council and the Economic and Social Research Councils. The longitudinal studies spanned three generations of people ranging in age from 14 to 84, from different social classes and evenly split by gender. My current project, again funded by Economic and Social Research Council, focuses exclusively on Anglican women born in the 1920s and 30s, the cohort I have named ‘Generation A’. In keeping with the theme of this conference I focus on women of faith, looking beyond a narrow conception of faith as ‘belief’ alone. My research concludes that exploring the interaction of different dimensions of belief 1 Abby Day, ‘Doing Theodicy: an Empirical Study of a Women’s Prayer Group’, Journal of Contemporary Religion, 20/3 (2005): pp. 343-356. 2 Abby Day, ‘Doing Qualitative Longitudinal Religious Research’, in Linda Woodhead (ed.), Innovative Methods in the Study of Religion (Oxford, 2012) pp forthcoming and belonging reveal a richer nature of religiosity. That was why I developed an interpretive model to focus not just on the content of belief (usually dealt with by sociologists by asking short questions such as ‘do you believe in God’) but belief’s resources, practices, salience and functions. To study belief longitudinally, new elements of place and time were incorporated. This holistic, organic, multi-dimensional framework developed the research beyond standard sociological techniques to an enhanced anthropological approach introducing a performative, dynamic element. This process, which I termed ‘performative belief’, refers to a neo-Durkheimian construct where belief is a lived, embodied performance brought into being through action. Within a social context are social relationships: performative belief plays out through the relationships in which people have faith and to which they feel they belong. Belief in social relationships is performed through social actions of both belonging and excluding. Applying this theory to gender is instructive. Women in Euro American countries are apparently more religious than men, and older women more religious than younger women. That generalised statement seems to be supported by large-scale quantitative data on Christianity in the UK: about 40 % of Church of England monthly attendees are women aged 60 or over - twice the number of men of a similar age. 3 Older women are represented disproportionately: 4 per cent of the general population attends the Anglican Church regularly; about 10 per cent of women over 60 attend and less than 2 per cent of women under 60. Evidence suggests that this is a unique generation that will not be replaced: women under the age of 60 attend church much less often than their mothers and their participation has not been increasing over time. Such behaviour sometimes leads scholars to conclude that women are more religious than men. That is claim supported by some research, as described above, but leaving a counter-argument unexplored: if, indeed, women are ‘more religious’ 3 British Social Attitudes: the 24th Report, (London: Sage, 2008). than men, how do we account for widespread evidence that men exclusively occupy the most senior strata of religious institutions, and are permitted, unlike women, to be priests, imams, or monks in most religious institutions. Feminist inroads have been made in liberal forms of Judaism and Christianity, but these have been recent, hard-won battles that have caused schisms on an international scale as men have resisted such intrusions. Religious power and authority has been and generally remains a male domain. When, therefore, people suggest that women are more religious than men they must be restricting their analysis to certain behaviours and kinds of lay religiosity. This lack of a definition of what is construed as religious and what may be explained by gender may speak to a wider unease about gender in the sociology and anthropology of religion. 4 Only quantitative surveys asking such limited and thin questions as, for example, ‘do you believe in God’ provide evidence of more female than male. I will argue here that not just qualitative research but in particular rich ethnographic research is necessary to reveal other explanatory values, such as relatedness, power structures, and sociality, which may better explain gender discrepancies. What may be at stake is the kind of religiosity that is valued and then accorded to men or women. 4 Linda Woodhead, ‘Feminism and the Sociology of Religion: from Gender-blindness to Gendered Difference’, in Richard Fenn (ed.) The Blackwell Companion to Sociology of Religion (Oxford, 2001), pp. 67—84; Day, Theodicy: pp. 343—356; Fiona Bowie, The Anthropology of Religion (Oxford, 2006); Fenella Cannell (ed.), The Anthropology of Christianity (Durham and London, 2007).