Text S2. - Figshare

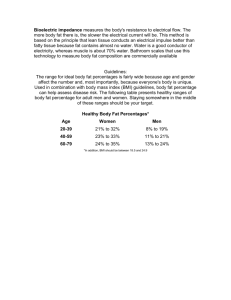

advertisement