Chapter 30

advertisement

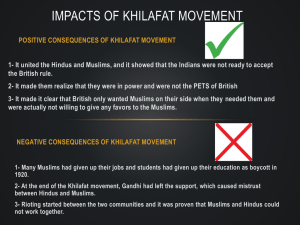

The Tandon Family at Partition About the Document Despite the protests of figures such as Gandhi, the partition of British India into the independent nations of Pakistan and India had become necessary due to the increasing inter-sect rioting and violence common in 1946-1947. Southern India, with a fairly insignificant Muslim population, felt little immediate impact from the split, but this was not the case in the north. Most Muslims lived in the northern provinces such as the Punjab. Both Indian and Pakistani leaders pledged to treat minority religious practitioners fairly and equitably. After partition, however, violence quickly returned, as Hindus attacked Muslims still in India and Hindus in Pakistani territory were harassed. What followed were two mass migrations, wherein Muslims migrated out of India and into the territories designated for Pakistan and Hindus fled into India from Pakistan. The partition was especially traumatic for those involved in the migrations. Many were forced out of the homes and occupations their families had maintained for centuries, while others initially refused to leave and were rarely safe for long. Prakash Tandon writes in Punjabi Century about some of his family’s experiences during this period. The Document DEAR PRAKASH, Come and get us out before it is too late. While the fading paper flags of the independence celebrations were still waving, the horror of partition broke on us suddenly one day when a post-card arrived from Uncle Dwarka Prashad. It contained this single line. With my younger brother, who was also settled in Bombay, I had discounted the first rumours, while Government tried to tone down the press hand-outs. No one wanted to spoil the music of freedom still in the air. But every day the news became graver, and uncle's post-card told us that the end had come. In June of 1947, when partition was announced, most Hindus and Sikhs had accepted it fatalistically. 'We have lived under the Muslims before, then under the Sikhs and the British, and if we are now back under Muslim rule, so what? We shall manage somehow, as we have managed before. Nowadays governments are different, they give you some rights, they have to listen to the people!' Fortified by such arguments, people decided to stay where they were and face the change. In July things began to look menacing, but few thought of leaving. There were sporadic attacks on Hindus and Sikhs, but they were mostly looked upon as signs of another riot. The turn had come of the Punjab, where people during the war years had prided themselves on living in peace while the rest of the country shook with the ugly outburst of Hindu-Muslim violence. As things worsened, father wrote to say that he considered it pointless to leave the house. Even if there was real trouble he would be safe, because he had so many Muslim friends and neighbours. Who would want to harm an old man, semi-paralysed by a stroke? Besides, he was so comfortable with his faithful Chattar Singh, who was on such good terms with everybody, Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs alike, to look after him. In August law and order of ninety years came to an end. Elementary civil protection, taken for granted the week before, ceased. Chatter Singh felt that his own family would prove a burden if he suddenly had to leave; and to take care of father would be an added problem. So he appealed frantically to our neighbours to persuade father to go away for a while, till things improved. He was going to move his wife and children to the safety of Amritsar, now across the border. My elder brother wired from Bihar that father must leave, and reluctantly he agreed, whereupon Chattar Singh hurriedly packed him off. Many others were sending their women and children and old people away. Like everyone else, father thought he was only going for a short time, till the riots subsided. Uncle Dwarka Prashad had remarried some years after Savitri's death and had permanently settled in Gujrat. Uncle had always been tough and fearless, and easily persuaded to fight. He was greatly respected by all communities, and most of his practice came from Muslim litigants in the district. Everyone assured him that he could safely stay, no one would touch him and his family. He wanted to believe in their assurances even as he saw the trickle of exodus gather volume. These others thought it wise to go away for a while; they would all return when everything was calm again. The thought that this was a going away for ever never crossed anybody's mind. A calamity might cause temporary uprooting, but afterwards you came back to what had always been your home. One day, a train crammed with two thousand refugees came from the more predominantly Muslim areas of Jhelum and beyond. At Gujrat station the train was stopped, and the Muslims from the neighbourhood, excited by the news of violence in East Punjab, began to attack and loot. There was indescribable carnage. Several hours later the train moved on, filled with a bloody mess of corpses, without a soul alive. At Amritsar, when the train with its load of dead arrived, they took revenge on a trainload of Muslim refugees. Six million Hindus and Sikhs from the West Punjab began to move in one dense mass towards safety, and from the east of the border a similar mass movement was under way in the opposite direction. Muslim friends came to uncle late one night and said with tears in their eyes that they were unable to offer him protection any longer. The family must move at once, before dawn! Dwarka Prashad now saw it only too well that they had to go away, not for a few days, but for ever. He had in fact been expecting it since the day of the massacre at the station, but the problem had been how to get out; and it was then that he had sent the post-card. His friends rushed to an Indian military evacuation convoy that had arrived the same evening, and brought a truck. They heaved a sigh of relief as uncle and his family, with two suitcases and a few blankets, drove away. On the Grand Trunk Road their truck joined an unending line of military and civil trucks and cars, bullock carts and tongas, people on horseback, and carried on shoulders. In its long history of over a thousand years this road had never seen such a migration. As dawn was breaking, they caught the last view of Gujrat through the shisham trees by the road. Partition changed the course of many lives which would otherwise have run in their familiar channels. AT PARTITION we three brothers were already scattered outside the Punjab. For us there was no more Punjab. Many refugees settled in East Punjab, but to us and many others, it was all over when the West Punjab went, and home was now where we earned our living. Those amongst the refugees who did not find an immediate footing in the East Punjab went all over India. One could not help admiring their courage and enterprise. Simple people, who had probably never been further than fifty miles away from their homes, set off in all directions and landed up in places they had never heard of. My younger brother and I decided to forget the Punjab and regard Bombay as our home. We built two small houses next to each other, at the foot of Pali Hill in an area of largely Christian population. We had already lived in this area for a number of years and made many friends. Now, instinctively, we began to throw the roots deeper, and soon we were invited to their weddings and christenings and attended their funerals. They found our Punjabi ways, or Indian ways, as they called them, quaint. Our children went to the local schools where they learned English while they spoke Hindi at home. They never learned Punjabi. Analysis Questions 1. What did many Punjabis say after partition was the reason they planned on staying in their homes? 2. What happened to the train full of Hindu refugees as it was passing through a Muslimdominated area? 3. Where do Tandon and his younger brother finally settle? 4. Which relative does Prakash Tandon primarily speak of in this excerpt? 5. Why didn’t Tandon’s father wish to leave the Punjab at first?