The partition of India and retributive genocide in the Punjab, purposes

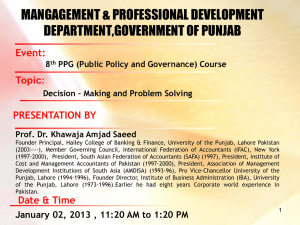

advertisement