Su-Hie Ting

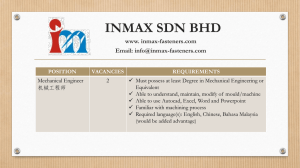

advertisement

Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference of Teaching and Learning (ICTL 2011) INTI International University, Malaysia GETTING PUBLISHED: STRENGTHENING THE INTRODUCTION AND DISCUSSION SECTIONS Su-Hie Ting Universiti Malaysia Sarawak, Malaysia (shting@cls.unimas.my) INTRODUCTION With the push for research output brought about by university ranking, academics are forced to do research and publish. Many embark on writing conference papers but some do not progress to journal papers. To get published, research articles need to contribute to the existing body of knowledge, employ appropriate and sound methodology, fit the journal and be well-written (Daft, 1985; DeMaria, 2007; Holschuh, 1998). However, conference papers may not be subjected to the same exacting standards. To help academics acquire the necessary skills to get published, some universities conduct research methodology and research writing workshops. Others make arrangements for experienced researchers to mentor novice researchers. This is part of the lifelong learning endeavour which may not produce expected outcomes if a core misconception is not addressed -- the façade of doing research when it is merely amassing data. Sometimes the data are collected to solve a local problem, replicate an existing study or to take up on somebody’s idea. At other times, the data are just available. The problem driving the research is not anchored in literature, and hence the research question does not have a wider significance beyond the immediate context of the study. Hence, the chances of having the manuscript accepted is reduced because journals “publish high-quality, original and state-of-the-art papers describing theoretical and empirical aspects that can contribute to advance … understanding” of certain phenomena (International Journal of Multilingualism, 2011). Given that the science of the research is sound, the acid test is often the ability of the researchers to show the value of their findings to the body of knowledge. PURPOSE OF WORKSHOP The workshop aims to increase the chances of getting published in indexed journals by comparing the quality of conference papers and journal papers before addressing the organisational structure of the Introduction and Discussion sections of research articles. The workshop also broaches collaborative strategies to motivate academics to submit research articles. METHOD The corpus consisted of 50 research articles from eight Malaysian journals in the field of applied linguistics, with public online access. These journals were published by Malaysian universities and a professional association from the year 1995 to 2007. Only research articles reporting empirical studies were included in the corpus. Articles dealing with literary text analysis, reviews and opinions which have not been empirically tested were not selected. In addition, the selection focused on research articles written by non-native English speakers. For this, an inference was made based on the names of the authors and the institution to which they are affiliated. This cannot eliminate native English speaker input on the research articles and misjudgments on the native or non-native English background of the authors. In the event of uncertainty, the research articles were not included in the corpus. 1 Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference of Teaching and Learning (ICTL 2011) INTI International University, Malaysia The research articles in the corpus were analysed based on checklists in Tables 1 and 2. The framework for analysis of the Introduction section was adopted from Swales’ (2004) revised Creating-A-Research-Space (CARS) model (Table 1) whereas the framework for analysis of the Discussion/Conclusion section was adopted from Yang and Allison (2003) (Table 2). COMMON WEAKNESSES OF INTRODUCTION SECTION Table 1 showed that there was a review of previous research in all the research articles analysed (119 occurrences in 50 articles) but only 27 of them presented a gap for the study. In Creating-A-Research-Space (CARS) model of Introduction conceptualised by Swales (2004), establishing a niche for the study (Move 2, M2) is the second essential step after establishing the research territory (Move 1, M1) and before announcing the present research (Move 3, M3). The Introduction generally consisted of a brief mention of related studies in the research area. A cursory mention of the unavailability of similar studies in the same context is used to justify the need for the study but the uniqueness of the context is not highlighted to show the necessity of studying the phenomenon in that setting. Possible reasons preventing the writing of good Introduction sections include cultural background (see Kanoksilapatham, 2005) and deficits in knowledge of the research area. Table 1. Frequency of moves and steps in Introduction section of research articles analysed Moves Steps Frequency in 50 articles 35 48 119 Average per article 0.7 0.96 2.38 Move 1 (M1): Establishing a research territory Move 2 (M2): Establishing a niche Move 3 (M3): Presenting the present work S1: Claiming centrality S2: Making topic generalisation(s) S3: Reviewing items of previous research S1A: Indicating a gap S1B: Adding to what is known S2: Presenting positive justification (optional) 27 4 39 0.54 0.08 0.78 S1: Announcing present research descriptively and/or purposively S2: Presenting questions or hypotheses (optional) S3: Definitional clarifications (optional) S4: Summarising methods (optional) S5: Announcing principal outcomes S6: Stating the value of the present research S7: Outlining the structure of paper 59 1.18 47 18 8 3 11 5 0.94 0.36 0.16 0.06 0.22 0.1 COMMON WEAKNESSES OF DISCUSSION SECTION Discussion of the findings is usually found in the concluding section of the research articles, under various headings (e.g., Results and Discussion, Discussion, Conclusion). Analysis of the concluding section of the research articles using Yang and Allison’s (2003) framework 2 Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference of Teaching and Learning (ICTL 2011) INTI International University, Malaysia showed that only 23 out of 50 articles contained the three obligatory moves: Summarise the study (Move 1, M1), Evaluate the study (Move 2, M2), and Deductions from the research (Move 3, M3). The research articles analysed in this study are often concluded with a summary and pedagogical implications but seldom with an in-depth discussion of how the findings enhance understanding of the research problem. Table 2 shows that 49 articles summarised the main findings and relatively more articles elaborated on the pedagogical implications of the findings (32 articles) compared to indicating significance of the findings to the body of knowledge (22 articles). This style presents the findings as isolated from the body of knowledge. In fact, lexico-grammatical means are used in research articles to argue and lead the reader from the proof represented by the data to making the final claim of proof (Parkinson, in press). Table 2. Frequency of moves and steps in Conclusion/Discussion section of research articles analysed Moves Steps Move 1 (M1): Summarising the study Move 2 (M2): Evaluating the S1: Indicating significance study S2: Indicating limitations S3: Evaluating methodology Move 3 (M3): Deductions from S1: Recommending further the research research S2: Drawing pedagogical implication Frequency in 50 articles 49 Average per article 0.98 22 12 4 11 0.44 0.24 0.08 0.22 32 0.64 COMPARISON OF CONFERENCE AND JOURNAL PAPERS This comparison rests on three assumptions: (1) the papers presented at conferences report preliminary work that is not ready to be published in journals; (2) the conference papers are written by novice researchers who are not familiar with the standards of journal papers; and (3) the papers are intentionally written as conference papers by seasoned researchers. For these researchers, if they had written a paper that is of journal paper quality, they would have submitted it to a journal for consideration instead of sending it to a conference. The overall structure of the conference and journal papers does not vary but there are differences in the attention paid to establishing a gap for the study and discussing the significance of the findings to the field. In other words, the main difference lies in the Introduction and Discussion/Conclusion sections of the research articles. The Methods and Results sections are usually similar, with perhaps more justifications of the data collection and analysis procedures and more thought through interpretations of the results for journal papers. These differences are illustrated with excerpts from a conference paper on teacher education and a journal paper on code-switching, beginning with the Introduction section and then moving on to the Discussion/Conclusion section. 3 Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference of Teaching and Learning (ICTL 2011) INTI International University, Malaysia COMPARISON OF INTRODUCTION SECTION In Excerpt 1 taken from a conference paper on language teacher education, arguing whether it is language proficiency or pedagogical knowledge that is more crucial for one to be able to teach English well. The 713-word Introduction spread across five paragraphs moves from general area of teacher education and teacher quality and the essential components of teacher education courses to the specific area of language teacher education and singles out the trainee teacher’s language proficiency as a variable to study. A practical justification on the grounds of the trainee teacher’s engagement with the language teacher education programme is offered before the purpose of the study is stated. The Introduction makes claims about the relevance of the topic for investigation but does not cite related literature on the debatable issue that is of interest. The current state of knowledge on the research problem is not presented. Instead the Introduction includes an unrelated paragraph on the traditional and recent English language teaching approaches. The Introduction appears to be written for practitioners in language teaching and offers background information on the topic. However, the Introduction does not situate the study in the context of foregoing studies on the issue of the quality of English teachers. Without a review of the related literature on the research problem, there is no empirical evidence to establish a niche for the study. Using logical reasoning may suffice for conference papers but not for journal papers. Excerpt 1 Ting, S. H., & Mahanita Mahadhir (2006, May 8-10). What makes a good English teacher: Language proficiency or teaching methodology? Paper presented at 6th Malaysia International Conference on English Language Teaching (MICELT 2006), Melaka. Introduction The interest in teacher quality stems from the awareness that “teacher effectiveness accounts for the largest variation in student achievement, more so than what the schools do (e.g. schools might introduce smaller classes or more reading programmes)” (Darling-Hammond cited in Ornstein, 2003, p. 138; see also Rice, 2003), excluding the composition of the school body (Goldhaber, 2002). Darling-Hammond points out that “teachers who are fully prepared and certified are more effective with students than teachers without full preparation” (cited in Ornstein, 2003, p. 138). In other words, teacher preparation programmes do play a role in ensuring teacher quality. [4 paragraphs beginning with these topic sentences: The requirements and emphasis of teacher preparation programmes has varied through the years but two essential components in teacher training are subject matter knowledge (content) and pedagogical skills In the context of language teaching, teacher education programmes include: (1) subject matter courses that build up knowledge of the language system; (2) general methodology courses; and (3) specialised language teaching methodology courses. In addition to knowledge of the language system and language pedagogy, another factor relevant to the discussion of what makes good language teachers is language proficiency. Nowadays, the functional view of language prevails whereby language Teacher education and teacher quality Justifying significance of the study 4 Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference of Teaching and Learning (ICTL 2011) INTI International University, Malaysia is viewed as a system of signs to make meanings in context.] Do teacher trainees in the Teaching of English as a Second Language (TESL) programme believe that they need these kinds of knowledge and skills for them to be good English teachers? If they do not, then it is likely that they may not Purpose of be willing to engage with courses in the TESL degree programme and Study internalise what is taught. The teacher education programme would merely be a certification process. This study was conducted to find out a) the pre-service and in-service teacher trainees’ perspective on the importance of language proficiency and TESL training in making them good English teachers, and b) to find out whether there is a relationship between mastery of language and methodology. In this study, TESL training includes both subject matter knowledge and pedagogy. Now compare Excerpt 1 with Excerpt 2 which is published in an indexed journal. For this particular Introduction, the purpose of the study appears in the first paragraph, following the recent trend that is apparent in some research articles. Following the announcement of the present research, the Introduction begins with the importance of having proficiency in the instructional language particularly for students from multilingual backgrounds before citing literature to show how the role of language in content and language lessons differs. Then the Introduction brings in the idea that code-switching is a way out for content and language lessons whereby students are less proficient in the instructional language. The final paragraph in the 1,314 word-Introduction is where an argument is made to justify a need for the study. The argument starts by singling out a particular function of code-switching, reiteration, and makes a connection to other research areas where the phenomenon is referred to as reformulation or translation. Lack of research on the use of reiteration is justified with a claim that previous studies in sociolinguistics have examined the types and functions of codeswitching in facilitating classroom interaction and learning but only in general. Then specific findings on the use of reiteration are provided to show the pros and cons of the practice. This builds up to a justification that an integrated sociolinguistic and language teaching perspective can offer new insights into the use of reiteration for both content and language lessons. Compared to the Introduction in conference papers, much more work goes into the establishing a niche for the study. The extensive available literature, sometimes disparate, needs to be brought together in a coherent manner to offer a somewhat new perspective on a research problem, which may have been well-studied. Purpose of study Excerpt 2 Then, D. C. O., & Ting, S. H. (2011). Code-switching in English and science classrooms: More than translation. International Journal of Multilingualism, 8(3). DOI: 10.1080/14790718.2011.577777 (Indexed by Scopus) Introduction This paper presents some of the findings from a larger study that examined code-switching in the classroom discourse of English and Science teachers in Malaysian secondary schools. The focus of the paper is on the reiterative function of code-switching and the forms it takes in a multilingual classroom setting. Code-switching refers to the use of more than one code or language in the course of a single speech event (Gumperz, 1982). The 5 Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference of Teaching and Learning (ICTL 2011) INTI International University, Malaysia code-switching may be minimal involving single words or bigger chunks of language. Singles out reiteration Lack of studies on this function of code-switching [4 paragraphs beginning with these topic sentences: Language is central to the construction of meaning in the classroom. The role of language in content and language lessons differs. While studies are consistent on the usefulness of bilingual content teaching, code-switching in language classrooms is a debatable issue. However, research indicates that code-switching can also be an invaluable support for language learning to take place when the target language is a barrier for learning (e.g. Greggio & Gil, 2007; Reini, 2008).] Thus far, from the review of related literature, differences in the types and functions of teacher code-switching in content and language classrooms are not clearly evident. One particular function of codePros and cons switching that has been highlighted in many of these studies is reiteration, of reiterating sometimes referred to as reformulation (e.g., Setati, 1998) or translation or translating (e.g., Zabrodskaja, 2007) depending on the framework of analysis. These to another studies focus on the types and functions of code-switching in facilitating language classroom interaction and learning in general. However, code-switching, or more commonly referred to as translation, is a contentious issue in language Justification of teaching literature. On the one hand, translation can lower the chances of the benefits of error because students know exactly what the sentences mean studying (Cunningham, 2000), students also understand the cultural-bound meanings reiteration and hidden agenda of the texts through revision, rewriting and redrafting of from a the translation (Sima & Saeed, 2010). In addition, translation also enables perspective students to discover different vocabulary and style of texts of the same that integrates genre in the source language and target language (Petrocchi, 2006). On the sociolinguistics other hand, Cunningham cautioned that overuse of translation prevents and language students from thinking, reading, and writing in the target language because learning the translation is available, and translation could end up singling out students when not all students share the same mother tongue. The caveat is that alienation of students who do not understand the language used in the translation is less likely to occur in multilingual contexts where students share a common language such as the national language in the case of Malaysia, Brunei Darussalam and Indonesia. Nevertheless, studies on codeswitching for reiteration of messages and translation have largely been independent of each other. Situating a comparison of translation and reiteration in the context of Gumperz’s (1982) model of conversational code-switching would yield insights into how code-switching facilitate learning of content subjects and languages in educational settings where students are from diverse linguistic groups. 6 Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference of Teaching and Learning (ICTL 2011) INTI International University, Malaysia COMPARISON OF CONCLUSION SECTION The concluding section which comes after the Results section needs to perform the task of summarising findings and staking a claim that the study has made some significant contribution to the field and succeeded in filling the gap that is described in the Introduction, albeit partially. The contribution is qualified by mentioning some unavoidable limitations, followed by suggestions for further research to address these limitations. Depending on the scope and readership of the journal, there may be a need to provide practical applications of the findings. Having said that, in conference papers, the concluding section usually consists of a summary of findings and pedagogical implications of the findings for papers which are related to teaching and learning (Excerpt 3). As far as this particular conference paper is concerned, the goal of the paper set out in the Introduction section has been achieved but this kind of conclusion is unacceptable for journal papers. Excerpt 3 Ting, S. H., & Mahanita Mahadhir (2006, May 8-10). What makes a good English teacher: Language proficiency or teaching methodology? Paper presented at 6th Malaysia International Conference on English Language Teaching (MICELT 2006), Melaka. Conclusion We had hoped that all the teacher trainees would express views in support of the important roles of both methodology and language proficiency in good language teaching. However, only a third of them believe in the value of both. In dire circumstances when there is a shortage of English teachers, those who view training as more important rationalised that lack of training can be fixed with in-house training and short courses. Those who equate good English teachers to being good users of the language reasoned that proficiency could be developed over time provided they are intrinsically motivated. In view of these results, we question the necessity of TESL degree programmes. Answer to the research question Implications on student engagement in language teacher education programmes Considering the small proportion of teacher trainees who believe in the importance of TESL training and language proficiency, we postulate that student engagement with pedagogy courses and subject matter courses is less than desirable. Given this, what is taught may not be internalised and these teacher trainees may graduate with the beliefs and views they held of what effective English language teaching before the TESL training. If indeed the Pedagogical views of teacher trainees in this study are representative of the population, then implications the TESL training has not achieved an important goal to make the trainees of findings realise why they need to be trained and why they need to be good in the language. However, as providers of the language teacher preparation programme, we offer several suggestions for benchmarking quality practices: 1. Putting the issue of what makes good English teachers for open discussion in TESL courses; 2. Ensuring better quality courses through preparation of course portfolio 7 Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference of Teaching and Learning (ICTL 2011) INTI International University, Malaysia and review of courses by peers and external board of study; 3. Changing existing practices of lecturers such as high tolerance towards poor mastery of language teaching methodology and the language itself; and 4. Putting in place policy and administrative practices that recognise the value of TESL training and language proficiency. Excerpt 4 is taken from a journal paper. When the manuscript was initially submitted for review, the concluding section looked like that of a conference paper. A reviewer commented that “The discussion (as opposed to description) should be presented as a summary of findings and the larger significance explained.” The two brief paragraphs were expanded to a 4-paragraph 909-word conclusion as shown in Excerpt 4. Paragraph 1summarises the findings on the functions of code-switching. Paragraphs 2 and 3 highlight notable findings and situate them in the literature. Paragraph 3 goes on to use the local setting of the study to show the sociolinguistic implications of teacher’s tendency to reiterate messages in the national language. The final paragraph pulls together pros and cons of code-switching to make a final claim that code-switching facilitates learning and is natural language behaviour in a multilingual setting. To write an acceptable discussion, the results need to be seen from the broader perspective of the research problem. Novice researchers may find it useful to reread related research articles to help them situate the findings in the body of knowledge and stake a claim on how the findings have filled in the gap of knowledge. It may be useful to take on the role of the devil’s advocate and ask the “so what” question to frame the central contribution of the study. Excerpt 4 Then, D. C. O., & Ting, S. H. (2011). Code-switching in English and science classrooms: More than translation. International Journal of Multilingualism, 8(3). DOI: 10.1080/14790718.2011.577777 Conclusion Within the context of code-switching in science and English-as-a-second-language classrooms in Malaysia, we have examined how languages are juxtaposed for various functions of code-switching. The code-switching is mainly between English, the language of instruction, and Bahasa Malaysia which is the national and official language of Malaysia. On the basis of Gumperz’s (1982) model of conversational code-switching, the classroom data revealed that the main functions of teacher code-switching are reiteration and quotation. Most of the reiterations are message repetitions involving words, concepts or instructions in Bahasa Malaysia. Repeated reiterations mark the salience of the information whereas single reiterations involve mainly meaning of words. When the form of the reiterations was analysed, it was found that about half of them are direct translations aimed at ensuring conceptual understanding of content or student compliance in classroom activities. The code contrast captures students’ attention and helps to maintain the planned structure of the class, as found by Greggio and Gil (2007). In addition, the alternation of languages in repeated reiterations or quotation-reiteration sequences provide evidence for the use of the sandwich technique (Butzkamm & Caldwell, 2009) to ensure comprehension in which an initial utterance in English is reiterated in Bahasa Malaysia, and again in English. The English teachers under study were found to code-switch more frequently than the 8 Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference of Teaching and Learning (ICTL 2011) INTI International University, Malaysia science teachers. Furthermore, the English teachers also reiterated messages in Bahasa Malaysia more frequently than the science teachers. This pattern of code-switching for informational exchange is surprising given that in language lessons, students are not only learning the content but the language itself. The transcripts showed that the science teachers were less dependent on code-switching to make meaning because they could use examples and realia to explain scientific concepts such as volume and processes such as digestion. By so doing, the teachers reformulated the scientific terms and concepts in everyday language and circumvented the need for translation. On the other hand, the English teachers tended to translate terms into Bahasa Malaysia as a short-cut in the meaning making, particularly for vocabulary items. It seems that using translation to overcome the barrier posed by unfamiliar vocabulary is also the reason for code-switching in other studies (e.g., Flyman-Mattsson & Burenhult, 1999; Zabrodskja, 2007). The code-switching reduces the opportunity for both the teacher and students to negotiate meaning using available linguistic resources, thereby compromising their ability to develop strategic competence in using English for functional communication. However, it can be argued that since language learning is more than just acquiring the building blocks of the language, the time saved through code-switching can be better spent on developing other language skills which need to be learnt in a school year. The frequent use of code-switching found in this study, about once in every two to three minutes, indicate the important role of other languages, particularly Bahasa Malaysia in facilitating learning. However, the extensive code-switching has socio-political implications. Code-switching reinforces the dominance of certain languages, particularly the standard national and official language (García, 1993). In the Malaysian context where the study was conducted, switching to Bahasa Malaysia for announcing school programmes and ministry directives reinforces Bahasa Malaysia as the language of power. Because of its status as the official language, teachers who are not members of the ethnic group in power also feel more comfortable switching to Bahasa Malaysia than to languages of the less numerically dominant groups such as Mandarin Chinese in the classroom. In the context of the classroom, teacher code-switching to Bahasa Malaysia affirms the importance of this language in the education of the students. These are positive implications in the context of the national language policy. In general, the findings on the facilitative role of code-switching in aiding student comprehension concur with other studies on code-switching in either content (e.g., Setati, 1998) or language classrooms (e.g., Greggio & Gil, 2007; Liebscher & Dailey-O’Cain, 2005). The use of the students’ first languages provides a communicative resource to facilitate learning when students lack proficiency in the language of instruction. The scaffolding offered by the students’ first languages helps guide students through the learning process (García, 1991). In reality, the need for effective communication in the classroom is so strong that teacher code-switching takes place despite the existence of monolingual language policies on the medium of instruction. Seen from the perspective of the implementation of language policies, code-switching practices by the teacher is a compromise in providing target language exposure in language classrooms and deprives students of the opportunity to negotiate meaning in the language of instruction for content subjects. When code-switching is an alternative, students and teachers alike are not required to develop strategic competence in using their available linguistic resources to make meaning. On the other hand, by disallowing code-switching in the classroom, the learning of students would be affected if they are not proficient in the language of instruction. Jacobson (1981) supports the use of functional codeswitching in transitional bilingual classrooms. Citing Krashen (1982) on the importance of 9 Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference of Teaching and Learning (ICTL 2011) INTI International University, Malaysia comprehensible input to second language acquisition, García (1993) advocates that “in some ways code-switching may facilitate English language acquisition by providing a context from which to infer meaning” (p. 32). In addition, code-switching is a natural phenomenon of language use in settings when teachers and students share the same languages (Simon, 2001). The classroom is a microcosm of the larger speech community and the multilingual repertoires of the students is a communicative resource that can be used to help them engage with the curriculum. CONCLUSION The ability to situate research findings in a web of knowledge presumes familiarity with developments in the field, derived from extensive and intensive reading of related literature and extended work in the research area. Both require an investment of time, and some academics may opt for the quicker route of producing conference papers. In order for academics to see value in journal publications, collaborative strategies are needed at many levels. At the level of peers, friendly competition may push some to publish journal papers. Trusted peers can also act as the devil’s advocate to question the significance of the findings. However, in the face of time constraints due to teaching commitments, support at the level of the university management is needed for the research culture of publishing in journals to be established. When the rod (publish or perish) cannot really be enforced, the carrot (publish and be rewarded) is a better alternative. Administrative support in research activities and funding as well as recognition in the form of merit-based promotion and short-term incentives for publications is important to inculcate a research culture before academics can publish as a way of life. Collaborative strategies that extend beyond the university to the industry include research funding and access for industry-driven research. Acknowledgement: The author wishes to thank Lim Swee Hoon and Tang Ping Wei for analysing the data for the Introduction and Discussion sections respectively. REFERENCES Daft, R. L. (1985). Why I recommended that your manuscript be rejected and what you can do about it. In L. L. Cummings & P. J. Frost (Eds.), Publishing in the organisational sciences (pp. 193-204). Homewood, IL: SAGE Publications. DeMaria, A. (2007). How do I get a paper accepted? Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 49(15), 10.1016.j.jacc.2007.03.017 Holschuh, J. L. (1998). Why manuscripts get rejected and what can be done about it: Understanding the editorial process from an insider’s perspective. Journal of Literacy Research, 30(1), 1-7. International Journal of Multilingualism (2011). Aims & Scope. Retrieved from http://www.tandf.co.uk/journals/rmjm 10 Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference of Teaching and Learning (ICTL 2011) INTI International University, Malaysia Kanoksilapatham, B. (2005). Rhetorical structure of biochemistry research articles. English for Specific Purposes, 24, 269-292. Parkinson, J. (in press). The Discussion section as argument: The language used to prove knowledge claims. English for Specific Purposes. Swales, J. M. (2004). Research genres: Explorations and applications. Cambridge. Cambridge University Press. Yang, R. Y., & Allison, D. (1990). Research articles in applied linguistics: Moving from results to conclusion. English for Specific Purposes, 22, 365-385. BIODATA Dr Su-Hie Ting teaches at the Centre for Language Studies, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak. She graduated from University of Queensland with a Ph.D in Applied Linguistics in 2001. She has published on language use and attitudes, academic and research writing as well as English language teaching. 11