Primary and Elementary Programs

advertisement

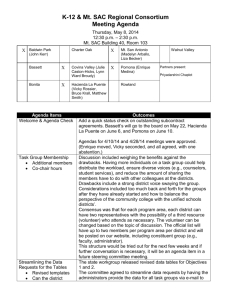

The Emerging Three-Tier System in K-12 Education Finance in BC: A Policy Study Draft: Please do not distribute or quote without the permission of the authors Wendy Poole Associate Professor Department of Educational Studies University of British Columbia wendy.poole@ubc.ca Gerald Fallon Assistant Professor Department of Educational Studies University of British Columbia gerald.fallon@ubc.ca Abstract: This paper examines increasing privatization of education in the province of British Columbia, Canada. Using analysis of policy documents and financial records from government departments and written critiques from non-governmental organizations such as teacher unions, other public sector unions, and stakeholder groups in BC, the paper critically examines education policy that has enabled the emergence of private sources of revenue (tuition fees and for-profit revenue) and the establishment of school choice and education program choice that, the authors argue, are leading to the development of a three-tier education system in British Columbia. The article concludes with a discussion of implications related to equity and social justice in education. Introduction Canadians have had an historical acquaintance with a two-tier education system and British Columbia (BC) is no exception. Private and public schools have co-existed in BC for a century and a half. The percentage of BC school children attending private schools (called “independent schools” in BC) has doubled over the past two decades (Federation of Independent School Associations, 2012), marking a trend toward privatization of K-12 education. Another form of privatization is creeping into the system -- increasing privatization within the public education system. Facilitators of this latter 1 trend are market-driven and enrolment-based forms of funding, school and program choice policy, and structural funding shortfalls. Since 2001, the BC government has initiated policies designed to download more costs to school districts and increase competition between public schools, including: opting not to finance inflationary and new costs to school districts; moving to a per-pupil Block Funding formula that makes revenue dependent upon the number of students enrolled in the school district; removing boundaries between catchment areas and allowing parents to choose the schools where they enroll their children; and enabling school boards to create ‘school district business companies’ that operate at arms length. Schools and districts have responded by competing with each other to create special programs to attract students and thus generate a greater share of enrolment-based government grants. They have established other programs with fees attached. These policies, we argue, introduce increasing levels of privatization1 within school districts. Such privatization is problematic as it enables systemic funding and programming inequities to grow between schools and school districts since their respective capacity for participating in a competitive education market-place varies substantially. Using document analysis, this paper will elaborate on the facilitating factors, critically examine the education policy direction, and discuss implications related to education programming, levels of funding, and equity/social justice. The first part of our paper introduces the theoretical and contextual framework, highlighting common policy 1 Privatization refers to a process that represents a move toward competition for government and nongovernment funding under conditions when markets should be expected to work efficiently in terms of choice of suppliers-schools and distribution of public and private sources of funding (Ball, 2007; Starr, 1989). 2 themes that emerged as part of the phenomenon of globalized neoliberalism. The second part describes aspects of government policy (structural shortfalls; school and program choice; enrolment-based public funding; and market-driven private funding) that have shaped an entrepreneurial approach to public school finance. The third part of our paper discusses issues of emerging inequities of funding and educational programming among public school districts in BC that, we argue, give rise to a three-tier education system in BC. Theoretical and Contextual Framework: Globalization and Neo-liberalism The phenomenon of competition for governmental and non-governmental sources of funding needs to be viewed in the context of the rise of globalized neo-liberal policy. Globalization refers to “the rapid movement of ideas, goods, and people around the globe, radically transforming relations among people and communities across national boundaries” (Rizvi, 2008, p. 63). Rizvi adds: “Through major advances in information and communication technologies, educational ideas and ideologies now circulate around the world at a more rapid rate resulting in global educational policy networks which are often more influential than local political actors” (p. 63-64). Through globalization, Rizvi argues, education policy has displayed a “major shift to neo-liberal policy thinking, manifested most clearly in privatization policies, and in policies that assume the validity of market mechanisms to solve most of the crises facing nation-states and civil society” (p. 64). The latter quote from Rizvi is reflected in the BC policy landscape over the past decade, where neo-liberal policy, increasing privatization, and market mechanisms are transforming public education. 3 Olssen (1996) details the differences between liberalism and neo-liberalism as follows: Whereas classical liberalism represents a negative conception of state power in that the individual was to be taken as an object to be freed from the interventions of the state, neo-liberalism has come to represent a positive conception of the state’s role in creating the appropriate market by providing the conditions, laws and institutions necessary for its operation. . . In the classical model the theoretical aim of the state was to limit and minimize its role based on postulates which included universal egoism (the self-interested individual); invisible hand theory which dictated that the interests of the individual were also the interests of the society as a whole; and the political maxim of laissez-faire. (p. 340). The role of the state, then, has shifted from the classical liberal conception where private and public domains are distinct, to a social democratic notion of liberalism that conceptualized the state as service provider, and now, to the latest iteration where the state is an enabler of the market. Neo-liberalism emerged from the Chicago School, promoted by economists like Milton Friedman and Frederick von Hayek, and later globalized by transnational institutions such as the World Bank, the OECD, and APEC. Key aspects of neoliberalism included: Deregulation of business to free the market of bureaucratic fetters; competition policies across public and private sectors aimed at efficiency; privatization of activities formerly managed by the state; and a process of decentralization coupled with recentralization (Robertson, 2011). Education is a key public sector institution in the neoliberal worldview because of its importance in developing workers and consumers 4 suitable for globalized competition and the new knowledge-based economy. Markets and competition are, in the neo-liberal mindset, appropriately applied to education (Ball, 2007). According to Ball (1998), two complexly related policy agendas are evident in the restructuring of public education systems: The first aims to tie education more closely to national economic interests, while the second involves a decoupling of education from direct state control. The first rests on a clear articulation and assertion by the state of its requirements of education, while the second gives at least the appearance of greater autonomy to educational institutions in the delivery of those requirements. The first involves a reaffirmation of the state functions of education as a public good, while the second subjects education to the disciplines of the market and the methods and values of business and redefines it as a competitive private good. (p.125). Commodification is the result of these two paradoxical policy agendas that are achieved through both decentralization and recentralization. As Karlsen (2000) contends: Decentralization was perceived more and more as a governance strategy for achieving rationalization and efficiency. The argument was that local authorities and the individual schools had the competence needed to use existing funding in a more flexible and efficient way and even obtain new local resources. Decentralization was understood in a more market-oriented way and the argument was that schools should be more like the market system. Therefore, independence and local autonomy should give schools the same opportunity as other businesses to compete in the marketplace. Decentralization was characterized as a strategy for a 5 more privatized and commercialized school (p. 528) Neo-liberalism, then, uses the processes of decentralization/recentralization to make it appear as if commodification and privatization are the result of local initiatives. Transnational institutions and state governments are encouraging privatization of education in insidious ways. Robertson (2011), for example, describes how the World Bank’s Education Strategy 2020, “redefines the meaning of an education system to now include, and enclose the private sector (for profit/not for profit) as key actors within, as opposed to outside, the education system” (p. 14, emphasis included). In BC, the private sector operates outside of public education in the form of privately funded independent schools. Private schools have existed in BC since the mid1800s, before the province joined Canadian Confederation and they continue to exist today. All are tuition-driven schools, some of which cater to elite groups while others focus on career preparation and language acquisition (e.g., business schools; French and English language acquisition). A middle category of schools operates both outside and within public education. Beginning in 1977, the province partially funds schools that qualify by offering the B.C. curriculum. These schools are divided into two categories: Group 1 schools receive 50 percent of the operating grant received by local public boards from the province on a per FTE student basis; Group 2 schools receive per-student operating grants at the 35 percent level, because the school’s per-student operating costs exceed the ministry grants paid to the local boards of education. As of 2011, there were 249 Group 1 schools and 67 Group 2 schools. In addition, 14 Distributed Learning Schools were operating in the province (12 in Group 1; 2 in Group 2) (Ministry of Education, 2011). 6 The Ministry of Education justifies this public support of private schools as follows: “To educate the 72,014 independent school students in the public system would cost $564 million in operating grants to public school districts (based on the average 2010/11 school district per student operating grant of $7,833) plus capital costs. This is $306 million more than the total current operating grants allocated to independent schools” (BC Ministry of Education, 2011, p.3). Thus, government is justifying the continuing subsidization of Group 1 and Group 2 schools using the rhetoric of efficiency. The government is spending fewer dollars per capita in these independent schools than they are spending per capita in public schools. Public subsidization of some independent schools creates a quasi-public level within the education system. If tier one comprises fully independent, privately funded schools, and tier two (the quasi-public education system) comprises independent schools that are partially funded by public grants, then one would expect tier three to mean schools that receive full public funding. However, a structural funding shortfall and the emerging importance of marketdriven revenue generation have fragmented the public school system such that another tier is developing. The following section of the paper focuses on factors that are driving this fragmentation of what was formerly a fully publicly funded school system. First, we discuss the development of a structural funding shortfall in the province; then we examine three aspects of market-driven funding at the local level—school and program choice, enrolment-based public funding, and market-driven private funding. Structural Funding Shortfall The BC Liberal Party (not to be confused with the federal Liberal Party) is a fiscally conservative political party and it has formed the government since 2001. Like 7 other right-of-centre parties before it in BC, particularly the Social Credit government that imposed severe fiscal restraints in the 1980s, the Liberal government places a strong emphasis on fiscal “prudence” and balanced budgets (BC Liberal Party, 2013). One of their first acts upon forming the government in 2001 was to freeze funding for the Ministry of Education (as well as for other government Ministries) and to legislate mandated balanced budgets for school districts across the province. In the 2013 budget, announced on February 19, the BC government has once again virtually frozen education spending for the next three years (Budget and Fiscal Plan 2013/14 - 2015/16). In addition, over the past decade, government’s operating grants to school districts have failed to keep pace with inflation. Meanwhile, school districts have been saddled with new costs resulting from government initiatives, including class size and composition arrangements, carbon tax compliance, and full-day kindergarten, yet the province has not provided additional funding to cover these extra costs (Malcolmson & Kaiser, 2009). As a result of cost increases and budget restraints, school districts have struggled to balance their budgets over the past decade. A survey conducted by Beresford and Fussell (2009) revealed that for the 2008-2009 school year, 32 out of 45 school districts who responded expected operating costs to exceed provincial funding, and more than half of the districts (18) had already used up their reserve funds to balance budgets in previous years. It is now common to hear educators in the province speak about the “underfunding” of education, however Malcolmson and Kaiser (2009) argue that “structural shortfall” is a more appropriate term to describe the reality of education funding in BC. According to these authors: “A structural funding shortfall occurs when 8 revenue lags consistently and chronically behind that which is required to pay for the delivery of publicly-mandated programs and services” (p. 2). We argue that a structural shortfall will, over the long term, coerce school districts into seeking increasing levels of private funding to support core educational programs and services. As we discuss later, differential capacities among school districts to compete for private funding will inevitably lead to inequities in education in the long term. Market or Enrolment-Driven Public Funding/School and Program Choice In 2002, the School Amendment Act (Bill 34) removed the boundaries between school catchment areas within and between districts. As a result, students were no longer restricted to attending their neighbourhood school, and could now attend the school of their choice, provided space was available. At the same time, government revised the funding formula so that public operating grants to local school boards were based almost exclusively on student enrolment. This move made it imperative for school districts to maintain student enrolment numbers in order to retain the same level of public funding; it also provided an incentive to school boards to increase student enrolment as a means of increasing their level of public funding. The policy of open catchment boundaries amounted to the implementation of school choice across the province, while enrolmentdriven public funding policy led school districts to develop unique programs to keep and attract students, amounting to the implementation of program choice. Both school and program choice are now realities across the province and the result has been increased student mobility. In the decade since 2002, students have moved within and across school districts quite readily. Such movement has been more pronounced in urban areas where there are 9 many schools within reach by public transit or by car. In rural areas where distances between schools are far greater, there has been less physical movement of students, but Distributed Learning enables virtual mobility. As an example, the Vancouver School Board reports the following regarding enrolment of secondary students: Our data for secondary schools indicates that approximately 34% of students do not attend their neighbourhood school. These data are consistent on both the east and west side of the city. There is, however, a migration from east to west. With Main Street as the divide, 35% of students on the east side of Vancouver do not attend their neighbourhood school. Of all students in the east, 13.5% choose a school west of Main. For the students east of main, 33% of all students do not attend their neighbourhood school with 3% choosing a school east of Main. Overall, as a district, at the secondary level, this means that we have approximately 8500 students who do not attend their neighbourhood school. (Vancouver School Board, 2012, p. 15) Vancouver’s west side comprises a more affluent population, predominantly middle and upper class professionals of Western European heritage. The east side, in contrast, has a greater proportion of low-income people, with a large percentage of immigrant and refugee families from non-European and non-English speaking cultures. Thus, student mobility within the Vancouver School District demonstrates social class and cultural dimensions. Yoon (2011) conducted a study of school choice (mini schools) within the Vancouver School District (VSD). Mini schools are “small and selective public schools within larger urban public secondary schools” (p. 253). Twenty-seven mini schools exist 10 in the VSD and “what mini schools offer is an upgraded alternative to the standard, comprehensive secondary school curriculum in neighbourhood public schools” (p. 255). In the market for these elite and competitive programs of choice, Yoon describes how west side mini schools in Vancouver are privileged in relation to east side mini schools: “Currently the demand for West side mini schools is so markedly high that the schools can not accommodate all interested families—from across and outside the city—in their auditoriums during information nights. . . . In contrast, East side schools are less popular. Their auditoriums are rarely full during mini school information nights, and they attract students mostly from the East side neighbourhoods” (p. 255). Yoon’s study is evidence of greater capacity to attract students enjoyed by affluent communities of European descent in relation to lower income communities of non-European background. With the advent of Distributed Learning programs (such as E-bus operated by the Nechako School District) students have moved virtually or have opted to take some courses in one school or district while taking Distributed Learning courses from another school or district. According to the BC Ministry of Education (2012), the number of public school students enrolled in Distributed Learning increased from 1.2% to 3.8% between 2001/02 and 2010/11. Since government operational grants are determined by enrolment, Distributed Learning choices impact the level of funding received by the school district. For example, if a secondary student in District A takes some of her or his courses through Distributed Learning in District B, the funding District A receives will be reduced by (and District B’s funding will be increased by) the proportion of the student’s FTE enrolment in District B. Distributed Learning is a manifestation of school and program choice that has racheted up virtual mobility, funding volatility, and competition 11 between school districts. Market-Driven Private Funding Thus far, we have discussed school and program choice as tools for maintaining or increasing levels of public funding within the context of a structural funding shortfall. We now shift to a discussion about a second response to a structural funding shortfall--the generation of private sources of revenue by public schools. In 2002, the BC government amended the School Act (Bill 34), which introduced a unique feature in the K-12 education finance system in BC and in Canada--for-profit “school district business companies (SDBC)”. School boards acquired the legal capacity to incorporate separate private entities to engage in for-profit entrepreneurial activities while protecting their assets from legal and financial liability associated with the SDBC’s business operations. This change devolved part of the authority and responsibility for K12 education finance to the local school board level with the assumption that marketdriven means of resourcing school districts would enhance “the school boards’ ability to generate revenue through other sources and allow them to better meet local educational needs” (British Columbia Hansard Services, 2002, 7(7), p. 3250). With the introduction of the for-profit funding mechanism, the BC government sent a message to school districts that they needed to become more financially selfreliant, and more innovative and adaptive in order to maintain or increase their level of financial resources and flexibility. By enabling school districts to create school district business companies, the government created a competitive arrangement between school districts that they hoped would serve as an incentive to improve their fiscal situation by being responsive to various local, provincial, and international communities of 12 educational consumers. By promoting financial self-reliance, the BC government reframed its role in the K-12 education finance system: From that of exclusive provider of funding to that of enabler responsible for providing opportunities to school districts to compete for both public and private funds. The motive was to limit the cost of education for the government. In 2002, 15 school districts chose to create school district business companies to engage in private-sector activities such as opening and operating BC accredited schools overseas, marketing curricula and software, or providing online educational services to foreign students (Bell, 2006; Steffenhagen, 2010). Several school districts in BC experienced challenges, including cost over-runs as they struggled to develop their capacity to act efficiently in a free market environment, and by 2010 only eight SDBCs were still operating. Most school districts have concentrated on low risk entrepreneurial initiatives, such as establishing tuition generating international student programs, selling advertising space on school property, renting space, selling course materials for onlineeducation, or providing educational or administrative consulting services. As a result of the introduction of market-driven finance, funds generated through private sources increased from $156 million to $190 million (expressed in Canadian dollars) between 2002 and 2012. During the fiscal year of 2011-12, private sources counted for approximately 2.7% of total operating budgets in BC. Equity Implications of Market-Driven Funding Table 1 shows the level of school-generated funding (including international student tuition fees) for all 60 school districts in BC for 2002-03, 2007-08, and 2011-12. School-generated funds include: 13 Revenues from vending machines, cafeterias, field trips, yearbook sales, school fees, graduation fees and band fees. All other funds collected at the school level including those donated for school use by a Parents' Advisory Council (PAC). Market-driven private revenues, including international student tuition and profits from school business district companies (SDBCs). Because all of the funds listed above come from non-government sources we will refer to them as private sources of funding. While data is available to enable us to determine how much of total private funding per district is generated by international student tuition, we are unable to disaggregate further. Private funding proves to be volatile because of unpredictable events (e.g., global recessions; contagious disease epidemics; global conflicts) and variation in global competition. As a general rule, the operation of SDBCs has proven to be less profitable and riskier than other means of generating private funding. “When Rocky Mountain district closed its company, it forgave a $265,000 loan. New Westminster and Surrey districts have yet to collect on loans worth close to $1 million and $100,000 respectively. Langley district lost $166,246 when it folded its company last year” (Steffenhagen, 2010). International student tuition has been the most lucrative source of private funding for school districts. For example, in 2011-12, West Vancouver received $9.8 million in private funding, of which 87% came from international student tuition. In the same year, Vancouver’s private-source revenue amounted to $23.3 million, of which 61% was derived from international student tuition. Both are urban school districts located in the 14 Greater Vancouver Metropolitan area. Even for a few small districts, international student tuition generated over 60% of private revenue from international students in 2011-12: 62% for Gulf Islands (1671 students); and 86% for Vernon (8497 students). Table 1(see appendix 1) reveals that the amount of funding generated from private sources varies substantially between school districts (0.07% - 15.6% of total operating budgets for 2011-12). With the exception of West Vancouver, no other district in the province generated more than 7.9% of its total operating budget in 2011-12 from private sources. Among the 60 school districts in the province, 17 (28%) generated more than 4% of their total operating budgets from private sources in the 2011-12 school year; and 12 (20%) generated no income at all from international students. The latter group comprises some of the smallest and/or most geographically remote districts. Even among the larger, urban districts, the level of locally generated non-governmental funds varies from district to district. For example, in 2011-12 Surrey district (with the highest student enrolment in the province) earned $8.1 million in international student tuition, while Vancouver district (with 10,000 fewer students) earned $14.1 million. The data reveal that the variation in the level of private funding generated is linked to the relative size and geographical location of school districts, and to intersections between these two characteristics. Table 2 (see appendix 2), in part, compares levels of funding generated across school districts in relation to socio-economic information—average before tax household income, according to 2006 census data; and indicators of cultural diversity—size of the Aboriginal population, and size of the English Language Learners population. This table compares nine school districts, organized into three categories reflecting equivalent 15 student enrolment; thus, we have endeavored to compare levels of private funding across school districts of equivalent size. Two additional patterns emerge from an analysis of these data. First, the most affluent school district in the province, West Vancouver (average household income $114,121 in 2006), consistently generated the highest level of private funding from 2002-2012 (15.6% of total operating revenue or $1472 per student). In contrast, the North Okanagan Shuswap, which is equivalent to West Vancouver in terms of numbers of students enrolled, is far less affluent (average household income $22,000 $66,260 in 2006) and generated private funding at a level near the bottom of the scale (0.18% of total operating revenue or $30.67 per student). Based on the nine school districts we compared in Table 2, there appears to be a hierarchical pattern based on socio-economic status, in which the more affluent school districts generate higher levels of private funding. We need to conduct an analysis of a larger number of districts to confirm whether or not this pattern persists across the province. Second, a distinct cultural pattern emerges within these data. Those districts with larger Aboriginal student populations generate lower levels of private funding compared to districts with smaller Aboriginal student populations. As per Table 2, North Okanagan Shuswap, Prince George, and Vancouver Island North (15%, 26%, and 38% Aboriginal enrolment respectively) generate far lower levels of private funding per student ($31, $45, and $32 respectively) compared to West Vancouver, Maple Ridge, and Gulf Islands (0.7%, 7.8%, and 7.7% Aboriginal enrolment respectively) that generate higher levels of private funding per student ($1472, $704, and $576 respectively). 16 Cultural heritage intersects with socio-economic status to exacerbate the differences between school districts. According to Table 2, districts with higher Aboriginal student populations also have lower household incomes. These data reflect a pan-Canadian pattern: Aboriginal communities tend to live on federal reservations, earn lower incomes, and experience higher unemployment in relation to non-Aboriginal communities (Center for Social Justice, 2013). The patterns identified previously reflect inequities across school districts in terms of the level of private funding they generate. However, the inequities we have uncovered go beyond the mere fact that some districts tend to generate more private funding than do others; they reflect structural differences. We argue that the differences reflect variations in capacity to generate private funding. More affluent districts have greater capacity to generate higher levels of funds through donations from parents, community members, and local businesses. Metropolitan districts or districts within close proximity to popular cultural or recreational facilities (e.g., ski resorts, museums, international film festivals) may have greater capacity to attract international students. Local conditions influence district capacity to generate private revenue. As we have discussed above, differences in local conditions relate to things such as size, geographical location, affluence, cultural composition of the school district, and proximity of cultural and recreational amenities that not only exist separately but also intersect in complex ways. These are characteristics that are difficult, and in some cases (such as geographical location) impossible, to change. This means that differential capacities to generate private revenue lead to funding inequities that are endemic and are likely to persist in the long term. 17 Furthermore, such funding inequities across districts correspond to inequitable access to educational program choice in the province of BC. As Table 2 indicates, districts that generate lower levels of private funding also provide a smaller number and variety of programs of choice for district students. For example, North Okanagan Shuswap and Okanagan Skaha districts generate lower levels of private funding and provide fewer programs of choice in comparison to West Vancouver, which is equivalent in terms of student enrolment numbers (6200-6700 students). Similar patterns are found across the three enrolment size categories: The more private revenue per student school districts are able to generate, the larger the number and the greater the variety of educational programs over and above core programming. Additional revenue generated from private funding correlates positively with the number and variety of above-the-core programs available. These data do not necessarily suggest a cause-effect relationship, however, market-driven private funding and market-driven public funding are interdependent. Districts that have greater capacity to generate market-driven private funding also provide more programs of choice. The provision of educational programs above and beyond the core curriculum enable school districts to attract greater numbers of students; and because public funding is enrolment-driven, districts that can offer more programs of choice can also generate increased levels of public funding. This interdependence between public and private aspects of market-driven funding exacerbates inter-district inequities. Discussion Tier Three Privatization 18 Inequities in funding and program offerings within the public school system contribute to the development of a three-tier education system in BC. Tier 1 consists of those schools that are fully funded by private sources. Tier 2 consists of those independent schools that receive a mixture of private and public funding in ratios ranging from 50:50 for Group 1 schools and 65:35 for Group 2 schools. These schools were originally fully private schools before 1977 when government began to subsidize them. Hence, we use the term quasi-public to denote that they have moved along a continuum from the private toward the public, in financial terms. Tier 3 constitutes public school districts that are becoming quasi-private, since they are becoming partially funded by private sources. Public school districts are privatizing themselves, albeit in response to conditions establish by government; so although government is not directly mandating privatization, government is indirectly responsible for this trend. The term quasi-private signifies that these school districts are moving along the private-public continuum toward privatization, in financial terms. Tier 3 privatization is manifested in two forms. The first is related to the dynamics of market-driven private funding. A monetary valuation is directly attributable to this privatization—the services and programs are offered at a price and for a profit. We refer to this as profit-oriented privatization. The second form of privatization stems from market-driven public funding and is connected to programs of choice. These programs are designed to increase public funding for the district through an increase in enrolment. Although the generation of revenue is the catalyst for districts to offer not-for-profit programs of choice, there is a low price or no price to the student. Their value to the student/parent ‘consumer’ is primarily symbolic; thus, we refer to this as symbolic 19 privatization. Market-driven finance is leading to the development of both profit-oriented and symbolic privatization. Programs of choice contribute to the school district’s movement along the continuum from the public toward the private, but in symbolic terms. School districts with the most powerful symbols win in the educational market (Gerwirtz, Ball & Bowe, 1995), so districts with the most valued cultural capital in the eyes of choice-conscious parents are the most successful in the educational marketplace, leaving those districts whose cultural capital is less valued with far less market power. Robertson (2000) argues that competition could lead school districts and schools to act more and more as entrepreneurial accumulating units rather than as institutions with social interests and responsibilities (Robertson, 2000). School districts in BC are at different places along the privatization continuum. Some school districts, like West Vancouver, receive a greater share of their total operating budgets from private sources or programs of choice and therefore, have moved further toward privatization than have other districts, in financial and symbolic terms. Some districts receive virtually nil in terms of private source funding and offer few, if any, programs of choice, and they can be perceived as not having moved at all. The Social Justice Implications of Funding Inequities Market-driven private funding may help a minority of school districts to address the structural funding shortfall in public grants, but the majority lacks the capacity to achieve this and will likely continue to suffer from budget shortfalls; therefore, marketdriven funding reinforces structural inequalities among school districts. These inequities run counter to the traditional values of the provincial education finance system, which has 20 built-in equalization mechanisms to address local realities such as geographical dispersion and unique student needs. Inter-district inequities are quite pronounced and this is worrisome, not because of the relative ability or inability to privatize (indeed, we question whether privatization, in itself, is ethical or just), but because of the implications for accessing quality education and enhancing social mobility. Some districts offer many programs beyond the core, while others offer few or none. Inequities mean more than differential opportunities to access education; they also perpetuate structural social injustices associated with socio-economic and cultural differences, and colonialism. As we have demonstrated previously, market-driven funding reproduces hierarchies along socio-economic and cultural lines. Because communities with significant Aboriginal populations tend to be disadvantaged in terms of accessing higher levels of funding and programs of choice, colonial marginalization of Aboriginal communities is reinforced or goes unchallenged. As Yoon (2011) shows in her study of mini schools in Vancouver, programs of choice are elite and competitive programs that imbue students with cultural capital that facilitates their participation in the globalized employment and advanced education markets. Districts that lack capacity to offer such programs may disadvantage their students. These dynamics reproduce hierarchies of social privilege and marginalization and fail to question structural injustices. The issue of adequacy needs to be addressed, not only in financial, but also in educational and symbolic terms. Market-driven funding may diminish or eliminate local district budget crises, however not all districts have the capacity to accomplish this; 21 therefore, the province-wide structural shortfall remains and perpetuates educational inequities. As long as these exist, school districts will be compelled to compete and the dynamics we have described will persist. The negative effects of competition can be mitigated by taking away districts’ legal capacity to engage in market-driven private funding activities and by removing the structural shortfall that coerces districts to compete for public funding. We need to challenge the assumption that market mechanisms are legitimate and appropriate means to solve financial crises in public education. 22 References Ball, S. J. (1998). Big policies/small world: An introduction to international perspective in education policy. Comparative Education, 34(2), 119 - 131. Bell, J. 2006. “Overseas education initiatives not losing money.” Times Colonist, April 11. Retrieved January 7th, 2013, from http://www.canada.com/victoriatimescolonist/news/capital_van_isl/story.html?id= 955a214d-aba6-45fa-bac2-d2829dcb61fb British Columbia Hansard Services. (2002). Official report of debates of the Legislative Assembly, 3rd session, 37th Parliament. Hansard, 7(12), 3377-3424. BC Liberal Party, 2012. Today’s BC Liberals. What we believe. Retrieved February 12, 2013, from: http://www.bcliberals.com/our_party/what_we_believe/party_principles. BC Ministry of Education. (2011). Overview of independent schools in British Columbia. Victoria, B.C.: Province of British Columbia. http://www.bced.gov.bc.ca/independentschools/geninfo.pdf BC Ministry of Education. (2012). Provincial Reports. 2010/11 Summary of Key Information. http://www.bced.gov.bc.ca/reporting/docs/SoK_2011.pdf. BC Ministry of Finance, (2013). Budget and Fiscal Plan 2013/14 -2015/16. Retrieved February 22, 2013, from: http://www.bcbudget.gov.bc.ca/2013/bfp/2013_Budget_Fiscal_Plan.pdf 23 Beresford, C., and Fussell, H. 2009. When More is Less: Education Funding in BC. Centre for Civic Governance. Retrieved January 7th, 2013, from http://www.columbiainstitute.ca/sites/default/files/resources/WhenMoreisLess.pdf Centre for Social Justice, (2013). Struggling to Escape a Legacy of Oppression. Retrieved February 28, 2013 from: http://www.socialjustice.org/index.php?page=aboriginal-issues. Federation of Independent Schools Association. (2012). Enrolment comparing public and independent-Historical. Retrieved February 20, 2013, from http://www.fisabc.ca/sites/default/files/Enrolment%20Ind%20Public%20Compari son%20%202012.pdf. Gerwirtz, S., Ball, S., & Bowe, R. (1995). Markets, choice and equity. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press. Karlsen, G. 2000. Decentralized Centralism: Framework for a Better Understanding of Governance in the Field of Education, Journal of Education Policy, 15(5), 525538. Malcolmson, J., and Kaiser, J. 2009. Death by a Thousand Downloads . . . A Structural Funding Shortfall for BC Schools. Canadian Union of Public Employees. Olssen, M. (1996). In defence of the welfare state and publicly provided education. Journal of Education Policy, 11, 337 - 362. Rizvi, F. (2008) Rethinking educational aims in an era of globalization. In P. D. Hershock, et al. (Eds.), Changing education—leadership, innovation and development in a globalizing Asia Pacific, 63-91. Comparative Educational Research Centre. 24 Robertson, S. L. (2000). A class act: Changing teachers' work, globalization and the state. New York, NY: Falmer Press. Robertson, S.L. (2011) The Strange Non-Death of Neoliberal Privatisation in the World Bank’s Education Strategy 2020. Centre for Globalisation, Education and Societies, Bristol, UK: University of Bristol. http://susanleerobertson.com/publications/ Steffenhagen, J. 2010. “School District Business Companies – Fading to Red” Vancouver Sun, May 7th. Retrieved January 12, 2013, 2012, from: http://blogs.vancouversun.com/2010/05/07/school-district-business-companiesfading-to-red/. Vancouver School Board. 2012. Vancouver School Board Sectoral Review: Our schools, our programs, our future. Vancouver: Author. Yoon, Ee-Seul. (2011). Mini schools: The new global city communities of Vancouver. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 32(2), 253-268. 25 Appendix 1 Table 1: School-Generated Funds and Off-Shore Tuition-Fee Revenue as a Percentage of Total Operating Funds, 2002–03/2007-08/2011-12 2 2011-12 Average Across the Three fiscal Years Districts Total local revenue ($) Local PerLocal PerLocal PerAverage Average revenue Student revenue Student revenue Student as % of Per-Student as % of Revenue as % of Revenue Total local as % of Revenue operating Revenue operating Total local operating revenue operating funds funds revenue ($) funds ($) funds 1721.70 9,767,729 15.6% 1472.00 16.9% 1441.63 1 8.6% 761.03 9,888,582 7.9% 643.24 7.9% 661.58 2 652.40 19,950,073 8.3% 676.48 19,374,936 7.2% 616.70 8.03% 648.52 3 564.55 1,163,250 7.5% 783.86 868,224 4.9% 576.50 6.22% 641.64 4 7,441,565 6.0% 525.50 9,832,296 7.6% 703.82 6.41% 581.13 5 3,498,231 6.36% 526.68 3,554,421 6.14% 512.75 5.05% 567.05 6 45 West Vancouver 7,404,010 16.57% 44 North Vancouver 9,048,470 7.20% 580.46 12,142,943 43 Coquitlam 17,989,892 8.61% 6.26% 64 Gulf Islands 998,104 Ranking 2007-08 2002–03 1131.20 10,461,073 18.5% 42 Maple Ridge-Pitt Meadows 5,564,278 5.63% 514.08 40 New Westminster 3,905,398 9.02% 661.73 48 Howe Sound 1,708,794 5.13% 368.89 3,084,254 8.7% 764.94 2,337,011 5.9% 556.03 6.57% 556.29 7 35 Langley 10,135,498 7.78% 605.84 9,741,058 6.6% 531.25 7,981,721 5.6% 429.47 6.66% 522.19 8 39 Vancouver 24,709,026 6.12% 520.70 25,471,827 5.6% 462.76 23,314,765 4.8% 416.38 6.4% 466.61 9 5.9% 504.21 10,183,913 5.9% 523.16 5.56% 464.45 10 61 Greater Victoria 7,159,351 4.89% 365.98 9,496,372 2 This table is based on the statistics provided by the Ministry of Education Website under Actual Sources of Other Operating Revenue by School District” (see: http://www.bced.gov.bc.ca/accountability/district/revenue/0809/ and by the BCTF for the year 2002/03 (see: Lowry, M. (2004). Fee-generation as an indicator of developing funding inequities in the B.C. school system available at: http://www.bctf.bc.ca/ResearchReports/2004ef01/report.html 26 22 Vernon 653,558 1.05% 77.03 4,397,553 6.19% 500.00 5,131,282 6.77% 608.98 4.67 395.34 11 37 Delta 6,212,592 5.48% 389.64 5,644,424 4.2% 354.28 6,996,850 4.90% 436.21 4.86% 393.38 12 41 Burnaby 5,319,885 3.45% 276.96 10,558,332 5.5% 447.71 14,438,640 6.8% 445.49 5.25% 389.75 13 63 Saanich 837,573 1.49% 130.16 2,734,001 4.06% 361.35 5,130,474 7.21% 668.29 4.25% 386.60 14 69 Qualicum 1,028,844 2.72% 201.32 2,141,340 4.9% 447.14 2,188,014 5% 508.49 4.20% 385.65 15 38 Richmond 6,203,462 4.01% 352.96 6,151,556 3.5% 279.50 9,886,855 5.3% 452.98 4.27 361.81 16 34 Abbotsford 6,919,013 5.57% 445.03 5,210,543 3.6% 284.73 4,830,420 3.02% 252.88 4.06% 327.55 17 62 Sooke 2,359,740 3.81% 310.77 2,631,410 3.7% 314.24 3,030,813 3.8% 325.89 3.77% 316.97 18 47 Powell River 758,480 3.56% 289.99 848,787 3.8% 354.40 880,247 3.82% 271.10 3.72% 305.16 19 08 Kootenay Lake 793,200 1.68% 135.12 1,588,700 3.16% 321.99 1,740,401 3.33% 339.39 2.72% 265.55 20 75 Mission 955,349 1.99% 156.48 2,326,122 4.2% 341.07 1,504,106 2.73% 248.28 2.73% 248.61 21 06 Rocky Mountain 1,070,174 3.22% 223.30 0.26% 26.05 1,431,306 4.25% 465.01 2.6% 238.12 22 36 Surrey 12,852,676 3.32% 274.06 17,359,082 3.5% 269.00 12,081,513 3.0% 171.71 3.27% 238.26 23 71 Comox Valley 2,090,294 3.23% 223.37 2.5% 209.24 2,335,356 3.1% 278.31 2.95% 236.95 24 87 Stikine 198,315 3.31% 268.57 102,138 1.54% 383.97 6,484 0.1% 32.74 1.65% 228.42 25 59 Peace River 1,046,036 South 2.60% 198.51 1,463,054 3.3% 338.43 582,358 1.3% 143.83 2.41% 226.92 26 84 Vancouver Island West 68,170 1.07% 87.64 119,685 1.82% 272.63 126,544 1.57% 285.65 1.48% 215.30 27 68 NanaimoLadysmith 1,927,887 1.82% 144.38 3,578,019 3.0% 249.25 3,241,569 2.6% 240.78 2.47% 211.47 28 05 Southeast Kootenay 323,677 0.69% 54.23 1,253,534 2.55% 235.18 1,630,959 3.11% 304.96 2.12% 198.12 29 74 Gold Trail 608,767 2.89% 210.77 444,486 2.07% 293.39 48,635 0.28% 37.81 1.74% 180.65 30 82,489 1,782,743 81 Fort Nelson 80,194 0.86% 66.23 190,720 1.85% 195.40 207,459 2.04% 241.51 1.58% 167.71 31 19 Revelstoke 155,388 1.49% 128.64 145,542 1.42% 128.91 221,845 2.16% 217.29 1.69% 158.28 32 28 Quesnel 370,899 1.08% 89.15 676,272 1.84% 170.00 713,578 1.94% 199.49 1.62% 152.88 33 27 79 Cowichan Valley 1,322,642 1.96% 149.79 1,011,883 1.41% 115.80 1,427,391 1.95% 175.16 1.77% 146.92 34 50 Haida Gwaii/Queen Charlotte 132,131 1.37% 122.43 18,889 0.18% 25.42 187,455 1.8% 289.73 1.11% 145.86 35 33 Chilliwack 2,466,467 3.09% 221.25 825,521 0.86% 68.52 1,892,275 1.7% 141.91 1.88% 143.89 36 49 Central Coast 15,676 0.34% 63,443 1.19% 233.24 36,838 0.60% 159.47 0.60% 141.24 37 92 Nisga’a 347,148 4.43% 359.00 21,695 0.25% 49.30 5,843 0.07% 13.01 1.58% 140.44 38 60 Peace River 174,665 North 0.41% 37.03 747,524 1.47% 132.61 1,405,227 2.55% 248.75 1.47% 139.46 39 93 Conseil scolaire francophone 463,810 1.37% 115.82 756,900 1.15% 190.51 277,071 0.42% 60.13 0.98% 122.15 40 73 KamloopsThompson 1,022,636 0.91% 71.12 1,941,973 1.65% 137.77 1,469,623 1.18% 103.71 1.24% 104.20 41 23 Central Okanagan 1,384,075 1.01% 72.10 1,275,810 0.78% 61.24 3,725,670 2.5% 168.73 2.5% 100.74 42 72 Campbell River 434,879 0.90% 69.42 802,039 1.55% 138.00 479,991 0.94% 90.17 1.13% 99.19 43 82 Coast Mountains 901,156 1.76% 138.90 247,032 0.47% 46.44 514,353 0.96% 101.27 1.06% 95.54 44 10 Arrow Lakes 48,324 0.67% 53.83 72,386 0.97% 121.24 53,300 0.74% 104.92 0.79% 93.33 45 57 Prince George 1,677,648 1.35% 114.12 1,793,856 1.4% 120.32 608,608 0.47% 45.14 1.07% 93.19 46 53 Okanagan Similmakeen 364,738 1.60% 133.90 235,972 0.86% 86.34 144,000 0.58% 58.18 1.01% 92.80 47 70 Alberni 331,313 0.89% 69.18 484,983 1.27% 114.35 341,810 0.86% 80.63 1.00% 88.05 48 52 Prince Rupert 327,039 1.28% 105.82 105,469 0.38% 41.52 236,603 0.86% 107.20 0.84% 84.84 49 78 Fraser Cascade 147,562 0.81% 64.31 358,864 1.83% 174.12 21,166 0.10% 11.88 0.91% 83.40 50 31.01 28 67 Okanagan Skaha 516,279 1.04% 72.13 578,469 1.02% 85.69 526,759 0.90% 84.20 0.90% 80.67 51 91 Nechako Lakes 307,325 0.71% 59.30 355,526 0.71% 70.69 350,518 0.65% 69.59 0.69% 66.52 52 20 KootenayColumbia 330,621 0.86% 68.48 293,867 0.79% 68.59 203,016 0.54% 51.33 0.73% 62.80 53 51 Boundary 142,177 0.91% 69.42 101,066 0.60% 66.01 67,678 0.41% 50.28 0.64% 61.90 54 132,095 0.34% 37.36 120,872 0.34% 37.22 0.62% 56.68 55 318,031 0.60% 54.32 200,039 0.36% 37.42 0.57% 51.94 56 158,334 0.61% 64.23 49,516 0.19% 19.95 0.19% 51.81 57 41,013 0.18% 16.29 77,933 0.32% 34.07 0.44% 38.60 58 37,425 0.20% 22.80 39,273 0.20% 26.18 0.29% 32.60 46 Sunshine Coast 364,914 1.17% 95.46 27 Cariboo Chilcotin 407,042 0.76% 64.10 58 Nicola Similkameen 207,013 0.93% 71.27 54 Bulkley Valley 173,010 0.82% 65.44 85 Vancouver Island North 97,988 0.49% 48.82 83 North OkanaganShuswap 288,682 0.50% 51.13 Totals $155,853,954 3.82% 59 169,151 0.27 270.75 186,830,394 3.40% 23.59 116,107 0.18% 273.37 190,068,241 2.87% 17.31 0.31% 30.67 266.91 2.87% 253.83 60 29 Appendix 2 Table 2 School Districts West Vancouver School District # 45 Group 1 2011/2012 Per-Student Revenue from SchoolGenerated Funds and Off-Shore Tuition-Fee 6728 $1,472.00 The West Vancouver School District is an urban district located in Metropolitan Vancouver. 9.8% of the student population are English Language Learners while 0.7% are Aboriginal students. The average household income before tax is $114,121.00 (Statistics Canada, 2006) Okanagan Skaha School District # The School District is located in the Okanagan Valley in the interior of British Columbia around the towns of Penticton and Summerland. 1.6% of its student population are English Language Learners while 11.7% are Aboriginal students. The average household income before tax is $71,000 in Penticton and $62,126 in Summerland (Statistics Canada, 2006). Okanagan Shuswap School District 2011/12 School‐Age Funded FTE Enrolment North Okanagan-Shuswap School District is located in a rural area around Shuswap 1.7% of its student population are English Language Learners while 15% are Aboriginal students. The average household income before tax is between $22,000 (Sicamous) to $66,260.00 in Salmon Arms (Statistics Canada, 6208 $84.20 Description of programs of choice offered in each school district Primary and Elementary Programs French Immersion (Early) French Immersion (Late) IDEC (Inquiry-based Digitally Enhanced Community) Program (Caulfeild Elementary) International Baccalaureate Primary Years Programme Montessori Program Secondary Programs ACE-IT (Accelerated Credit Enrolment to Industry Training) Advanced Placement French Immersion (Secondary) International Baccalaureate Diploma Programme International Baccalaureate Middle Years Programme International Student Programs Super Achievers Sports Academies Baseball Academy Hockey Academy Soccer Academy Tennis Academy Primary and Elementary Programs Gifted program - one session per week Secondary Programs Late French Immersion (For Grades 6 – 12) 6451 $ 30.67 Advanced Placement (AP) is a program of university level courses and examinations for high school students. Okanagan Hockey Academy International Student Programs Primary and Elementary Programs Early French Immersion Late French Immersion (Grades 6 – 7) Gifted Program (Grade 3 to 7) Secondary Programs Late French Immersion International Student Programs 30 2006). School Districts Maple-Ridge School District Group 2 2011/2012 Per-Student Revenue from SchoolGenerated Funds and Off-Shore Tuition-Fee $703.82 13540 $240.78 Maple-Ridge School District is located in the urban areas of Maple Ridge and Pitt Meadows in the rural area of the Fraser Valley. 2.1% of its student population are English Language Learners while 7.8% are Aboriginal students. The average household income before tax is between $$84,799.00 (Pitts Meadow) and $89,112.00 (Maple Ridge) (Statistics Canada, 2006). Nanaimo-Ladysmith School District 2011/12 School‐Age Funded FTE Enrolment 14123 The Nanaimo-Ladysmith School District is a urban district located in mid-Vancouver Island. 4.2% of its student population are English Language Learners while 16% are Aboriginal students. The average household income before tax is $57,841.00 (Statistics Canada, 2006). Prince George School District Prince George School District is situated where the Nechako River joins the Fraser River near the center of British Columbia. 9.3% of its student population are English Language Learners while 26.3% are Aboriginal students. The average household income before tax is $88,494.00 (Statistics Canada, 2006). 13225 $45.14 Description of programs of choice offered in each school district Primary and Elementary Programs French Immersion (Early) Montessori Program One-to-One Laptop Program (Grades 6/7) K-7 Environmental School Project Literacy: iPod Program (Grades 3/4) Odyssey - Self-Directed Learning Community (Grades K-7) Secondary Programs ACE-IT (Accelerated Credit Enrolment to Industry Training) French Immersion (Secondary) International Baccalaureate Diploma Programme International Student Programs Academies Equestrian Academy Digital Arts Academy Hairdressing Academy Hockey Academy Soccer Academy Interdisciplinary Arts Academy Primary and Elementary Programs French Immersion (Early) Secondary Programs Career Technical Centre (Grades 11/12) French Immersion (Secondary) International Student Programs Academies Jazz Academy Performing Arts Academy Hockey Canada Skills Academy Pacific Soccer Academy I Primary and Elementary Programs French Immersion (Early) Traditional Program Montessori Secondary Programs Career Technical Centre (Grades 11/12) French Immersion (Secondary) International Student Programs 31 School Districts 2011/12 School‐Age Funded FTE Enrolment 2011/2012 Per-Student Revenue from SchoolGenerated Funds and Off-Shore Tuition-Fee 1671 $576.50 1787 $83.40 1475 $32.20 Description of programs of choice offered in each school district Gulf Island School District The Gulf Islands School District is located on seven major islands situated in the Georgia Strait, between the BC mainland and the east coast of Vancouver Island. 1.2% of its student population are English Language Learners while 7.7% are Aboriginal students. The average household income before tax is $54,840.00 (Statistics Canada, 2006). Fraser Cascade School District Group 3 Fraser-Cascade School District is located in the Eastern Fraser Valley of British Columbia 3.7% of its student population are English Language Learners while 35.4% are Aboriginal students. The average household income before tax is $22,870.00 (Statistics Canada, 2006). . Vancouver Island North School District Primary and Elementary Programs French Immersion (Early) Secondary Programs Career Technical Centre - Secondary ApprenticeshipProgram (Grades 11/12) French Immersion (Secondary) International Student Programs Academies Gulf Islands School of Performing Arts (GISPA) Gulf Islands Centre for Ecological Learning (GICEL) Saturna Ecological Education Centre (SEEC) Secondary Programs Fraser-Cascade Mountain School Program International Student Programs No choice or International Student Programs Vancouver Island North School District is located on the northern tip of Vancouver Island which includes the town of Port Hardy, Port McNeill and Woss as well as the adjacent smaller islands such as Alert Bay. 9.1% of its student population are English Language Learners while 38.2% are Aboriginal students. The average household income before tax is between $25,123.00 in Alert Bay and $72,445.00 in Port Hardy (Statistics Canada, 2006). Data excerpted from Table 1b Provincial Overview of Funded FTE Enrolment (Full-Year), 2011/12: http://www.bced.gov.bc.ca/k12funding/funding/11-12/operating-grant-tables.pdf. Statistic Canada, 2006. Profile for Canada, Provinces, Territories, Census Divisions and Census Subdivisions, 2006 Census: http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2006/dp-pd/prof/rel/Rpeng.cfm?TABID=1&LANG=E&APATH=3&DETAIL=0&DIM=0&FL=A&FREE=0&GC=0&GK=0&GRP=1&PID= 94533&PRID=0&PTYPE=89103&S=0&SHOWALL=0&SUB=0&Temporal=2006&THEME=81&VID=0&VNAME E=&VNAMEF= 32