Brooklyn Bridge papaer

advertisement

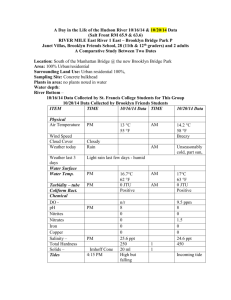

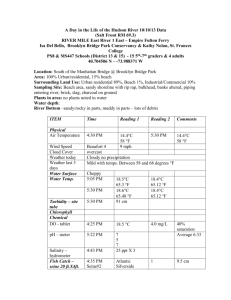

Canning To what extent was the 1898 merger, creating the “Greater New York,” a result of the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge, physically uniting the boroughs of Brooklyn and New York across the East River? Gabrielle Canning UNIV 112 Due December 5, 2014 Word Count: 2,275 1 Canning The two towering structures stretching across the East River in New York have been regarded, through the years, not only as an iconic American landmark, but a factor that greatly impacted the history of New York City. Concerning the impact of the Brooklyn Bridge, this investigation will consider the impact of the bridge’s construction in regards to the unification of the Greater New York in 1898. In more relative terms, this research is focused on how the great bridge may have affected the merger strictly between the two separate cities of New York and Brooklyn. Though some consideration will be shown to the multiple factors that led to the consolidation of Brooklyn and New York, the greater extent of the paper will serve to highlight the vital role of the Brooklyn Bridge being constructed across the East River, which, therefore, affected the consolidation process. Such arguments will be supported by the analysis done by historians, and how they perceive the impact of the Brooklyn Bridge’s construction. It therefore becomes evident that although New York City had looked to expand its borders as early as 1830, the physical unification of New York and Brooklyn brought on by the Brooklyn Bridge, combined with the protracted and strenuous construction era of the Bridge, made consolidation in 1898 inevitable. Historical Context In order to understand the extent at which the Brooklyn Bridge impacted both New York and its surrounding boroughs, it is vital to understand the extremity and cost of the construction process. In the years following the Civil War, a large population of Brooklyn’s locals worked across the East River in the Manhattan workforce. In order to cross the River, workers relied on ferries (the only existing form of transport between the two cities), and during the winter years, the frozen river forced ferries to shut down1. With such inconveniences hindering many individuals’ ability to cross the East River for work, the professional lives of many Brooklynites 1 Robert Silverberg, Bridges (Philidelphia: Macrae Company, 1996), 79. 2 Canning were jeopardized. In order to combat these circumstances, political leaders in the city of Brooklyn requested a bridge be built, and in the middle of the 19th century the New York Bridge Company was organized to connect to borough to Manhattan2. The decision to construct a bridge between Brooklyn and Manhattan is what many historians look to as the point when consolidation became inevitable. By allowing a physical unification between two cities (whose economies were already very close knit given the large amount of Brooklynites working in Manhattan), the likelihood of classifying the boroughs as separate lessened. During the year of 1857 John Roebling, a German immigrant engineer, addressed the possibility of constructing a suspension bridge from the Brooklyn side of the East River, across to the Lower end of Manhattan—around the City Hall area3. Unfortunately, John Roebling died two weeks after an accident occurred on a ferry while he was taking measurements for the bridge. John Roebling’s death allowed for his oldest son, Washington Roebling, to assume his position4. In order to construct the bridge, caissons were to be installed at the rock bed of the East River in order to support the bridge. The caisson installation process was particularly trying in the East River rock bed, because rather than a soft mud floor, the caissons had to be driven through rocklike clay—this allowed caissons to go town at a measly six inches per week. The Brooklyn caisson was finally able to reach bedrock on May 18725. The builders, however, then faced a greater task of installing the New York side caisson, where the bedrock was located an additional 33 feet deeper than the Brooklyn caisson6. During this period, Washington was forced 2 Robert Silverberg, Bridges, 80. Ken Burns, PBS, Brooklyn Bridge, Part 1. 4 Deborah Nevins, The Great East River Bridge 1883-1983 (New York: Brooklyn Museum, 1983), 3 http://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/research/brooklyn_bridge/pdf/GERB_03_1869-1883-1983.pdf. 5 David McCullough, The Great Bridge, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1972, 85. 6 Ken Burns, PBS, Brooklyn Bridge, Part 1. 3 3 Canning to consider many ethical circumstances, mostly concerning worker safety. The conditions of installing the New York caisson called for men to work at a pressure of 25 pounds per square inch, which put many at the risk of caisson disease7. The labor, therefore, called the construction team to work in unethical conditions where constructing a safe foundation for the bridge came at the cost of many workers’ health. Such an example becomes evident in the case of Washington Roebling, himself, who became crippled with paralysis after working a shift of twelve consecutive hours in the caisson shaft. After the accident, Washington was unable to return to the construction site for the remainder of the Brooklyn Bridge’s construction8. After these events, the unethical conditions of the working conditions became all the more evident, and Roebling was forced to make a bold decision—in 1975 construction of the New York caisson was completed as Roebling made the choice to halt the decent of the New York caisson 30 feet before bedrock9. Roebling, therefore, had to weigh the ethical options of safety by either risking the health and lives of workers, or taking the chance of having a less stable structure. Roebling’s decision goes against the utilitarian ethical framework commonly used in current society and policy, where the good of a small group is often sacrificed for the greater whole. In 1883, the Brooklyn Bridge was finally opened to the public after a construction period of fourteen years, and a cost amounting over thirteen million—a price far greater than the predicted value due to the cable fraud situation in 1877-1880 leading the arrest of J Lloyd Haigh who was convicted of fraud for supplying faulty wires that did not meet inspection10. The completion of the bridge led to the influx hundreds of immigrants residing in Manhattan into the 7 8 9 10 Ibid. Ibid. Ibid. Robert Silverberg, Bridges, 80. 4 Canning suburbs of Brooklyn in order to escape the high rent fees of small apartments in New York11. As the borough of Brooklyn began to accommodate the large masses of Manhattan residents wishing to escape to the more suburban scope of Brooklyn, the bridge soon became a center of constant transport between the two cities, strengthening both their economic and physical ties12. Historians, therefore, consider his increased exchange and traffic between the two cities as the final condition, which finalized the inevitability of unification. Analysis Until the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge, ferries were the only form of connection between the two cities of New York and Brooklyn, and were often shut down during harsh winters13. Although many believe that the Brooklyn Bridge was built to unite these two cities, historian David McCullough, States that Brooklyn and New York were already married through commerce. Brooklyn Bridge Centennial Commissioner, Ed Cohen, highlights this bond by stating that both Brooklyn and New York were not combined by the consolidation of 1898, but rather had already merged economically, socially, and physically long before the bridge was even in existence14. McCullough argues that the bridge was built because New York was running out of space. He further states, “The Bridge was built not to get into New York, but to get into Brooklyn15.” Though this argument contradicts that which claims that the Bridge was necessary to accommodate the workers who had to commute from Brooklyn into Manhattan, it is important to consider the lack of architectural technology and advancements during the era. At the time, buildings did not span above five stories, and it was not until the steel advancements 11 History of Brooklyn http://www.thirteen .org/Brooklyn/history/history3.html. 12 Ibid. 13 Robert Silberberg, Bridges, 80. 14 Rick Burns, PBS, New York: A Documentary Film, Disc 3. 15 Ibid. 5 Canning brought upon by the bridge’s construction that New York was able to become a “vertical city”16. McCullough’s belief is supported by historian, Deborah Nevins, whose essay featured on the Brooklyn Museum website argues that physical connection between the two cities provided by the bridge allowed for individuals to expand from Manhattan, across the East river, into the suburbs of Brooklyn. In words very similar to McCullough, Nevins remarks that “Brooklyn was not just for Brooklynites,” and that even before the annexation in 1898, many New Yorkers had crossed the bridge and expanded themselves all the way to Cony Island17. In McCullough’s own book, titled the Great Bridge, McCullough states that “the time following the bridge can be seen as the beginning of a modern New York: of monumental scale and steel structure—or the end of old Brooklyn”18. McCullough’s claim, therefore, alludes to a surmise that consolidation occurred, not only in respects to the physical connection provided by the bridge, but the technological growths as well. As architecture and construction technology grew more advanced through the construction of the bridge (the two towers standing as the tallest structures in the city after their completion), the conditions gave rise to a new era where the growth of urban planning would not allow the boroughs to remain separate. Despite the bridge’s physical unification of the two cities, it is important to understand that the advocacy for consolidation had been present long before the construction of John and Washington Roebling’s bridge. Historian George J Lankevich states that the support for New York expansion had been prevalent since the early 1830’s when Andrew Hashweel Green, a lawyer and reformer, strongly advocated for the annexation of New York’s surrounding cities and led the crusade for this movement on his own for thirty years19. However, despite the earlier 16 17 18 19 Rick Burns, PBS, New York: A Documentary Film, Disc 3. Deborah Nevins, The Great East River Bridge 1883-1983, 15. David McCullough, The Great Bridge, 550. George J. Lankevich, New York City: A Short History, (New York: New York University Press, 1998) 132. 6 Canning support for consolidation, Lankevich remarks that during the 1880’s, after the opening of the Brooklyn Bridge, life in Brooklyn’s suburbs became more appealing as an alternative for many upper class New Yorkers20. Therefore, it is apparent that the construction of the Bridge resulted in far greater reasons for unification than Green’s 30-year campaign, and other similar movements. Additionally, Lankevich argues that it wasn’t until the bridge physically connected the two cities that the value of Green’s campaign became apparent—this was because the Brooklyn Bridge “not only provided a convenient passageway to the fields of Brooklyn, but also probably made the creation of Greater New York inevitable”21. Lankevich’s argument is shared by the History Channel’s Modern Marvels, which states that the Brooklyn Bridge was the leading factor to the 1898 “merger” that created the Greater New York22. Historian, Phillip Lopate comes to a similar conclusion, remarking that “the amalgamation had been inevitable ever since the opening of the Brooklyn Bridge in 1883”23. These arguments therefore highlight that though unification had been a highly probable outcome long before the completion of the Brooklyn Bridge, construction of the bridge served to expedite the process of unification, as well as give strength to campaigns such as those of Andrew Hashweel Green. It is therefore justly supported that consolidation would not have occurred at the same speed and extent, had construction of the bridge not occurred at the time it did. Conclusion At the start of the New Year, on January 1, 1898, the city of New York expanded its borders, annexing Brooklyn, the Bronx, and 38 villages in Queens24. Ever since the 1830’s, long before the Bridge began construction, the idea of expanding the boundaries of New York City 20 21 22 23 24 Ibid, 119. Ibid, 120. History Channel, Modern Marvels: Brooklyn Bridge. Phillip Lopate, The Greatest Year: 1898 (New York Magazine, 2011). Rick Burns, New York: A Documentary, Disc 3. 7 Canning had been debated25. In 1889 Andrew Hashweel Green advocated the State Assembly to grant a commission to consider the consolidation of Brooklyn and New York; however, Brooklyn legislators shut down this proposal. Despite this, on May 8, a law creating a study commission for consolidation was granted26. Brooklyn fought to resist annexation until 1898 when it finally gave up its independence to become part of the Greater New York, and governed by Robert Van Wyck27. The consolidation was passed in Brooklyn by a margin of 277 votes, out of more than 129,000 cast28. To this day the Brooklyn Bridge remains an American icon, displaying the effects of the country’s industrialization and innovation, and serving as a template for many suspension bridges following its construction. Roebling’s many ethical challenges allowed for a better understanding of the difficulties of suspension bridge construction and caisson installation, which therefore benefitted the later construction of many other notable American bridges, such as the Golden Gate Bridge in 1933. The new technological advances regarding steel that emerged from the bridge made it possible for New York to grow vertically, allowing for skyscrapers that extended over five stories. Another notable step forward in US history can be reflected by the Bridge’s history—because immigrants, essentially, built the bridge, the bridge epitomizes the diversity of the US industrial era. Although New Yorkers supported consolidation as early as the 1830’s, it was not until after the bridge opened that the formation of a Greater New York seemed inevitable, therefore emphasizing how the Brooklyn Bridge was the main reason why the Greater New York was achieved in 1898. 25 George J Lankevich, New York City: A Short History, 132. Ibid. 27 Ibid. 28 Kenneth T. Jackson and David S. Dunbar, Empire City: New York Through the Centuries (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002), 410. 26 8 Canning Bibliography Brooklyn Bridge. DVD. Directed by Ken Burns. Alexandria, VA: PBS Home Video, 2004. Jackson, Kenneth T., and David S. Dunbar. Empire City: New York through the centuries. New York: Columbia University Press, 2002. Lankevich, George J.. New York City: A Short History. New York: New York University Press, 2002. Lopate, Phillip. “The Greatest Year: 1898.” New York Magazine, January 9, 2011. http://nymag.com/news/features/greatest-new-york/70466 McCullough, David G.. The Great Bridge, New York: Somon and Schuster. 1972. Nevins, Deborah. “The Great East River Bridge, 1889-1983 (New York: Brooklyn Museum).” Brooklyn Museum www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/research/brooklyn_bridge/pdf/GERB_03_18 9-1883-1983.pdf. “Disc 3.” New York: DVD. Directed by Rick Burns. Alexandria, VA.: PBS Video;, 1999. Silverberg, Robert. Bridges. Philadelphia: Macrae Smith, 1966. 9 Canning The Brooklyn Bridge. DVD. Directed by Earl Boen. New York, NY: History Channel, 1995. Disclaimer: Several of the sources, as well as historical context points were used from a previous paper I had written on the topic two years ago. 10