The Life of Catherine McAuley

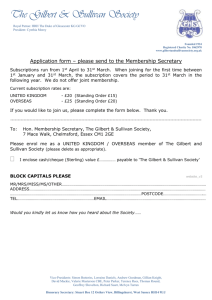

advertisement

Mary C. Sullivan, The Path of Mercy: The Life of Catherine McAuley, Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press, 2012, ISBN 978-1-84682-320-6 (hardcover), pp vii + 419 Reviewed by: Mary Beth Fraser Connolly, Lilly Fellows Program in Humanities and the Arts, Valparaiso University, USA, August 2012 Anyone with an interest in the history of women religious in general and the Sisters of Mercy specifically will be gratified by Mary C. Sullivan’s highly anticipated biography of Catherine McAuley, the foundress of the Sisters of Mercy. This comprehensive work provides a close read of McAuley’s life, from the early years of her childhood, through her founding of the Sisters of Mercy, up to her death in 1841. Over the course of this deep history, Sullivan explores both the spiritual and secular motives of her subject and gives a more complete picture of the life of Catherine McAuley. Many may be familiar with Sullivan’s other books, such as The Correspondence of Catherine McAuley, 1818-1841 (2004), Catherine McAuley and the Tradition of Mercy (2000), and The Friendship of Florence Nightingale and Mary Clare Moore (1999). With such extensive works such as these on Catherine McAuley, the Sisters of Mercy, and even one of the first members of her congregation (Moore), one would not think a biography of Catherine McAuley is needed. Mary C. Sullivan, however, has spent years devoted to researching and writing about the Mercy foundress and the insight and detail which she brings to this new biography brings the reader closer to understanding the spiritual and historical context of McAuley’s life. In particular, one of the largest debates of the founding of the Sisters of Mercy is whether or not McAuley was compelled by the Church to establish a religious congregation in order to continue her benevolent work while living in community with other single women. Sullivan adeptly gives insights into McAuley’s religious and spiritual transformation and her intentional movement toward vowed religious life. This is equally true of Sullivan’s treatment of McAuley’s life as a religious. She founded the Sisters of Mercy in her mid-life, after entering the Presentation Sisters novitiate and reacted against the constrictions of religious life. McAuley, while remaining a devoted Catholic all her life, lived and interacted mainly with Protestants. Sullivan argues that this informed her conception of religious life as she established the Sisters of Mercy. McAuley resisted some of the more restrictive elements of religious life and often counseled the members of her community to avoid too much austerity and to embrace humor. Sullivan also pauses periodically in her narrative to investigate Catherine McAuley’s spiritual motivation at various moments of her development from laywoman to religious founder. Furthermore, Sullivan does not shy away from Catherine McAuley’s missteps as congregational leader, as she details conflicts with local clergy, disputes with family, financial blunders as in the case of business ventures like a laundry, and the starts and stops of new foundations throughout Ireland and England. Often biographies of founders of religious congregations, especially those with a foundress with an active cause for canonization, will include trials and troubles, but only as something which the good sister overcame with the grace of God. Sullivan, admittedly biased and devoted to Catherine McAuley as a member of the Sisters of Mercy, does not fall into this trap. By laying out McAuley’s short-comings as well as her positive qualities, Sullivan provides a rich portrait of the foundress of the Sisters of Mercy. Sullivan offers a rich narrative of Catherine McAuley’s life that provides a more complete picture of the Mercy foundress, who evolved in religious life. The detail which Sullivan brings to her biography results in a more three-dimensional historical actor. Sullivan does not hide from her readers her connection to the Sisters of Mercy or her affection for Catherine McAuley. As a member of this religious congregation, Sullivan has been formed within Mercy spirituality and charism. She writes as an insider, and there is always the risk that a historian’s closeness with a person or institution and its way of thinking colors her perception or interpretation of that institution. Mary Sullivan’s insider-status, however, will bring her readers into the world of Catherine McAuley in a new and more intimate way. The Path of Mercy is a valuable contribution to the historiography of Catherine McAuley, the Sisters of Mercy, and of women religious.