10 Criteria for Good Educational Ethnographies

advertisement

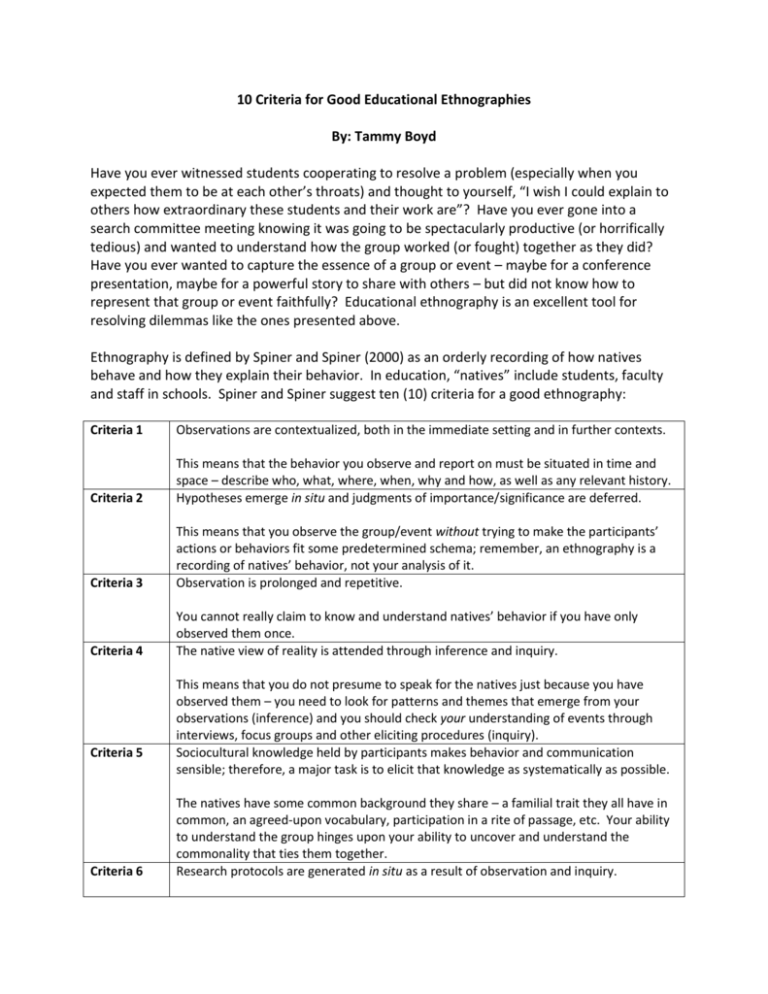

10 Criteria for Good Educational Ethnographies By: Tammy Boyd Have you ever witnessed students cooperating to resolve a problem (especially when you expected them to be at each other’s throats) and thought to yourself, “I wish I could explain to others how extraordinary these students and their work are”? Have you ever gone into a search committee meeting knowing it was going to be spectacularly productive (or horrifically tedious) and wanted to understand how the group worked (or fought) together as they did? Have you ever wanted to capture the essence of a group or event – maybe for a conference presentation, maybe for a powerful story to share with others – but did not know how to represent that group or event faithfully? Educational ethnography is an excellent tool for resolving dilemmas like the ones presented above. Ethnography is defined by Spiner and Spiner (2000) as an orderly recording of how natives behave and how they explain their behavior. In education, “natives” include students, faculty and staff in schools. Spiner and Spiner suggest ten (10) criteria for a good ethnography: Criteria 1 Observations are contextualized, both in the immediate setting and in further contexts. Criteria 2 This means that the behavior you observe and report on must be situated in time and space – describe who, what, where, when, why and how, as well as any relevant history. Hypotheses emerge in situ and judgments of importance/significance are deferred. Criteria 3 This means that you observe the group/event without trying to make the participants’ actions or behaviors fit some predetermined schema; remember, an ethnography is a recording of natives’ behavior, not your analysis of it. Observation is prolonged and repetitive. Criteria 4 You cannot really claim to know and understand natives’ behavior if you have only observed them once. The native view of reality is attended through inference and inquiry. Criteria 5 Criteria 6 This means that you do not presume to speak for the natives just because you have observed them – you need to look for patterns and themes that emerge from your observations (inference) and you should check your understanding of events through interviews, focus groups and other eliciting procedures (inquiry). Sociocultural knowledge held by participants makes behavior and communication sensible; therefore, a major task is to elicit that knowledge as systematically as possible. The natives have some common background they share – a familial trait they all have in common, an agreed-upon vocabulary, participation in a rite of passage, etc. Your ability to understand the group hinges upon your ability to uncover and understand the commonality that ties them together. Research protocols are generated in situ as a result of observation and inquiry. Criteria 7 Criteria 8 Criteria 9 Criteria 10 Nuts and bolts details like scheduling focus group interviews are done after you know the natives’ schedule (and after you know you will not interfere with an important meeting or big test!). Same goes for the questions to be asked during the interview, the coding schema for analyzing the interviews, etc. Cultural variation over time and space is considered a natural human condition. Do not expect a student group founded in the 1950’s to look, sound or act the same today as it did back then. Some sociocultural knowledge is implicit or tacit; a significant task of ethnography is to make the implicit explicit. In addition to recording what the group sees as its defining feature(s) (see Criteria 5), you should also record those actions, words, behaviors, etc. that the group is not aware they engage in. Examples include unconsciously racist, sexist, ageist and/or homophobic behaviors. Since the native is the one who knows the culture, the ethnographer must not predetermine responses by question structure. Do not phrase questions so that you get the answer you want (“Interrupting is rude, don’t you agree?”), phrase questions so that the native can tell you what is the norm for his/her group (“Describe a typical conversation between group members.”) Any technical device that will enable the ethnographer to collect more data should be used. With the natives’ consent, feel free to use camcorders, microcassette recorders, etc. to aid in data collection. Ethnographies are not easy – they are exacting, time-consuming and exhaustive; they require excruciating attention to detail and constant verification of information. But the richness of data they generate and the descriptions of people and events they enable make them well worth the effort. Reference Cited Spiner, G. and Spiner, L. (2000). Fifty years of anthropology and education, 1950-2000: a Spindler anthology. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.