Student Perceptions of Academic Staff

advertisement

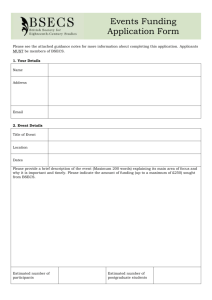

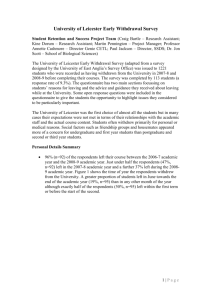

Undergraduate Student Perceptions of Academic Staff This case study focused on the students’ perceptions of academic staff and the possibility that they might believe that the primary role of academic staff is to provide teaching. This misconception can create unrealistic student expectations about the level of support that undergraduate students receive whilst at university, in comparison with support available at secondary school, including the speed of communications and the academics’ role in the student experience. The study also investigated what students are told about the functions of academics during induction across different departments within a UK HE institution. Survey of Academic Heads of Department and the Chairs of Teaching and Learning Committees As a preliminary to the main study, all academic heads of department and the chairs of teaching and learning committees were asked to complete a short questionnaire to ascertain whether new students were given any information about the role of academic staff during their student induction. This firstly asked whether the figure of the 'academic', their activities and responsibilities beyond the classroom, and office hours, were introduced as part of Undergraduate Student Induction. Their responses indicated that little is done in this respect, although there was some limited management of expectations: 1. 2. 3. 4. some targeted activity at induction or open days some integration into teaching seminars on ethics/plagiarism and standards which they are accountable some staff profiles in handbooks But there was no consistent responsibility for achieving this. A further question asked how they thought students perceived academic staff and university life, which revealed that they believed students’ perceptions are that: 1. that academic staff have 24/7 availability to answer e-mails 2. hours taught = hours worked 3. feedback to students comprises positive comment and that critical, constructive comment is not feedback 4. academic staff have control over all intangibles Induction activities for new students tended to focus on the responsibility of the students in relation to academic staff, academic practice and the new environment, rather than providing a description of the new roles of both parties. However, respondents suggested that the induction process is already a very overcrowded experience so it was unclear where any additional information would be presented, as course and programme handbooks are not always read and assimilated by new students. Several departments or schools discussed the role of academics as part of general teaching activities, in tutorials, through social media announcements (research achievements, talks, publications) and invitations to research seminars and workshops. Other departments offered seminars on subjects such as research ethics and academic integrity which provided a forum wherein students were themselves treated as ‘young academics’; potentially fostering improved understanding of the role. Some departments broached the role that academics play in HEIs at Open Days. More than half of the respondents expressed an interest in seeing material produced which might help in promoting greater understanding among students of the role of academics. Survey of Students The second part of the research conducted in this case study focused on the extent to which student’s expectations of academic staff might be shaped by their previous experience of teaching in secondary education, particularly in terms of their understanding of what the role of the ‘teacher’ might be and how academic staff might spend their working week. Specifically, this part of the project sought to investigate students’ (i) perceptions of how academic staff approach their working week, (ii) understanding of what a lecturer’s workload includes, what activities lecturers participate in and which of these students believe to be most important, and (iii) opinion as to how students’ perceptions of the academic role might be changed to avoid miscommunication and confusion. Because their expectations about academic staff might be partly shaped by ‘contact hours’ students were also asked about their expectations in this respect. Method Three groups of full-time students were selected to determine whether perceptions changed depending on the year of study: these groups were incoming first years, second and third years, and postgraduate students. Separate questionnaires were circulated via email to each group during the first two weeks of the academic year. This timing was considered to be particularly important for first-year students to ascertain their immediate expectations on arrival. Respondents were also invited to participate in a subsequent focus group, which would further investigate issues arising from the questionnaires. 76 completed questionnaires were received from incoming first years; 54 from second and third years, and 90 from postgraduate students; all subject areas and a broad range of nationalities were represented. A focus group consisting of 12 students drawn from all three groups served to refine the quantitative data. Results 1. Provided with a list of activities undertake by academic staff (other than teaching), students were and asked to rank them in order of importance. They identified that the most important duties for academic staff were research and publishing in academic journals, followed by activities which focused more on supporting students, such as such as offering advice to students on both academic and personal matters, teaching Masters’ students and supervising PhD students. The least important issue was perceived to be recruiting new students and staff. Undergraduate students put more emphasis on staff attending conferences than teaching/supervising postgraduate students, but otherwise the results were relatively consistent between both groups. 2. Second and third year undergraduates and postgraduate students were asked to rank their lecturers and tutors from 1-10 (1=poor; 10=excellent) in terms of the support that they provide in three areas (Figure 1): Student Ranking of Support (i) answering questions (by email or in person from Academic Staff (ii) support in coursework 10 (essay planning, report 9 writing); and 8 6.83 6.53 6.37 7 5.94 5.97 (iii) feedback given (for 5.69 6 essays, exams and 5 coursework). 4 Results were similar for both groups, averaging 6.22 on a scale of 1-10 for all types of support. 3 2 1 0 Answering Coursework Support Feedback given (for questions (by email (essay planning, essays, exams and or in person); report writing); and coursework). New students were not asked this question, as the survey was taken 2nd and 3rd Years Postgraduate early in their academic course and they would be unlikely to Figure 1 have had sufficient experience to answer the question. However, to provide a comparison between perceived support at school versus at university, new students were asked the same question in relation to their secondary school experiences, and their levels of support where identified as high or very high in just over half (52%) of the respondents. As identified in other surveys, particularly the National Student Survey (UK), response times and feedback to students is a key measure that students use to assess the level of support provided by academic staff. Students in the focus group expected that levels of individual support from academic staff would be at a lower level than that provided at secondary school due to the larger number of students within HEIs, as well as the other commitments of academic staff. They also felt that these elements varied widely between staff members, and that students were not always aware of how to address problems, as departmental and university structures for complaints can be difficult to understand. 3. Students were also asked about their expectations in respect of contact hours. Incoming students were asked how much work (contact hours and independent study) they expected to do at University (Figures 2 and 3). Second and third years and postgraduate students were asked whether this was what they had expected before entering university. It might be expected that if new students’ expectations in this area matched the actual experiences of current students, then this may indicate how realistic their expectations may be overall. Figure 1 (first-year students) Figure 2 (first-year students) The expected number of contact hours varied according to programme of study (see Table 1), but a large majority of respondents (79%) expected to receive more than 10 hours of staff contact a week. However, students also anticipated that a lot of work would be undertaken independently with 88.2% expecting that more than ten hours of independent learning would be required to be successful on the course. Overall, students recognised that the amount of time spent on independent study would far surpass the number of contact teaching hours provided by academic staff. The survey results suggested that 65% of current UG & PGT students felt that the amount of work was what they had expected when entering University, with 13% of second and third years and 30% of postgraduate students saying they spent more than 25 hours a week on independent study during the last year. Subject Proportion of time spent on independent Study Architecture 71% Biochemistry and Dentistry 69% Economics 83% English Literature 85% French 86% History 88% Table 1 Proportion of time spent on independent study Discussion The empirical work suggested that students used their experiences of secondary school education as a baseline for understanding their experience at university and for shaping their expectations, although they did recognise that academic staff had a wide range of responsibilities alongside the provision of teaching. Students had a clear understanding that it was important for academic members of staff to conduct research and publish in journals, but their view was that students should be the next most important element of the time of the academic staff, with little support for activities which might be considered more administrative, such as writing grants, carrying out administrative duties, addressing media concerns and attracting and recruiting new students and staff. The implication of these findings is that more needs to be done to inform students about the importance of the broader range of the academic role, and universities need to find ways to deliver a more consistent response to students. This coincides with the view of academic staff. However, there is a tension created between the increased importance of research (at least in part because of the RAE/REF) and a growing proportion of academic time being devoted to administrative activities. Tight (2010) suggests that because overall workload has not increased since the 1960s “the balance of the average academic’s workload has changed in an undesirable way” with teaching being squeezed between research and administration. The focus groups did not identify ways to alter the perception of academic staff in order to address miscommunication and confusion of roles and responsibilities. However, the research suggests how to provide new students with a better understanding of the academic’s workload and priorities, alongside a realistic indication of what they might expect in terms of their own workload and the support that they will receive. Crucially it was recognised that this should be presented in a number of different formats and reinforced over time, rather than being yet another essential communication to be squeezed into Intro Week or the Student Handbook. It was also felt that more could be done to remind academic staff of their responsibilities to students. Conclusion Students’ expectations prior to entering university are reasonably well informed, and rather more realistic than they are given credit for. This discrepancy may well come from students’ actual behaviour once at university reflecting their own immediate needs, stresses and frustrations in real-life situations, which can lead to academic staff having quite a harsh view of the students’ expectations. As a consequence, the issue is less about correcting perceptions than reinforcing them, both at the outset of the new academic year and at key points throughout the year, such as hand in, marking and feedback. It is also important that staff, as well as students, are reminded of their own individual responsibilities and responsibilities to each other with well timed concise and contextual communications.