SACT Workshop Programme - NHS Education for Scotland

Safe Use of Systemic

Anti-Cancer Therapy (SACT).

Workshop for Assessors

Welcome

Aim

The aim of the workshop is to prepare assessors to become familiar with tools and approaches that support a consistent approach to SACT competency assessment

Learning outcomes

By the end of the workshop participants should be able to:

Increase familiarity with NES Education and Training Framework for the Safe Use of SACT

Support work-based learning in the context of SACT competency assessment

Use the NES tools and approaches to competently undertake consistent assessments

Identify sources of help and support

Critically analyse the value of the tools and approaches

Display increased confidence in fulfilling the assessor role

Who should attend the workshop?

He althcare practitioners who have achieved the SACT competencies at ‘Expertise’ in Practice’ level and are involved in SACT competency assessment. Participants are expected to have undertaken previous training in teaching and assessment.

Role of the Assessor

The Assessor’s responsibilities are to:

promote best practice within own area of practice

work with senior manager to agree an action plan to ensure competency assessment of all relevant staff within area of practice

undertake formal assessments of competency

maintain accurate records

provide support and advice to staff

provide additional support to individuals who have difficulty achieving competence

keep senior manager/education provider up to date with progress as appropriate

Nursing

The role of SACT assessor can be undertaken by practitioners who have completed an accredited SACT module or equivalent, and achieved the SACT competencies at ‘Expertise’ in Practice’ level. The assessor is responsible for the final assessment and ‘sign off’. Others may be involved in supervision/ mentorship, supporting development of competence and completion of an individual’s record of achievement. The assessor may also act as mentor/ supervisor, but the final assessment should be a separate event from achieving competence.

Medicine

The role of SACT Assessor can be undertaken by Consultants or Staff grades with a permanent contract, who have been in post for at least 4 years and have completed a SCOTS (Supporting Clinicians on Training in Scotland) course or equivalent.

The assessor is responsible for the final assessment and ‘sign off’and assessment should take place in partnership with pharmacists and relevant nursing staff. Others may be involved in supervision/ mentorship, supporting development of competence and completion of an individual’s record of achievement. The assessor mayalso act as mentor/ supervisor, but the final assessment should be a separate event from achieving competence.

Workshop Outline

Time Content

10.00-10.30 Registration

Content

10.30-10.50 Welcome and introduction

• Group Introductions

• Aims and Learning Outcomes

10.50-11.00 Background

Purpose of the SACT Education and Training Framework

Role of the SACT assessor

11.00-11.30 Using the SACT record of achievement /competencies

Supervised practise / direct observation

Questioning and discussion

Simulated exercises / scenarios

Multi-source feedback (MSF)

Checklists

Suggested activities Resources

Presentation

Discussion

Ask group to share their reason for attending workshop and their experiences of SACT assessment

Presentation

Slides 1-3

Presentation

Group Discussion

Who assesses?

Delegation to mentors / supervisors / MSF

Deciding which competencies are applicable

When are people ready to be assessed / what needs to be in place?

Self assessment

Using checklists

How do you ask / inform patients?

How do you know a competency is achieved?

Tea / coffee (11.30 – 11.45)

The SACT Education and Training Framework

Slides – 4

Handout 1:

Role of the assessor

Slides 8-11

SACT records of achievement

SACT checklists

Time Content

11.45-12.45 Assessing SACT Competency (1)

Facilitating feedback conversations

Content

Ensuring consistency

Questioning, reflection and discussion

Suggested activities

Group activity

In groups of three: one acts as student, one as assessor and one as observer. Group members change roles in the three scenarios below.

Use Enhanced Level competencies for

Assessor questions the student to determine competency

Observer then gives feedback

Assessor and student give feedback to observer

on their feedback

Resources

Slide 12-13

Handouts 2 & 3:

Giving feedback

Record of achievement

Handout 4:

Recording feedback

13.30-14.30 Assessing SACT Competency (2)

Facilitating feedback conversations

Ensuring consistency

Questioning and discussion

Lunch (12.45 – 13.30)

Group activity continued

Group discussion Flip chart 14.30-14.45 Reflection

Main learning points

Changes in practice

Additional learning needs

Tea / coffee (14.45 – 15.00)

Time Content

15.00-15.40 Assessing SACT Competency

Ensuring consistency

Content

Supervised practise / direct observation

Supporting individuals

Managing non-achievement

of competency

15.40-16.00 Closing session

Local policies

Resources

Where to get help and support

Suggested activities Resources

Group discussion

How do you assess competency and ensure consistency now?

What challenging situations have you encountered

when assessing?

How do you manage people who have not achieved

the competencies?

Group activity

Identify top tips for assessing

SACT competencies

Slide 14

Record of achievement

Handout 5: Non-achievement of competency

Discussion

Using scenarios for use in clinical areas

Record keeping

Taking forward – action planning

(implementation into practice)

HANDOUTS

1. Role of the Assessor: Nursing and Medicine

2. General principles of giving feedback

3. Giving feedback: Pendleton’s Rules and Seven principles of good feedback

4. Feedback template

5. Non achievement of competency

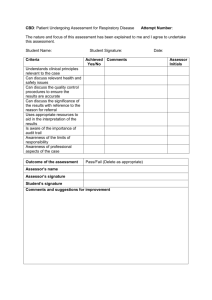

HANDOUT 1: ROLE OF THE ASSESSOR

Role of the Assessor

The Assessor’s responsibilities are to:

promote best practice within own area of practice

work with senior manager to agree an action plan to ensure competency assessment of all relevant staff within area of practice

undertake formal assessments of competency

maintain accurate records

provide support and advice to staff

provide additional support to individuals who have difficulty achieving competence

keep senior manager/education provider up to date with progress as appropriate

Nursing

The role of SACT assessor can be undertaken by practitioners who have completed an accredited SACT module or equivalent, and achieved the SACT competencies at ‘Expertise’ in Practice’ level. The assessor is responsible for the final assessment and ‘sign off’. Others may be involved in supervision/ mentorship, supporting development of competence and completion of an individual’s record of achievement. The assessor may also act as mentor / supervisor, but the final assessment should be a separate event from achieving competence.

Medicine

The role of SACT Assessor can be undertaken by Consultants or Staff grades with a permanent contract, who have been in post for at least 4 years and have completed a SCOTS (Supporting Clinicians on Training in Scotland) course or equivalent.

The assessor is responsible for the fi nal assessment and ‘sign off’ and assessment should take place in partnership with pharmacists and relevant nursing staff. Others may be involved in supervision/ mentorship, supporting development of competence and completion of an individual’s record of achievement. The assessor may also act as mentor/ supervisor, but the final assessment should be a separate event from achieving competence.

HANDOUT 2: GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF GIVING FEEDBACK

From NES Communicating, Connecting, Caring www.nes.scot.nhs.uk/education-and-training/by-theme-initiative/ communicating-connecting-caring/developing-others/reviewing-practice-and-giving-feedback/giving-feedback.aspx

Being able to give constructive feedback is crucial in supporting others to improve their communication and relationship skills and approaches.

Sometimes feedback can be given on the go during daily practice and other times it is more planned such as appraisals, re-registration or annual development reviews. Either way, it is best done using a framework that provides constructive, specific and useful information on what is being done well and what could be improved. The goal should be to support ongoing improvement in practice by encouraging self-awareness and stepwise change.

General Principles for Giving Feedback

Before the Feedback Session:

Make sure the practitioner is expecting to receive feedback.

Find out if the practitioner wants to develop a particular aspect of communication.

Be clear about the purpose and outcome of the feedback.

If observing a particular interaction find out what the practitioner was hoping the interaction would achieve.

Be clear about what standards are expected.

Gather appropriate evidence.

After Observing an Interaction

Give feedback as soon as possible after the event.

Ask the practitioner to reflect on their own performance first, and to be positive.

Ensure your feedback covers positive aspects as well as areas for improvement.

Be descriptive rather than evaluative.

Focus on a few elements.

Be specific, not general.

Refer to behaviours that can be changed and not personality traits.

Encourage the practitioner to suggest and practise alternative approaches.

Before the Feedback Session:

1. Prepare for Feedback

It is important that practitioners get regular feedback on their communication and relationship skills throughout the year, not just in an annual review. Remember that a key principle of any development review process is ‘no surprises’.

It is helpful for the practitioner to know when feedback is coming, especially if it requires more discussion. It can be particularly disheartening for a practitioner to receive negative feedback when they are not expecting it. Ideally, you and the practitioner will be operating as part of a team or organisation where ongoing review and improvement of communication with patients is the cultural and organisational norm. They should know in advance that at least part of what is being observed in a given interaction is their communication ability and that they will receive feedback to help them improve.

In some situations you will have to give feedback without any opportunity to prepare, for example, if you observe particularly good poor practice or particularly bad practice. However even in these unplanned situations you can still use principles to inform how you give feedback.

2. Find out if the practitioner wants to develop a particular aspect of communication.

In order to make the most of any time available, it is useful to find out in advance which particular abilities the practitioner is hoping to develop or has found problematic. A practitioner may have discovered through reflection or self review that they want to improve on a particular aspect. Identifying this beforehand enables the observer to listen out for it and then provide the most relevant feedback.

3. Be clear about the purpose and outcome of the feedback.

Ensure that the practitioner understands the purpose of the feedback. Ideally, the purpose will be about supporting them to reflect on their own skills, encouraging them to try new approaches in order to continually improve their skills and enabling them to continually improve in a supportive environment.

The parameters for future action should also be clear. If issues arise, how can the practitioner be supported to address them?

What limitations exist, for example, lack of time, expertise or development opportunities?

4. Find out what the practitioner was hoping the interaction would achieve.

Make sure that you understand what the practitioner was hoping for from the interaction. That way, it will be possible to assess whether the communication strategies that they have used have been successful when measured against their own criteria.

This will prevent you making comments based on your assumptions about the situation. Bear in mind that a person-centred approach also involves the practitioner identifying what the patient expects and hopes to get out of an interaction and that a balance is required.

5. Be clear on what is expected.

It is helpful if the practitioner and observer have a shared understanding of the criteria on which the feedback will be based.

Both should know what is being reviewed, for example, standards, principles, models or elements of communication to be demonstrated.

6. Gather appropriate evidence.

For regular, on the job, feedback to practitioners about individual conversations, your own notes or even better notes based on a simple checklist or framework completed by the practitioner themselves or by an observer (for example, you) will suffice as support for feedback.

For annual reviews of communication and relationships, it would be more appropriate to use evidence that demonstrates ongoing learning over the year, for example, reflective notes from the practitioner or from someone who has observed their skills developing over time, a series of completed observation checklists, feedback gathered from patients over a period of time

(formal or informal) and so on.

The use of evidence for KSF annual development reviews is discussed further in the Guide to KSF and Communication and relationship Skills

After observing an interaction:

7. Give feedback as soon as possible after the event.

Feedback should be timely, ideally given immediately after an interaction has been observed so that events are fresh in the mind and there is less opportunity for doubt over what actually happened. This also means that it should be easier to generate ideas for how a situation might have been handled differently.

8. Ask the practitioner to reflect on their own performance first, and to be positive.

Asking a practitioner to reflect on their performance first before they receive feedback allows them to raise any shortcomings before they are pointed out by anyone else. This should reduce the chance of demoralising them.

Some practitioners will be quick to highlight areas of difficulty. Help them to identify elements of their performance that they feel were good and should be continued as well as areas where they felt things went less well and could be improved. Make sure that the practitioner understands that learning through observation and feedback is a collaborative process and that their self-reflection is an important part of this.

9. Ensure feedback covers positive aspects as well as areas for improvement

There is an opportunity to learn from identifying elements of communication that have worked well and should be continued as well as elements of communication that could be developed or improved. This is especially true in a group situation where participants will have different strengths.

10. Be descriptive rather than evaluative

Focus on what was actually said and done rather than how you felt it went. Be careful to describe what happened and what the consequence was. Then encourage the practitioner to reflect on this. Avoid making assumptions about feelings and also adding your own feelings about an interaction. Avoid accusing or blaming the practitioner.

For example, “When you turned to the computer screen, eye contact was broken and the patient stopped talking” rather than “You didn’t make a very good job of encouraging the patient to talk”.

11. Focus on a few elements

If there are several issues that need addressing, choose the most pressing as it will not be possible for the practitioner to take in feedback on all of the elements at once and having too many areas highlighted for improvement could also be demoralising. Be selective and focus on two or three areas that could be changed and remind yourself to look out for the other areas on a different occasion.

12. Be specific, not general

Make reference specifically to actual parts of the interaction rather than making vague generalisations. Give examples of what was actually said or done and what the patient response was.

For example, “When you asked an open question at the beginning you gave the patient an opportunity to explain their ideas and concerns in their own words” rather than “you started off well”.

13. Refer to behaviours that can be changed and not personality traits

Focus on what is actually said and done and could be either repeated or changed another time. Be sensitive to elements of an interaction that relate personal characteristics or features that might not be changed. Try to phrase feedback so that the focus is non-judgemental and refers to the behaviour rather than the person. For example,

“Throughout the consultation you were talking a lot of the time and there weren’t many pauses” rather than “You are quite a chatterbox, you didn’t let him get a word in edgeways!”

14. Encourage the practitioner to suggest and practise alternative approaches

If the practitioner is struggling to think of different approaches, make suggestions or recommendations

HANDOUT 3: GIVING FEEDBACK

From the NHS Education for Scotland Train the Trainers Toolkit www.nes.scot.nhs.uk/education-and- training/by-themeinitiative/facilitation-of-learning/train-the-trainers-toolkit-resources.aspx

Feedback 3

More detailed feedback can follow Pendleton’s Rules:

Briefly clarify matters of fact

The learner goes first and discusses what went well

The trainer discusses what went well

The learner describes what could have been done differently and makes suggestions for change

The trainer identifies what could be done differently and gives options for change

David Pendleton is a Chartered Psychologist who with Dr Theo Schofield, Dr Peter Tate and Dr Peter Havelock wrote

The Consultation in 1984 which included advice about how to give feedback and this was labelled ‘Pendleton’s Rules’.

Pendleton D, Schofield T, Tate P, Havelock P (2003) The New Consultation: Developing doctor-patient communication.

Oxford Medical Publications, Oxford

Some strengths of Pendleton’s Rules

1. Offers the learner the opportunity to evaluate their own practice and allows even critical points to be matters of agreement.

2. Allows initial learner observations to be built upon by the observer(s).

3. Ensures strengths are given parity with weaknesses.

4. Deals with specifics.

Some difficulties with Pendleton’s Rules

1. People may find it hard to separate strengths and weaknesses in the formulaic manner prescribed.

Insisting upon this formula can interrupt thought processes and perhaps cause the loss of important points.

Though it sets out to protect the learner, it is artificial.

2. Feedback on areas of need is held back until part way through the session, although learners may be anxious and wanting to explore these as a priority. This may reduce the effectiveness of feedback on strengths.

3. Holding four separate conversations covering the same performance can be time consuming and inefficient.

It can prevent more in-depth consideration of priorities.

Feedback 4

The seven principles of good feedback practice (HEA 2004)

1. Facilitates the development of self-assessment (reflection) in learning.

2. Encourages teacher and peer dialogue around learning.

3. Helps clarify what good performance is (goals, criteria, standards expected).

4. Provides opportunities to close the gap between current and desired performance.

5. Delivers high quality information to students about their learning.

6. Encourages positive motivational beliefs and self-esteem.

7. Provides information to teachers that can be used to help shape the teaching.

HANDOUT 4: FEEDBACK TEMPLATE

Feedback template

Practice giving non judgemental, specific and descriptive feedback

What was done well?

What needs development and worked on?

From the NHS Education for Scotland Train the Trainers Toolkit www.nes.scot.nhs.uk/education-and-training/by-themeinitiative/ facilitation-of-learning/train-the-trainers-toolkit-resources.aspx

What are the options for change?

Agreed action plan

HANDOUT 5: NON-ACHIEVEMENT OF CLINICAL COMPETENCY

In event of an individual not achieving clinical competency feedback a discussion should take place with that individual.

An example of how this might be managed is provided below. NHS Boards may choose to adopt or amend this example in line with their local policies and procedures.

Initial assessment

The assessor should report non-achievement of competency to the relevant senior manager.

An action plan to address the specific areas of non-achievement and timescales should be agreed and documented.

The individual should be re-assessed at the end of time agreed in the action plan by the same assessor.

It is recommended that individuals do not administer SACT unsupervised during this period.

Second assessment

If an individual does not achieve clinical competency following a second assessment, the assessor should report again to the relevant senior manager. A supervisor will work with the staff member on a one-to-one basis to help them achieve the necessary competence and a third and final assessment should take place within four weeks with a different assessor.

Third assessment

If an individual does not achieve clinical competency following a third assessment, the assessor should again report to the relevant senior manager. It willbe the responsibility of the manager to make a decision about the involvement of the individual in SACT administration.

Example of management of non-achievement of competency

Contact

NHS Education for Scotland

Westport 102

West Port

Edinburgh

EH3 9DN

Tel: 0131 656 3200 www.nes.scot.nhs.uk