The Pediatric Medical Home: Results From a Systematic Literature

advertisement

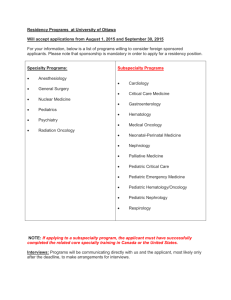

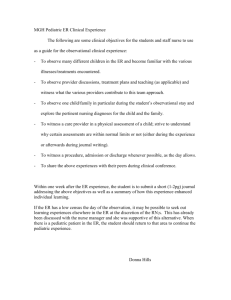

The Pediatric Medical Home: Results From a Systematic Literature Review Presenters: Debra Tan & Bita Kash, Texas A&M University Recorded on: March 4, 2015 Perfect. And now let's go on with today's presentation. Debra, Bita? Hi this is Dr. Bita Kash, and welcome everybody. I would like to introduce to you a future doctor Debra Tan, who has been engaged in this research project this year was Texas Children's. And we have learned a lot together. And she will be presenting results of our research, that's been mostly focused on taking a researchinformed approach and expanding the already existing pediatric medical home at Texas Children's. So, here's Debra. >> Hi everyone, thank you Doctor Tomachevski and Doctor Kash for that kind introduction. So let's get started on the Pediatric Medical Home, which contains the results from the systematic literature interview. And just to let you guys know that we've been working with Kay Tittle, the president of Texas Children's Pediatrics, on this project. So, before we get started, let's go over the brief history of the pediatric medical home. The pediatric medical home concept was first introduced by the American Academy of Pediatrics, also known as AAP, Back in 1967. Initially, the AAP designed the medical home as a center of a child's medical records. At the time the care, of children with special health needs was the primary focus of the medical home concept. However, over time, the definition of the medical home has evolved to reflect changing needs and perspectives in health care. Today the medical home expands upon it's original foundation, becoming a home base for any child's medical and non-medical care. The medical home model is purposed with delivering primary care that is accessible, continuous, comprehensive, family centered, coordinated, compassionate and culturally effective to all children. And especially, the children with healthcare needs. And defined patient centered and family centered as a partnership among practitioners, patients and their families, to ensure that decisions respect patient's wants, needs, and preferences. And that patients have the education and support they need to make decisions and participate in their own care. Comprehensive care means that a team of care of providers is wholly accountable for a patient's physical and mental healthcare needs, including prevention and wellness, acute care, and chronic care. Coordinated care means care is organized across all elements of the broader healthcare system, including specialty care, hospital, home healthcare, community services and support. Accessable means patients are able to access services with shorter waiting times, after hours care, 24/7 electronic or telephone access and strong communication through health IT innovation. These elements are shown in the rainbow house puzzle on the slide to illustrate that each element is very important in forming the medical home. Interest in the medical home model has grown exponentially across many spectrums of the healthcare system, and has been a primary focus of the US health system reform, and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act in 2010. The pediatric medical home can serve as a way To revitalize the field of primary care, and encourage medical students to specialize in primary care. The pediatric medical home concept also serves as a method to enhance team-based care, enhance access to care, and lower health care costs. So what do we know about the pediatric medical home model? Studies regarding the pediatric medical home model remain formative and fragmented. The peer reviewed literature have show dissimilar results as well as inconsistencies in the definition of the medical home. There is also variation in the assessment of the performance and outcomes with regard to the medical home. Since less is known about the model's implementation in practice of everyday pediatric primary care, there is plenty of room for learning and informed decision-making, when considering the development and implementation of innovative, pediatric primary care models. Our industry partner, Texas Children’s Pediatrics, currently has a pediatric medical home in place. They have been the leaders in the field, and are now looking for ways to target specific populations. Therefore, our objective of this study is to make evidence-based pediatric care models, or pediatric medical homes, easier to implement by using a patient-segmentation approach. The patient-segmentation approach utilizes a framework based on value for patients. The mean idea is that primary care should be organized around specific subgroups of patients with similar needs. These patient subgroups are integrated with relevant and specific specialty providers. And, each patient's outcomes and true costs should be measured by the sub-group that they are in, as a routine part of care. This framework addresses the issue that not one size fits all, as every child is extremely different, especially for children populations with special needs. Medical home care should be tailored differently across populations. In this study, we would like to define operational, staffing, and financial details of the relevant models for future medical home implementation, as well. So, for the methods, our systematic literature review, we searched the Medline Ovid database for the keyword pediatric primary care and pediatric medical home. An additional recursive search was conducted in Google scholar, to identify any missing literature. And recommendations from industry members was also taken into account in the literature search. For our research framework, we applied our literature results to Porter and Colleagues' Patient Segmentation Framework, and assigned these studies and care plans to five various subpopulation groups. For inclusion criteria, we wanted studies that had data specific to pediatric primary care, as well as the pediatric medical home. We excluded all studies that had non-empirical data, non-peer reviewed articles, medical case studies, articles not published in the English language, and that aren't from the United States, and published abstracts. Here's an example of our application of Porter and Colleagues' Patient Segmentation Framework. It's a little busy looking, and I don't want to spend too much time on this slide, but, here you can see that the population is broken down into five subgroups, as we discussed earlier. The patient segmentation approach utilizes the framework based on value for patients. The main idea is that primary care should be organized around specific subgroups of patients of similar needs. The subgroups here are healthy children, defined as children in good or excellent health, with no ongoing physical, emotional and social health care needs. Healthy children with a complex, acute illness defined as children in good overall health, with a complex, acute illness. Children at risk, which is defined as children who are currently in good health but at elevated risk for developing acute or chronic disease, and require a higher level of service. The next segmentation population is children that are chronically ill. And these are children with one or more chronic conditions, with ongoing impact of functional status or post risk for long-term complications. And the last patient segmentation population are children with a complex illness defined as children with multiple chronic diseases, with complications, or otherwise disabling conditions that require care from multiple specialty services and frequently lead to hospitalization or emergency department use. Again, the idea is that the approach would help us learn more about specific pediatric medical home delivery and how care varies across specific patient populations. Here are our results from our systematic literature review in the form of a flow diagram. The computer assisted search yielded 200 potentially relevant citations after the initial review. 174 titles were potentially appropriate and these abstract for review. 31 of these articles did not meet inclusion criteria. Where 13 lacked imperial data, two were case studies, seven were not from the United States, and nine studies were not in the English language. And subsequently, 143 articles underwent full text review. 49 of these articles were excluded as all of these states did not have relevant information or data specific to the pediatric primary care or the pediatric medical home. So this left us with a total of 94 studies that met all inclusion criteria, with additional 13 studies recursive literature, and two additional studies recommended by our industry partner. After assessing a total of 109 articles, we chose seven to present to you today. The seven studies are Limited English Proficiency Latina Mothers in the Pediatric Medical Home. High Functioning, Quality Primary Care Practices. Pediatric Emergency Care Model. Building Healthy Children: Home Visitation Integrated with Pediatric Medical Home. Mental Health Issues in the Medical Home. Clinical Quality Improvement for Identification and Management of Overweight Children in Pediatric Primary Practices. And Responding to the Developmental Consequences of Genetic Conditions. These seven studies all hold very informative, unique, and original designs. The data and results from each of the seven studies have been dissected and information regarding key priorities, care team responsibilities, and care team compositions were chosen to be applied to the Porter and Colleagues framework and will be explained next. The first population segment is the healthy children population. The model limited English proficiency Latino mothers and the pediatric medical home by decamping colleagues, discusses the views and experiences of Latina mothers with regard to expectations for pediatric primary care, since form medical home of limitation and practices serving large, limited English proficiency populations. A healthy children sub-population is designed as, again, children in good health or excellent health with no ongoing physical, emotional, or social healthcare needs. An example of this model is a four year old Latina girl with onset of the flu from a family with limited English proficiency. And to keep it simple, for this model we will keep our focus on key priorities. The model highlights child and family engagement and a high quality parent and provider relationship. For example, does the physician take time to joke with the child and family, or does the physician take time to ask the child and family how they were doing? Another key priority that mothers emphasize for their child with provider continuity. In Decants and Colleagues' qualitative study, most families did not have continuity with one provider, and care coordination with referral to specialty care was also a key priority since most families were required to arrange specialty appointments themselves, and this wasn't the most successful method for them. Again, this population segmentation is the healthy children population, and utilizes the study by Sensky and Colleagues that made psych visits to 23 high performing primary care practices. In terms of the key primary care services needed, this model emphasizes reducing work through previsit planning and pre-appointment laboratory tests. This builds capacity by transforming the roles of medical assistance, licensed practical nurses, registered nurses, and health coaches to promote partial responsibility for elements of care. Physicians like this best since cases were identified in advance, which made their work day easier and enhanced job satisfaction. Another area needed is telemedicine to reach more patients to help alleviate future primary physician shortages. Other key primary care services needed included saving time by re-engineering prescription renewal work out of the practice. Because managing calls, emails, and faxes regarding prescription renewals remains a huge burden and depletes numerous health care resources. This population's segmentation is also the healthy children population, and discusses the pediatric emergency care model. Numerous studies have found that children are continuously taken to primary care offices by there parents or care givers at the time of an emergency. During these urgent situations, primary care providers may be required to provide emergent care in their offices for children with these conditions as they wait for the arrival of EMS personnel. Thus, it is very important to prioritize office based self assessment, office readiness, and documentation and standardization. An office based self assessment should be done to analyze what type of patients and emergencies have already been experienced or may be seen in the future. Reviewing answers from a standardized office based self assessment can help inform primary care practices in making knowledgeable decisions, identifying gaps, and optimizing office readiness. Appropriate equipment such as airway equipment and medications to assist in pediatric medical emergencies should be available at all times to maximize office readiness. Documentation regarding patient triage and office flow is the most important and effective tool for risk management in pediatric office emergencies since it improve efficiency and promotes ongoing care, especially during transfer of care for the child. The next patient segment population is healthy children that have a complex acute illness. These are children with good health, that have emotional, or social health care needs. The model that fits into this patient segment is the Building Healthy Children, BHC, Collaborative, which is a unique model that integrates home visitation into the medical care of infants born to young, low-income mothers with mental health and domestic violence issues. The key potential members include parents or caregivers, pediatric primary care providers, outreach workers, and social workers. Outreach workers and social workers play a vital role in this model. Outreach workers are assigned to various families based on ethnicity and culture, to provide consistent support and encourage a nurturing relationship that helped retain families in the program. Outreach workers meet with families at least bi-monthly to assist with goals related to their individualized service plan. And also provide immunization outreach, help parents get ready for organizing base treatments, and move families toward behavior Change. This study found positive results, such as high retention rates and answered the multi-dimensional needs of young, at risk families. The next model is mental health issues in the medical home, which addresses the at risk children population. Medical and behavioral comorbidities can be difficult for patients and families, and fragmented care, for these patients, result in poor outcomes and higher healthcare costs. Therefore, integrating the management of behavioral health conditions into the primary care setting, such as the medical home, have the potential to improve quality of care for patients while reducing healthcare costs. Focusing on key potential members, parents or care givers, pediatric primary care providers, nurse and medical assistants, education specialists and behavioral health specialists all play a vital role in providing high quality health care to the child. Pediatric primary care providers should help children and families who are resistant to seeking mental health care due to stigma and be able to recognize emergent situations that would require immediate. Nurses should learn to conduct routine, developmental screenings as well as complete assessments in conjunction with performing other tasks such as weighing and measuring the child. Behavioral health specialists also play an important role and can help develop primary care intervention teams that involve multi-disciplinary providers within pediatric primary care clinics. The next population segment is the chronically ill population. This includes children with conditions such as hypertension, high cholesterol and, or obesity. In most primary care settings today care coordination and case management can become so complex for primary care providers that communicating with several specialists and gathering clinical information can become time consuming and daunting. This model discusses the identification and management of overweight children and integrates life coaches and nutritionists into the care plan to target increased physical activity and a healthy diet. The model also emphasizes the importance of early screening and prevention in the pediatric primary care setting. Opening health clinics with a focus on multi-disciplinary in search of education to target more rural populations, and patient consultations for overweight medical management, coaching calls to go over improvement plans and counseling with a nutritionist or dietician. The last patient segment is children with a complex illness. These are children with multiple chronic diseases or complications that are disabling and require rigorous care. An example of this child would be a 14 year old boy with cerebral palsy who has been hospitalized twice in the last year. The key part is for this model includes screening for developmental differences early in the child's life, if it hasn't already been diagnosed, as an ongoing process for the child. Early intervention for children with established conditions causing developmental delays and support for families of children with disabilities and avoiding adverse events where the child ends up in the hospital is also a priority. This can be very important for the parents since it can be very difficult to understand their child's diagnosis and sometimes the child would need to repeat the diagnostic process at intervals. The child population segmentation framework adopted by Porter and colleagues can be applied to the pediatric medical home model to improve quality of care for children, as well as reduce health disparities and healthcare costs. The concept of the pediatric medical home and the implementation process remains complex. It’s important we try to identify and understand best practices so they can be applied to specific targeted patient populations. And, that is all I have. Thank you. Do you have any questions? >> Thank you very much for your presentation. And I now unmuted everyone, so, please feel free to ask the presenters any questions. >> Hi, it's Dr. Ian from Heimwork in Pennsylvania. Good morning, good afternoon, whatever. >> I have a comment as well as well as a question, if you don't mind. Heimwork isn't insured, as you all know, in Pennsylvania. We've had a pay for value medical home program, gosh, for about three years now. That includes pediatrics as well as all primary care and really in sense in the medical home model. Our model is actually similar to the alternative quality contract studies, also in house affairs from the Massachusetts area that uses quality as well as care cost trends to determine the appropriate incentives for our medical home practices. And one of the big dilemmas we've had in the pediatric population is that, for the pediatric population if you look at total care costs, the total care costs range about $200 per member, per month. For comparisons sake in the commercial adult population, you’re talking about $500, give or take, per member, per month. And in the Medicare population, you’re talking about somewhere close to $1000 per member, per month. So as you can imagine, obviously the focus is on quality and access, but we look for financial results in the care cost trend piece for that population attributed to a practice, specifically in this case pediatric practice. And I know this sounds like a very lengthy piece, but what it's leading up to is this. So in a $200 per member, per month population, those care cost trends are far more variable based on some of the population segmentation that you noted from Porter and such, but also it's just because of the relatively low dollar amount compared to the other populations, meaning adult and commercial, so we've really struggled with that. And If you have just a few very ill children or if you have a population of birth to 12 months of age that are influxed into your practice that could really change the care cost trends for that population. I don't know if y'all have, and maybe that's the next evolution of your study on the pediatric medical model, cuz I really do believe that without appropriate incentives, financial incentives, whether it's the pediatric model or any model of medical home, is somewhat doomed. But we've struggled in trying to determine appropriate incentive, financial incentives in the pediatric population medical home because of that care cost trend dilemma. I just, again, it's kind of more a comment, the question that y'all has similar in your research or your thoughts. >> Thank you Dr. Bloschicak, I appreciate that comment. It's clearly something that we both on the research side and practice side need to work on in developing value-based. I think what our value-based purchasing should be based on these type of segmentation strategies. Let me see if I can go back here. One of our our goals for the future would be to really try to quantify what it takes to take care of different segments of pediatric patients. As primary care is becoming more specialized really, so a $200 per patient cost will not apply to all these different segments. So what we are trying to do next is try to figure out based on the key team care team members you need and a fixed-cost in developing some of these programs, then what's the real cost and benefit of each one of these segmented, targeted programs? So depending on which program you want to embrace. Really your cost structure will be different, and that should be also incorporated into the incentives and the pay for value methodology. >> Yeah, I agree. And again, it was more of a comment that we've had more struggles in the pediatric population in determining appropriate incentive and how to determine the incentives. As well as how to illustrate the return on investment, illustrate value to our customers, the purchasers. >> Right. >> Because of that. >> I absolutely, yeah. And go ahead. >> I was gonna say, because you're starting out with an overall population per member, per month cost of 200. And $10 either way is a care cost trend of what, 5%. >> Absolutely. And that's where we hope, as child researchers, we can help our health care system, our members in making a case for showing that we might be different and we even within let's say say healthy children with complex acute illness depending on which model you choose, you have a different cost structure. Right, right. >> You know that I find that thankfully the quality measures that are nationally accepted for both primary care and pediatrics specifically are pretty well refined and defined. But the financial piece of this which is just as important for long term survival is not as well studied or defined. >> Absolutely. >> This is Jennifer DuBois from Georgia Tech. And we're actually doing a research project looking at adult clinics but looking specifically at design. I'm in the college of architecture, and looking at the design of the team room. And I was just wondering, we didn't find a lot of information out there, but I was wondering I know it's not what you were looking for but did you come across any literature about either the design of the space or the clinic or the team room or kind of keys to success for how that needs to be or needs to be different to accommodate medical home models verses a traditional clinic model. >> Hi Jenifer it's Debra. I actually did not find anything related to architecture or the way things are modeled in the hospital. Yeah. >> All right, well. That mirrors what we found in the adult population. >> Yeah. >> I do, maybe. Jennifer want to connect you with our school of architecture. It has a center for healthcare design and we collaborate with them quite a bit on projects and proposals. >> Yeah and we're from and and >> There we go >> You've got the right people. Yeah. So talk to Curtis about that. >> Yes I'll do that. So if you didn't see anything about architecture is there anything you can draw from all the literature that kind of says what needs to happen to make it successful? Like what differentiates successful implementation of PCMH versus clinics that maybe have decided it didn't work out so well or have abandoned it? >> Well, that's at two levels, Jennifer. Really, I think the reason we did decide to use Porter's model was because we were seeing more evidence in programs that are very targeted to a very narrow segment of patients. So if you look at the literature in order to find real evidence based models you will end up with a very narrow targeted patient type models. >> Mm-hm. >> So then we thought hey, we really think then Porter is right, right? Maybe we should use his framework, and then at the second level of what this research hopefully will help us with the cost structure as well is we see that the key care members, the team, is quite different. And so that also gives you an idea of how to compose a team, operationalize it, and then how much it might cost you. >> So, in general, would you say it's PCMH is more successful the more specialized the patient population? >> Absolutely. >> Or is it rather that as long as it's not, if you just have a bunch of healthy patients, it might not make sense. >> Well, even within healthy children, you need to, if you take a look at within healthy children>> Right, dealing with the healthy children, these were still special segments that we>> We>> Identified>> Exactly, we found evidence for positive results. And you look at healthy children, there's three segments within healthy children. >> Right, but those are all like subsets. >> They are subsets, or they're all decisions to be made by the practice. Which one of these am I going to primarily be? You can't be all. >> Yep, thanks. >> Thank you. >> Does anyone else have any questions, this is a great discussion, thank you very much. >> Did you find any, this is Jennifer again, did you find any great statistics about successes right that can be quoted of in a, just kind of goes back to the previous question right, but any success stories that overall it's showing, any trends I guess, that it can save money, have better health outcomes? >> Yes we found positive benefits for patient segmentation population. So we think that it is a very promising model to further study and so. >> That's something that Jennifer would be good for us to maybe give even though it might just be one study, to give an example of what the impact in dollars might have been. I think maybe that. >> Or in health outcomes. >> Yeah, so yes, these models that we present here today clearly showed better health outcomes or a reduction in hospitalizations so cost of care. So that's something we would want to highlight. Usually that's a good reminder of it because as researchers you forget to really highlight the impact and you highlight your limitations, but I think it's important for us to do that. >> Right, right, but what is it you can tell us, what can you say, you've got all these articles, and we haven't. >> Right, so adding those dollar signs or better outcomes is something we should include. >> Mm-hm. Hi it's Jamie Blunt checking in, I think that's a great, great plan. You know the studies I've read as well as our experience here in Pennsylvania and in our medical home effort here in Pennsylvania we have about 1.1 million members now being cared for in the medical home environment. And that's all primary care, pediatrics as well as adult medicine. And we've seen reduction in emergency room utilization, which I think you pointed to. And we've also seen improvements in the cost of prescription drugs. And overall the care cost trend blessed in the market by about 0.5%. But probably just as important is something that sometimes is missed is patient satisfaction increased as well as physician and non-physician practitioner satisfaction increased in a lot of the models. Now I know that's not uniform throughout but I think that's an important point as well. >> Very important point. I think most of these studies do report patient satisfaction mostly. That's the number one reported outcome. Yeah, but we have not been, I mean that's one that is hard to quantify at this point but we will add a column to this. This is great suggestions thank you to all of you. We will add a column to these slides and try to record impact. >> Great. Well thank you everyone for your conversation and also for your questions. We really appreciate it. Yeah, this is good. Thanks. So everyone will soon be posting this webinar on the CHOT web members section so please if you have any colleagues who were not able to attend today's webinar let them know that it will be there by Friday. And please let us if you have any more questions shoot us an email either to myself or Dr. Kash or Deborah. And we look forward to seeing you guys, or at least hearing you guys at the next webinar, which will be on April 1st. Have a great afternoon everyone. >> Thanks. >> Bye. >> Thank you. >> Bye.