Katrina

advertisement

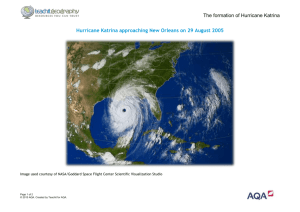

Sarah Cazenave MC 2001 Steve Buttry Katrina Takes Aim Early in the morning on August 29, 2005, Hurricane Katrina made landfall on the Gulf Coast. With sustained winds of 100-140 miles per hour and a stretch of 400 miles, Katrina measured as a Category 3 Hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale. Although Katrina heavily targeted many parts of Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama, New Orleans endured most of its catastrophic effects. Due to breaks in the faulty levee system, New Orleans quickly flooded under the hurricane’s pressure, leaving the city a wasteland of devastation. For my project, I will research and analyze the coverage of Hurricane Katrina by The TimesPicayune, a local newspaper in New Orleans, and 1 Dead in Attic, a collection of stories by Times-Picayune journalist Chris Rose. However, before I get into more detail on the coverage of Hurricane Katrina, I want to address why I chose this particular topic. Although my family lives in Baton Rouge, we were still affected by the destruction of the hurricane. Many of my relatives lived in New Orleans at the time, so most of them came to live at our house when it hit the city. Think about it. Twenty people in one, not particularly large, house. Needless to say, it was utter chaos. As a nine-year-old at the time, I was overjoyed. It was like Thanksgiving every day, except without the large feast. I could play board games and hide-and-seek with my cousins all day, and the electricity going out was just a lucky addition to our games. I didn’t understand that outside my personal playground was the destruction of my favorite city. I didn’t understand that my cousins would have no house to return to after they left. I didn’t understand that, while I was happily playing, scenes of floodwaters and people calling out for help were being shown on the television behind me. Once it was time for my family to leave, I remember walking up to my mom and asking, “Can we do that again?” The absurdity of it. On August 28, the day before Katrina hit, New Orleans Mayor Ray Nagin issued the city’s first mandatory evacuation order and declared that the Superdome be used as a shelter for those who could not leave. By nightfall, almost 80 percent of the city’s population evacuated the city. Some sought shelter in the Superdome, while others chose to wait out the storm at home. Once Katrina hit, people became desperate for news of their beloved home. Those fortunate enough to have power crowded around their TVs and radios, hoping for any hint at the well-being of their own homes. Despite the printers being out of commission, local newspapers continued to update citizens on the state of their city either through an affiliated website or blog. Coverage of Hurricane Katrina The Times-Picayune One of the most significant and notable newspapers to continue publishing during Hurricane Katrina was The Times-Picayune, which was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Public Service in 2006 for its coverage of the hurricane. The Times-Picayune played a large part in updating the public during the storm and continued for years after in repercussions and editorials. When Hurricane Katrina approached on Sunday, August 28, 2005, dozens of the newspaper’s staffers refused to evacuate and rode out of the storm in the center of the newspaper’s building, sleeping in sleeping bags and on air mattresses. They stayed in a small room referred to as the “Hurricane Bunker,” and posted continual updates on the paper’s affiliated website. Since they could not deliver newspapers to people’s houses, newspaper and web staffers produced a “newspaper” in electronic format. On The Times-Picayune’s affiliated website, NOLA.com, evacuated New Orleans and Gulf Coast residents began using the site’s forums and blogs, posting pleas for help, offering aid, and communicating with rescue workers. The electronic newspapers and blog allowed The Times-Picayune to reach a wider audience and alert the citizens in other states on the condition of New Orleans. http://media.nola.com/hurricane_impact/photo/catastrophicheadlinejpg-e2578548ae6120af_medium.jpg Additional examples of these “electronic newspapers” can be found here: http://www.nola.com/katrina/pages/ The Times-Picayune’s blog during Katrina: http://www.pulitzer.org/archives/7072 Time-Picayune’s Award Winning Coverage Gallery: http://www.nola.com/katrina/#/4 Rising floodwaters forced 240 Times-Picayune staff and their family members to flee the paper’s downtown offices in delivery trucks on August 30. However, a small group of photographers, reporters, and editors stayed in the area continuously, and the newspaper never ceased publishing and posting online editions. Some journalists worked out of the Manship School of Mass Communications at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge. In an interview with Jim Amoss, The Times-Picayune’s chief editor, at Washington, D.C.’s Newseum, Amoss commented on the courage of the reporters who stayed in New Orleans during the storm: [Referring to two journalists] “They looked down from the railroad bridge, and in what used to be a quiet residential street is now a torrent, a river that is rushing past them under this bridge towards downtown New Orleans. And in that flash of the moment they both realize that we’re doomed, that the water has broken through the flood walls and that the oceans are rushing into the city.” What separates the coverage of Hurricane Katrina to other news stories is the fact that the reporters and journalists are essentially reporting on their own lives. In other news stories, the journalists maintain a distinct barrier between themselves and the subject they are covering. However, what happens when that barrier is broken? What happens when the journalist himself is involved in the story he is covering? Unfortunately, this is what occurred during Hurricane Katrina. Despite being emotionally attached to the events, the journalists still had to set aside their own anger and sadness to capture the facts to communicate to the public. In his interview, Amoss comments on this particular aspect of the coverage of Hurricane Katrina: “One of the things that is most admirable about the journalists is the way in which they were all personally affected by the very story they were covering…At the moment that he is jotting things down in his notebook he is also realizing that his house is gone, that it is completely underwater and he pauses for maybe a minute to absorb that fact and then he takes up his notebook again and continues writing because he is a journalist and it is a mission.” Media Coverage of Hurricane Katrina (Newseum): http://www.c-span.org/video/?2951951/media-coverage-hurricane-katrina 1 Dead in Attic by Chris Rose In order to further expand the coverage and destruction of Hurricane Katrina, Chris Rose, a Times-Picayune columnist, published a collection of stories recounting the first four months of life in New Orleans after the storm. Throughout the book the reader essentially follows Rose in his discovery of the devastation of New Orleans and journey to return to his previous life. However, what makes 1 Dead in Attic different from other column stories, and, more successful in my opinion, is that Rose appeals to a personal level. He strays away from just stating the facts and allows the reader to experience his own passion and frustration over the course of the months, and, ultimately, give the reader the same sense of loss as he himself experiences. The primary factor in 1 Dead in Attic is the repeating theme of the normalcy of destruction. Rose describes the destruction of the city so frequently and casually that it makes the scene seem almost normal. However, he effectively instates elements that remind the reader of the absolute abnormality of it all and evokes an emotional response. For example, in the following passage, Rose describes an account in which he simply rides a bicycle down the street: “Riding my bike, I searched out my favorite places, my comfort zones. I found that Tatiana’s is still there; and that counts for something. Miss Mae’s and Dick and Jenny’s, ditto. Demilise’s poboy shop is intact, although the sign fell and shattered, but the truth is, that sign needed to be replaced a long time ago. I saw a dead guy on the front porch of a shotgun double on a working-class street, and the only sound was wind-chimes” (Rose 11). Initially, Rose recounts the scenes of the shop in such a casual and matter-of-fact manner that it almost seems normal. The reader becomes accustomed to these scenes of destruction that they almost become just another part of the city. However, Rose immediately inserts the scene about the dead man and the entire passage changes. Although he maintains that sort of normalcy, he inserts an element that is so extraordinary and tragic that it evokes a stronger response from the reader. The reader recognizes that the dead man should not be part of such a normal routine, which gives an even stronger response to want to return to that sense of normalcy. As previously stated, Rose’s success comes from the fact that he reaches out to the reader on a personal level, especially those who have experienced New Orleans firsthand. There were many times in which Rose described an event or place in New Orleans that left me feeling nostalgic for my own childhood or experiences. For example, in one chapter Rose relates a time before the storm when he took his children to see Christmas lights at Al Copeland’s house. As simple as it may be, this scene struck a cord for me. The first thing I thought when I read the scene was Hey I’ve been there! This scene then made me think about all the times my grandpa took us to the house, and made me nostalgic for those times. In these specific descriptions of places or events, Rose appeals to the personal experiences of the reader and evokes an emotional response from theme, as the Christmas scene had for me. Therefore, Rose incorporates the reader into the story and causes him or her to feel that same sense of passion and sadness for the city before the storm. While The Times-Picayune updated citizens on the state of New Orleans during the storm, Chris Rose’s 1 Dead in Attic both described the destruction of the city after the storm while also appealing to the emotional attachment of the reader. Sources: http://www.pulitzer.org/archives/7072 http://www.c-span.org/video/?295195-1/media-coverage-hurricane-katrina http://library.uno.edu/specialcollections/inventories/331.htm http://www.nola.com/katrina/pages/index.ssf/083005 http://www.nola.com/katrina/pages/ http://www.history.com/topics/hurricane-katrina http://newweb.newseum.org/exhibits-and-theaters/previous-exhibits/katrina/videohighlights/katrina-video-jim-amoss.html Book: Rose, Chris. 1 Dead in Attic: After Katrina. New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 2007. Print.