Montenegro – Sector Analysis of the fishery

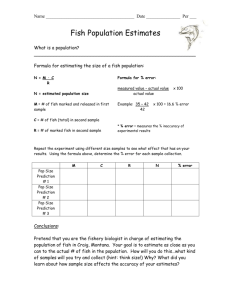

advertisement