The National Museum of the Republic of Korea

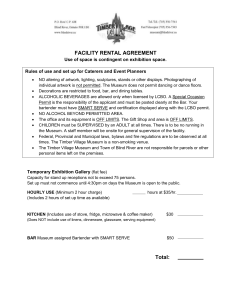

advertisement