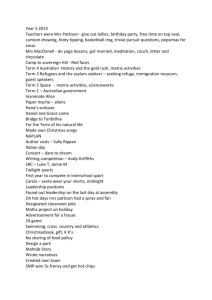

Seoul History: Transactions of the Royal Asiatic Society, 1993

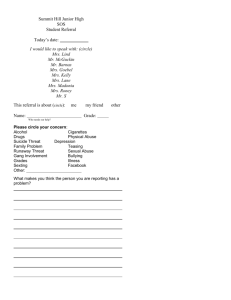

advertisement