a series of moral dilemmas

advertisement

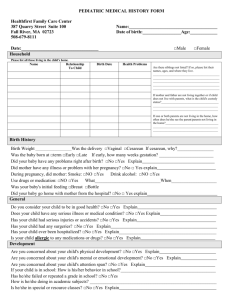

Purvis Society: Dr Sara Paterson-Brown 7 Nov 2013. The Purvis Society was delighted to welcome Dr Sara Paterson-Brown, Consultant Obstetrician and Gynaecologist at Queen Charlotte’s Hospital, London, to the third of this term’s meetings. Her theme was “A Doctor’s Day in the Life of Ethical Challenges” and, with the aid of some excellent slides and prompted by a PowerPoint presentation, she held her large audience in the palm of her hand for well over an hour. She began by introducing herself, and then reminded us that “ethics” effectively represented a code of moral principles derived from a system of values and beliefs; it is the study of ideal conduct that, over the last 30 years (since she did a post-graduate year on “Medical Ethics and the Law”), has changed in the medical world more than one could possibly have imagined. It has become a “code of moral principles derived from a system of values and beliefs and evidence; ideal conduct that changes with time as science advances”. The IVF programme, viewed as morally reprehensible in 1985, is now an accepted and celebrated, treatment for infertility, for instance. Medical decision-making, she informed us, meant that reasoning and judgement are applied to general ethical principles to help to direct one in specific cases, and it is the specific cases that act as a test for the adequacy of our principles. She suggested that one has to expose oneself wholly. For example, “If you don’t agree with euthanasia, don’t avoid the geriatric ward” and “If you agree with it, don’t avoid meeting the doctor asked to do the deed”. Ethical principles were briefly touched upon: the sanctity of life – ‘life is sacred’ but at what cost? Utilitarianism, good versus bad for the greatest number; autonomy – promoting the individual; religious beliefs; rights; the double effect – the end justifies the means; acts and omissions – killing versus not saving. With her audience now fully briefed (and hooked), she embarked upon a series of moral dilemmas, all taken from her long time as a clinician. For example: should a 98-year-old man with severe senile dementia and metastatic cancer who contracts pneumonia be given antibiotics? The audience was divided fairly evenly on this one, but she reminded us that death is sad but inevitable, and that she felt that doctors should not “strive officiously to keep a patient alive”; knowing when to intervene and, equally importantly, when not to is the art of medicine. Pneumonia is viewed as the “old man’s friend”. After this tough start the dilemmas came thick and fast: a 14-year-old girl is seriously ill and requiring urgent major abdominal surgery. She and her parents are Jehovah’s Witnesses and decline any form of blood products, without which this operation is even more hazardous. Can the surgeons go against the parents’ wishes and give her blood to save her life if needed during the surgery? Another: a man comes to see you requesting amputation of his normal left leg. As an amputee he would then avoid having to sign up to go to war. Can the surgeon agree to do this? Another: a baby is due to be born extremely preterm at 24 weeks gestation. If it is born alive the chance of its surviving without brain damage is approximately 30% and the parents are adamant they do not want a brain-damaged child. Should the neonatologist resuscitate the baby? (This was illustrated with possibly the smallest baby any of the audience had ever seen (wrapped in a Sainsbury’s poly bag) with the sweetest little hat on its head…) Upon presenting each dilemma, the audience, with eyes closed, was asked to vote before Dr Paterson-Brown explained, with the utmost clarity, the answer. As might be expected, questions came thick and fast (she had instructed us to interrupt at any stage) and the dilemmas became more challenging. A couple who were both achondroplastic dwarfs came into the antenatal clinic. She was eight weeks pregnant and was concerned to know if her baby would also be an achondroplastic dwarf. If not (yes, if not…), she wanted a termination of pregnancy. Could the doctor agree to this? Or, a foetus is showing signs of serious distress in labour and the mother refuses to let the doctors perform a caesarean section even though the baby is likely to be born dead or damaged. She and her husband say that it “is in God’s hands; He will take care of us”. They also announce the baby is to be named ‘Jesus’. The doctors have to respect the wishes of the mother: to operate would be viewed as a criminal assault... The child, after several days of labour, is born intact! Dr P-B has delivered Jesus and does not know why the child was unaffected. The discussion moved on to the planned termination of a pregnancy. A woman with epilepsy is being managed by medication that is associated with a 5% risk of causing a cleft lip/palate in her baby and requests a termination of pregnancy on account of that risk. Should it be granted? Epilepsy is not a reason for a termination; the possibility that the child would “ruin my life”, apparently, is. Gender selection then reared its ugly head. Apparently is it not impossible to attend one clinic to determine the gender of a child and then visit another to arrange a termination! When an embryo becomes morally significant was a question tackled next. 14 days after conception is the legal cut-off point for research on human embryos (because until then all cells are totipotent), but when does ensoulment occur? Not surprisingly, there is a variety of opinions on this one: according to Aristotle it is at 40 days for men and 80 for women, although the Christian Church proposes that the soul enters a temporary union with the flesh, appearing at birth and surviving death. Surrogacy was our next port of call: a woman is acting as the surrogate mother for a couple. The planned parents provided the gametes for the embryo (IVF) and are the genetic parents. At birth the surrogate decides she wants to keep the baby can she? (Yes she can – it’s more common than you would think.) Or: a woman is acting as the surrogate mother for a couple. The planned parents provided the gametes for the embryo (IVF) and are the genetic parents. At birth the baby is born with abnormalities and the genetic parents change their minds and don’t want the baby any more. Who is responsible for the baby? (It’s the surrogate as she influences the health of the baby – through smoking, drugs, etc.) After these difficult situations (and several others – the pace of the evening was hot!) the audience was faced with one final dilemma: a junior doctor is allowed to ‘go solo’ for his first surgical procedure. Should he tell the patient? Pretty obviously the answer to this is no but Dr P-B then explained some – massively reassuring – detail concerning the training and safeguarding of junior doctors… Finishing with a splendid picture of foetal feet, she came out with the following wonderful statement: “I love feet, baby feet (adult feet are disgusting); if I can see the feet then I have something to get hold of and the baby will be born”. JCEM climbed to his feet to offer his thanks and congratulations, but he need not have bothered. The audience beat him to it; the applause was loud, sincere and long-lasting.