STEMMER Jessica Lee and MAHAR Thomas William

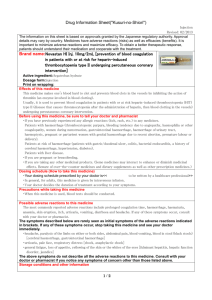

advertisement