Stereotypes and native students Jacqueline Pata, Raven

advertisement

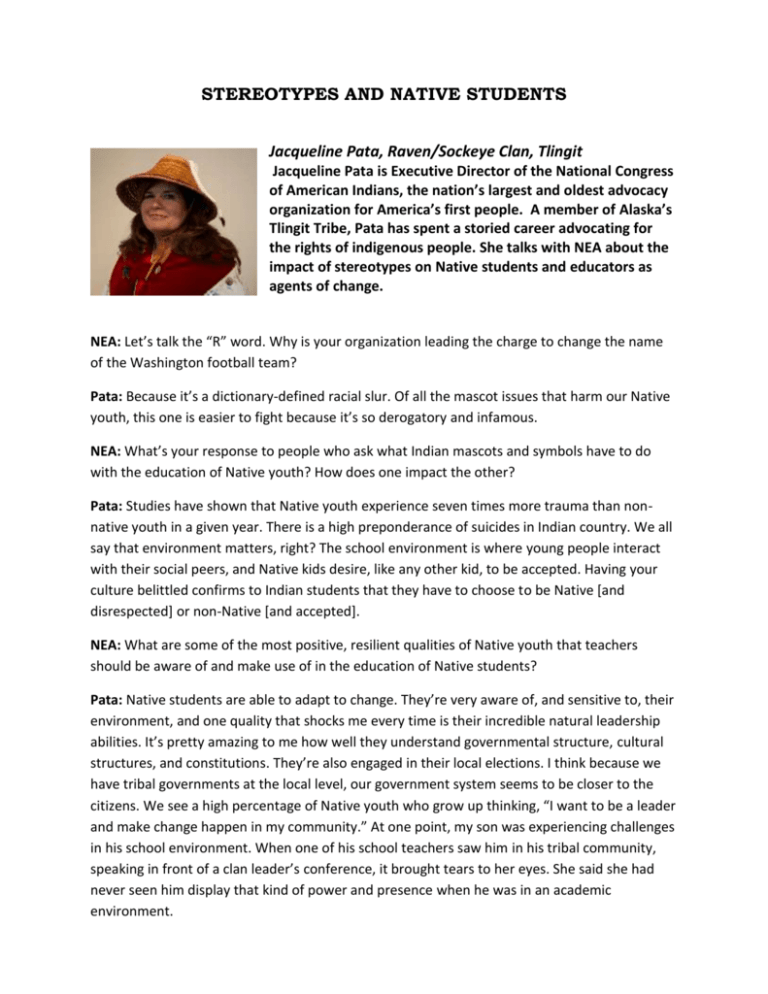

STEREOTYPES AND NATIVE STUDENTS Jacqueline Pata, Raven/Sockeye Clan, Tlingit Jacqueline Pata is Executive Director of the National Congress of American Indians, the nation’s largest and oldest advocacy organization for America’s first people. A member of Alaska’s Tlingit Tribe, Pata has spent a storied career advocating for the rights of indigenous people. She talks with NEA about the impact of stereotypes on Native students and educators as agents of change. NEA: Let’s talk the “R” word. Why is your organization leading the charge to change the name of the Washington football team? Pata: Because it’s a dictionary-defined racial slur. Of all the mascot issues that harm our Native youth, this one is easier to fight because it’s so derogatory and infamous. NEA: What’s your response to people who ask what Indian mascots and symbols have to do with the education of Native youth? How does one impact the other? Pata: Studies have shown that Native youth experience seven times more trauma than nonnative youth in a given year. There is a high preponderance of suicides in Indian country. We all say that environment matters, right? The school environment is where young people interact with their social peers, and Native kids desire, like any other kid, to be accepted. Having your culture belittled confirms to Indian students that they have to choose to be Native [and disrespected] or non-Native [and accepted]. NEA: What are some of the most positive, resilient qualities of Native youth that teachers should be aware of and make use of in the education of Native students? Pata: Native students are able to adapt to change. They’re very aware of, and sensitive to, their environment, and one quality that shocks me every time is their incredible natural leadership abilities. It’s pretty amazing to me how well they understand governmental structure, cultural structures, and constitutions. They’re also engaged in their local elections. I think because we have tribal governments at the local level, our government system seems to be closer to the citizens. We see a high percentage of Native youth who grow up thinking, “I want to be a leader and make change happen in my community.” At one point, my son was experiencing challenges in his school environment. When one of his school teachers saw him in his tribal community, speaking in front of a clan leader’s conference, it brought tears to her eyes. She said she had never seen him display that kind of power and presence when he was in an academic environment. NEA: So that begs the question: How can educators bring forth that same power and presence in a school environment? Pata: Part of that is knowing the students you’re working with, understanding their cultural norms, and being open to seeing other aspects of their strengths—not just viewing them through the lens of classroom structure. NEA: Native students make up a small percentage of the public school student population, which contributes to the AI/AN “invisibility” factor. What about educators who work in schools where there are only a handful, or even no, Native students? What is their responsibility to teach students about American Indian and Alaska Native people and cultures? Pata: Schools can work with Native communities to develop an accurate, inclusive curriculum so students across the country can learn about the history of America’s first people—with resources developed by Native peoples. My own tribe rejected a proposed curriculum because of the inaccuracies, and the school district accepted our recommendations. Our tribal elder designed a curriculum for every grade. He felt that if non-Natives understood us better, they would better accept us. Now non-Native students are not averse to seeing a play that’s all spoken in Tlingit. They’re learning to speak our language based on their exposure in schools. I can see the difference in the last decade, which is just fabulous. It’s a living example of cultural acceptance and understanding and respect. It has changed the kids in our schools. NEA: What is your greatest aspiration for Native students? Pata: I think about this all the time—this is a major passion area for me. Most important, I want our Native youth to not only have hopes and dreams but the options that allow them to achieve those hopes and dreams. NCAI is launching a new initiative called First Kids First, a grassroots movement that supports our youth and creates an environment that allows them to thrive. Our message is: No matter your role in the community, you have a responsibility to the next generation. Native Youth Fast Facts* Native youth under age 25 make up 42 percent of the American Indian and Alaska Native single-race population, while youth make up only 34 percent of the total U.S. population. 1.2 million American Indian and Alaska Native young people are under the age of 25. There is a large population bubble in the 15-19 AI/AN age group. Suicide is the 2nd leading cause of death—and 2.5 times the national rate—for AI/AN youth in the 15-24 age group. High school dropout rates for AI/AN youth are double the national average, according to the Journal of American Indian Education. *National Congress of American Indians and Center for Native American Youth at the Aspen Institute