factors affecting sustainability of goat productivity interventions in

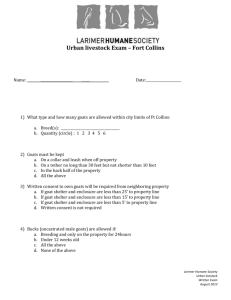

advertisement