PDF - Psychological Sciences

advertisement

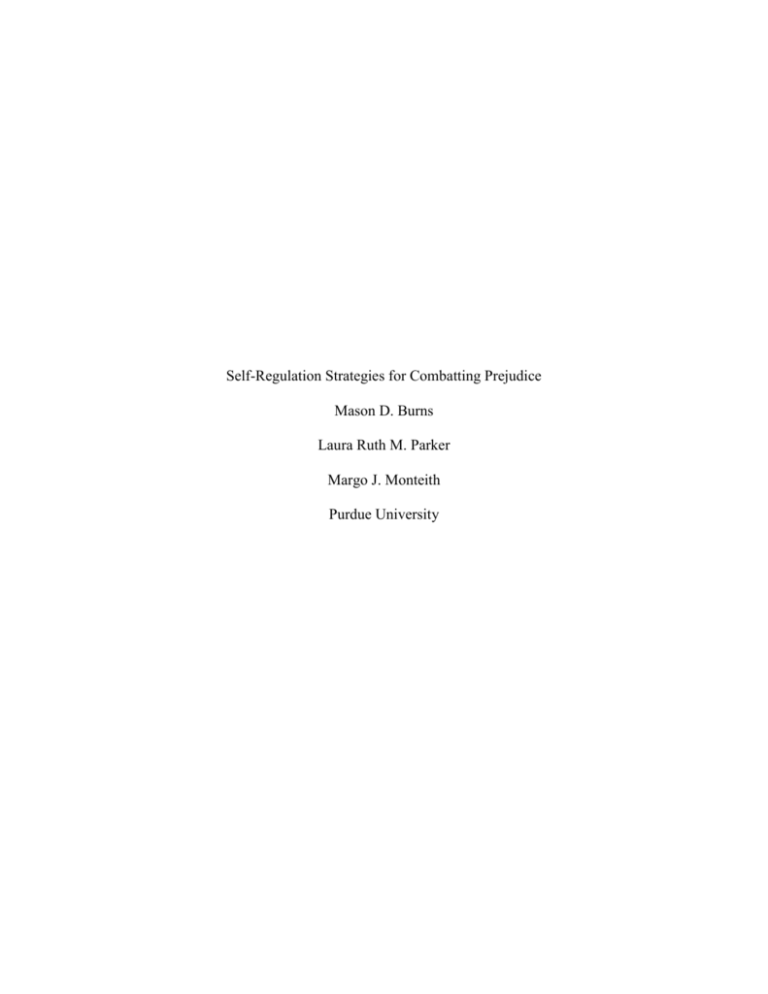

Self-Regulation Strategies for Combatting Prejudice Mason D. Burns Laura Ruth M. Parker Margo J. Monteith Purdue University 2 Abstract Many individuals find themselves having unwanted evaluative or stereotypic biases toward members of disadvantaged or stereotyped groups. Such biases are often subtle in nature and driven by largely unconscious processes, but they result in wide-ranging discriminatory outcomes. How can people effectively reduce their biases? In this chapter, we review various self-regulatory strategies and their impact on prejudice reduction. As a starting point, we discuss various types of motivations for self-regulating intergroup bias. Then, we review a number of self-regulatory strategies, how they operate, and potential consequences. Specifically, we discuss stereotype suppression and colorblindness as strategies aimed at avoiding stereotypical thoughts and ignoring group-based membership, respectively. We discuss the Self-Regulation of Prejudice Model, which entails motivational and learning processes aimed at deautomatizing biased patterns of responding so that egalitarian responses may be generated instead. We also review literature related to the use of implementation intentions to facilitate specific intergroup responses that are unbiased. Although each of these self-regulatory strategies can be useful to some extent, certain strategies have greater ability to produce sustained transformation of subtle biases. Finally, we discuss research related to self-regulation, executive function and intergroup contact, and also how interpersonal confrontations can encourage others to self-regulate. WC: 198 3 In September 2013, police shot and killed Jonathan Ferrell as they responded to a call about a possible “breaking and entering” in a Charlotte, NC neighborhood (King & Stapleton, 2013). Jonathan had been in a serious car accident and sought help after escaping the car through the back window. When he approached a nearby home, the homeowner called ‘911’ and reported that Jonathan was trying to break in. When the police arrived, Jonathan ran toward them, likely disoriented and seeking assistance for his injuries. As he approached, he was shot and killed by an officer on the scene. Why were the homeowner and police officers so quick to assume that Jonathan was dangerous? Would the evening have ended differently if Jonathan were not a young, Black man? Perhaps. The evaluations and judgments of the officers and homeowner were potentially swayed by the subtle but powerful influence of racial biases. Despite the decline in overtly hostile and blatant forms of racial prejudice since the CivilRights movement in the United States, subtle forms of bias remain widespread with pervasive consequences. Data from Project Implicit, an online demonstration website assessing people’s implicit biases, shows that on average people visiting the website demonstrate significant antiBlack bias on a race implicit association task (Nosek, Banaji, & Greenwald, 2002). People also show implicit biases related to other racial groups, and based on gender, religion, and age (Axt, Ebersole, & Nosek, 2014; Nosek et al., 2002). These widely held implicit biases can become activated automatically, without a person’s awareness or intention, and can meaningfully influence people’s evaluations and judgments. For example, as implicit racial bias increased, White doctors were less likely to treat Black patients presenting with symptoms of a heart attack with a potentially life-saving treatment to reduce blood clots (Green, Carney, Palling, Ngo, Raymond, Iezzoni, & Banaji, 2007). In addition, once activated, these subtle biases can influence the responses of people regardless of their levels of explicit, consciously endorsed prejudice. 4 Even people who sincerely endorse egalitarian beliefs and believe themselves to be nonprejudiced may possess and be swayed by subtle biases (e.g., Devine, 1989). If these biases are widely held and influence people’s thoughts, feelings and actions, how can people combat them? People’s biases may conflict with social norms and/or one’s internal standards. If people remain unaware that their thoughts, feelings, and behaviors are inconsistent with personal and societal standards, the bias will live on, unchallenged and unchecked. Alternatively, people may become aware of the conflict between their biased response and societal and personal egalitarian standards. In this case, awareness of the inconsistency may prompt people to attempt to self-regulate their biased responses. In this way, self-regulation has the potential to limit the influence of and ultimately reduce discriminatory outcomes. Self-regulation involves goal setting and applying effort to achieve goals, often through the exertion of self-control (Mischel, 1996). Whether the goal is to study more or eat less, in order to achieve one’s goals, individuals must regulate related thoughts and behaviors. The regulation of both implicit and explicit stereotyping and prejudice is no different. Like all forms of self-regulation, the ability to regulate stereotyping and prejudice requires the detection of discrepancies between one’s goals and actions, the initiation of behaviors to reach one’s goal, assessing one’s progress toward the goal, and adjusting one’s behaviors accordingly (e.g., Carver & Scheier, 1990). While different self-regulatory strategies may involve some unique processes, all regulatory strategies highlight the importance of effort, ability, and motivation. In this chapter, we first discuss the role of motivation in the self-regulation of bias. Then, we turn to discussion of a variety of strategies for self-regulating outgroup bias and their consequences. We review strategies that involve suppressing or blocking stereotypes from the mind and the potential consequences of these strategies. We also discuss motivational and 5 learning processes that facilitate vigilance against biases, inhibition of biases, and ultimately replacement of biases with non-prejudiced responses. Self-regulation can also involve establishing simple if-then statements that can be effective in reducing biased expressions. Following discussion of these self-regulation strategies, we address the consequences of people’s use of self-regulation during interracial interactions, including possible costs to regulators but also advantages for the quality of interactions. Finally, we consider how interpersonal confrontations of biases may spark the self-regulation of prejudice in others. The literature concerning the self-regulation of bias, like the broader literature on stereotyping and prejudice, is marked by an over-representation of research concerning Whites’ bias in relation to Blacks in the United States context. This is due to a variety of factors, including the pervasiveness of this type of bias both historically and contemporarily in the United States. Readers will find that empirical research summarized in this chapter likewise frequently focuses on the regulation of anti-Black bias, although certainly not exclusively. Perhaps more important, we wish to highlight that the theories and strategies relevant to selfregulation that we discuss should apply to intergroup biases broadly as long as the conditions for regulation (e.g., sufficient motivation) have been met. Motivation to Self-Regulate Regardless of the specific self-regulation strategy, the ability to successfully regulate one’s bias depends in large part on one’s motivation to do so. However, the motivation to control prejudice is not a unitary construct that people either have or do not have. Instead, this motivation can come from external and internal sources and vary according to their strength (Plant & Devine, 1998). When motivation to regulate prejudice is primarily external, social norms, fear of disapproval from others, or other pressures from external sources drive self- 6 regulation. However, when motivation to regulate is primarily internal, personal egalitarian beliefs and internal standards drive self-regulation. Low prejudice individuals are often highly internally motivated to regulate prejudice because egalitarianism is personally important to them (e.g., Devine, 1989). Some people are simultaneously motivated by both external and internal sources. Drawing from self-determination theory (e.g., Ryan & Deci, 2000), Legault and colleagues conceptualized motivation to regulate bias on a continuum from non-self-determined to self-determined (Legault, Green-Demers, Grant, & Chung, 2007). Taking a developmental approach, this view of motivation posits that individuals start with no motivation to regulate or respond without bias. This lack of motivation, labeled amotivation, will develop into external regulation as individuals begin to feel external pressures to be egalitarian (e.g., social norms). For people with external regulation, the motivation to reduce prejudiced behaviors stems from self-presentational concerns in specific situations. Over time, individuals may begin to develop affective reactions to self-regulatory failures. Anxiety, guilt, and fear motivate these people to engage in introjected regulation. When individuals start to value egalitarianism as an important societal norm, but before it becomes incorporated into their self-concept, they engage in what is referred to as identified regulation. With the integration of egalitarian values into the selfconcept, people will engage in more self-determined prejudice regulatory efforts, or integrated regulation. Finally, when regulating one’s bias is purely internally driven, inherently satisfying, and a core component of one’s self-concept, people are deemed intrinsically motivated to respond without bias. Motivation to respond without prejudice affects when people will engage in selfregulation, and the effectiveness of their efforts. Because they are attuned primarily to external 7 norms and social pressure, people with less self-determined, more external forms of motivation are more likely to engage in self-regulation only in situations where external forces are relatively strong and salient. On the other hand, people with more self-determined and internal forms of motivation are likely to engage in self-regulation more consistently, and even in the absence of external pressure, because they are driven by their personal, deeply held beliefs and standards to avoid bias (e.g., Plant & Devine, 1998). Furthermore, people with more self-determined, internal motivations to respond without prejudice may be more effective at regulating bias and its negative consequences. Self-determined motivations to regulate prejudice help individuals to buffer the negative impact of intergroup threat, whereas non-self-determined motivations exacerbate the effects of intergroup threat (Legault & Green-Demers, 2012). In addition, when motivation to respond without prejudice was experimentally manipulated, individuals who read brochures emphasizing their personal autonomy in regulating prejudice reported greater selfdetermined motivations and lower levels of both implicit and explicit prejudice relative to individuals who read a brochure emphasizing society’s expectations against prejudice (Legault et al., 2007). Devine, Plant and Amodio (2002) likewise showed that self-reported motivations vary with the ability to control implicit as well as explicit bias. In sum, when people have sufficient motivation, they will engage in efforts to respond without bias. Next, we examine a variety of strategies that people may use to regulate bias. Strategies for Regulating Outgroup Bias Stereotype Suppression When faced with the prospect of having biased thoughts or engaging in biased actions, people may attempt to avoid bias by suppressing any stereotypic thoughts that come to mind. Unfortunately, stereotype suppression often backfires due to an ironic monitoring process in the 8 mind (Macrae, Bodenhausen, Milne, & Jetten, 1994; Wegner, 1994). According to Wegner’s (1994) model of mental control, efforts to actively avoid certain (e.g., prejudiced) thoughts require active monitoring of ongoing thought processes in order to detect and then suppress the unwanted content. This monitoring process subsequently primes individuals with the unwanted thoughts, unfortunately increasing their accessibility. To illustrate, Macrae and colleagues (1994) instructed participants to suppress stereotypic thoughts when writing about a day in the life of a skinhead. On a subsequent writing task, participants who had initially suppressed stereotypic thoughts provided more stereotypic comments about skinheads than participants who did not initially suppress stereotypes (Study 1). Similar effects have been obtained with behavioral measures of stereotyping (Study 2) and stereotype accessibility measures (Study 3). This ironic stereotype rebound also emerges when people self-instigate suppression rather than being explicitly instructed to suppress (Macrae, Bodenhausen, & Milne, 1998). Despite potential pitfalls, stereotype suppression can be effective if people possess internal motivation or sufficient cognitive resources (Monteith, Sherman, & Devine, 1998). People who are internally motivated to avoid stereotyping and/or low in prejudice are less likely to experience stereotype rebound, presumably because they have practice with suppression and accessible nonbiased replacements (Monteith, Spicer, & Tooman, 1998). Stereotype rebound may also be avoided among people who are less practiced at suppression if they possess sufficient cognitive resources to continue monitoring their thoughts following suppression (Gailliot, Plant, Butz, & Baumeister, 2007; Monteith, Spicer et al., 1998; Wyer, Sherman, & Stroessner, 2000). Colorblindness 9 Whereas stereotype suppression involves the active avoidance of stereotypes, colorblindness involves ignoring group-based differences (Goff, Jackson, Nichols, & DiLeone, 2013; Rattan & Ambady, 2013). For example, someone may claim “I don’t see color, I just see people.” Colorblindness may appear to be an easy and straightforward way to avoid prejudice. Unfortunately, colorblindness has limited benefits and many negative consequences. Correll, Park, and Smith (2008) found that strategic colorblindness reduced explicit prejudice, but only short-term. Following a 20-minute delay, adopting a colorblind ideology resulted in a rebound of explicit bias. In addition, participants who adopted a colorblind ideology did not show any differences in implicit bias. Other research similarly suggests that although colorblindness may result in less stereotyping (e.g., Wolsko, Park, Judd, & Wittenbrink, 2000), avoiding racial categorization may actually increase prejudice (Richeson & Nussbaum, 2004), ethnocentrism (Ryan, Hunt, Weible, Peterson, & Casas, 2007), failure to recognize discrimination (Apfelbaum, Pauker, Sommers, & Ambady, 2010), and failure to support programs aimed at discrimination amelioration (Mazzocco, Cooper, & Flint, 2011). Troublingly, strategically ignoring race can impede interracial interactions and cooperative tasks. For example, participants who adopted strategic colorblindness in an interracial interaction were perceived as less friendly by Black interaction partners (Apfelbaum, Sommers, & Norton, 2008). Finally, colorblindness can impair performance on cooperative tasks where the discussion of race can be useful or beneficial (Norton, Sommers, Apfelbaum, Pura, & Ariely, 2006). In sum, although stereotype suppression and colorblindness may be useful forms of prejudice regulation in some cases, these strategies are limited forms of regulation. By requiring individuals to suppress intrusive thoughts of stereotypes or race, these strategies often lead to the ironic increase of these unwanted thoughts. By focusing on preventing thoughts from entering 10 one’s mind, these strategies do not provide individuals with the tools to set long-term egalitarian goals and may fail to produce lasting change. The Self-Regulation Model of Prejudice The Self-Regulation of Prejudice Model (SRP; Monteith, 1993) provides an alternative self-regulatory strategy where individuals actively monitor their environment in order to detect and replace biased thoughts rather than simply ignoring or attempting to suppress them. As shown in Figure 1, the SRP begins by with the well-documented finding that the automatic activation and application of stereotypes is very common, even among individuals who are egalitarian-minded (e.g., Banaji, Hardin, & Rothman, 1993; Bargh, Chen, & Burrows, 1996; Devine, 1989; Greenwald & Banaji, 1995). For people who value egalitarianism and wish to control prejudice because of their personal standards, reliance on stereotypes constitutes selfrelevant discrepancies. Similarly, externally motivated people can experience discrepancies when their biased responses conflict with standards imposed by others (Monteith, Mark, & Ashburn-Nardo, 2010; Monteith, Devine, & Zuwerink, 1993). When individuals become aware of their discrepant responses, the SRP model outlines a series of consequences that facilitate future self-regulatory efforts. According to the SRP, once a biased response is recognized as discrepant with one’s standards, individuals experience increased negative affect. This negative affect is directed toward the self (e.g., guilt and disappointment with the self) if one’s biased response conflicts with internalized personal standards, and is a more generalized discomfort if the biased response violates external standards (see Higgins, 1987). In keeping with motivation and learning theories (Gray, 1982; Gray & McNaughton, 1996), awareness of a discrepant response results in the activation of the behavioral inhibition system (BIS) and in the momentary disruption of ongoing 11 responding. When the BIS is activated, individuals pay more attention to the features of the situation related to the discrepancy, called retrospective reflection. Taken together, these consequences of a discrepant response result in the formation of associations between the discrepancy, stimuli present, and the negative affect experienced – referred to as cues for control. When these cues are present in future situations, they will trigger activation of the BIS. BIS activation causes behavioral inhibition and prospective reflection, prompting a person to pay more attention to their ongoing thoughts and behaviors. This disruption of ongoing responding and increased attention will allow individuals to inhibit prejudiced responses before they occur and generate alternate responses. To illustrate, imagine Andy, a White man, is walking through a crowded mall. Like many people, Andy thinks of himself as a tolerant, fair, and egalitarian person. As Andy is walking, he happens to see a Black man holding a purse. The thought, “I bet he stole that purse” automatically enters Andy’s mind. Just then, he sees a woman emerge from a store, take the purse, and put it over her shoulder. Suddenly, Andy realizes that he stereotyped the Black man as a criminal. Andy might wonder why he had this negative thought. Why did he assume this man was a thief when he was just standing there? Would Andy have responded the same way if the man was White? He feels guilty, and the natural activity of the BIS causes him to momentarily pause and note stimuli in this situation (e.g., his location, what he was doing, the race of the other person, etc.). Upon encountering these cues in the future when a similarly biased response may occur, Andy’s BIS will likely become activated and he will be able to inhibit biased thoughts while maintaining an egalitarian mindset. Empirical Support for the Self-Regulation Model of Prejudice 12 We turn now to an examination of empirical support for each aspect of the SRP model. Central to the SRP is the idea that individuals are capable of detecting discrepancies between their biased responses and their more egalitarian standards for responding. To understand people’s ability to detect discrepancies, researchers have used the Should-Would Discrepancy scale (e.g., Devine, Monteith, Zuwerink, & Elliot, 1991; Monteith, Devine, & Zuwerink, 1993; Monteith & Voils, 1998; Monteith & Mark, 2005). The Should-Would Discrepancy Questionnaire asks participants to rate the extent to which they should act in a biased ways and the extent to which they would act in a biased way across numerous situations. For instance, participants rate the extent they should feel uncomfortable sitting next to a Black person on a bus and the extent to which they would feel uncomfortable doing so. Research using this task consistently demonstrates that many participants report that their shoulds are more prejudiced than their woulds, thus revealing discrepancies. Importantly, people attend to and are aware of discrepancies in their everyday lives. Monteith, Mark, and Ashburn-Nardo (2010) asked White participants to recall and describe past instances in which they thought about, felt about, or behaved toward Blacks in ways that they recognized were discrepant from their either personal standards or social standards. Following this interview, participants completed the Should-Would Discrepancy scale. Most participants reported discrepancy experiences (e.g., feeling afraid of Black men on the subway). In addition, the number of reported discrepancy experiences was positively related to the magnitude of scores on the Should-Would discrepancy scale. Monteith and Voils (1998) examined whether responses on the Should-Would Discrepancy scale predict actual behaviors in situations where one might respond in a prejudiced way. White participants who had completed the Should-Would Discrepancy scale during a separate mass testing procedure were brought to the lab for a study 13 on humor. Participants evaluated many jokes, some of which played on negative stereotypes of Blacks, while experiencing either high or low cognitive load. Low prejudice participants who had reported larger discrepancies between their shoulds and woulds were more likely to positively evaluate racist jokes if they were under high than low cognitive load. However, low prejudice participants with smaller discrepancies evaluated these same racially biased jokes unfavorably even when they were distracted. In other words, participants’ self-reported ability to regulate biased responses corresponded to their actual ability to control biased responding to the racial jokes. Such discrepancy-related findings suggest that individuals are often aware of their outgroup biases that conflict with their standards for responding. Does awareness of discrepancies give rise to affective reactions, as the SRP suggests? Prior research has consistently shown that individuals low in prejudice who experience larger discrepancies when completing the Should-Would scale subsequently report elevated levels of negative self-directed affect, relative to participants with smaller discrepancies. Importantly, this type of affect is critical for consistently motivating subsequent efforts to control prejudice (e.g., Monteith, 1993). Conversely, high-prejudice individuals who experience larger discrepancies when completing the Should-Would Questionnaire subsequently report greater general discomfort, but not greater negative self-directed affect, than their counterparts with smaller discrepancies (e.g., Devine et al., 1991; Monteith et al., 1993). Although discomfort can motivate self-regulation in some situations, it is less likely to do so as consistently as negative self-directed affect. The discrepancy-affect link has been demonstrated in other ways as well. Fehr and Sassenberg (2010) had participants complete an IAT and receive feedback suggesting they held negative attitudes toward Arabs. To the extent that this IAT feedback was discrepant from the 14 individual’s self-standards, participants reported greater guilt and dissatisfaction with themselves (see also Monteith, Voils, & Ashburn-Nardo, 2001). Discrepancy-related affect has also been induced experimentally by leading participants to believe that they have made biased responses (e.g., Monteith, 1993; Monteith Ashburn-Nardo, Voils, & Czopp, 2002). For instance, Amodio, Devine, and Harmon-Jones (2007) provided participants with fixed feedback concerning their neurological reactions in response to viewing images of White, Black, and Asian faces. Participants low in prejudice were led to believe that EEG recordings indicated negative reactions to Black faces relative to White and Asian faces. Following this fixed feedback, participants reported greater guilt relative to baseline levels measured previously. In addition to prompting feelings of guilt, the SRP model posits that awareness of discrepant responses prompts behavioral inhibition, or the disruption of ongoing responses. Monteith, Ashburn-Nardo, Voils, and Czopp (2002) gave low-prejudice, White participants’ fixed physiological feedback suggesting they were reacting negatively to images of Blacks. This feedback caused participants to pause briefly, taking milliseconds longer than a comparison condition to advance to the next screen. Such momentary pauses theoretically facilitate retrospective reflection, or attending closely to features of the environment associated with the discrepancy. Furthermore, this behavioral inhibition serves an important purpose, directing attention to the discrepancy and related information. When the low-prejudice participants in Monteith et al.’s (2002) investigation were asked to list their thoughts about the experiment at the end of the study, participants who believed they had negative reactions to photos of Blacks were significantly more likely to list thoughts associated with their negative feedback, their reactions to the feedback, and race-related topics than participants who believed they had negative reactions to neutral pictures (see also Monteith, 1993). 15 Awareness of discrepant responses leads to feelings of guilt and to behavioral inhibition; however, these outcomes alone are not enough to facilitate effective self-regulation. If Andy from our earlier example simply notices and reflects upon how he behaved in a prejudiced way, he is no less likely to be biased in the future. Rather, in order to change his future behavior he must form associations between the discrepancy, negative affect, and features of the environment to encode cues for control. When he recognizes these relevant cues for control in the future, he be able to inhibit or replace biased responses and prevent another discrepancy from occurring. To examine the development and operation of these cues for control, Monteith (1993, Study 2) gave low-prejudice participants feedback that they were prone to subtly biased homophobic reactions. In an ostensibly separate study, these participants evaluated twelve jokes, two of which were based on stereotypes about gays. Believing that this second task was unrelated to their feedback, the participants recognized the cues they had established previously (e.g., a task dealing with stereotypes of homosexuals) and inhibited their prejudiced responses. Specifically, participants who received discrepant feedback took longer to evaluate these jokes and evaluated the jokes less favorably than participants in a control condition. In other research, low-prejudiced participants complete a race-based IAT and received bogus feedback that they were biased against Blacks (Monteith et al., 2002). In a second supposedly unrelated task, participants were presented with a single word one-at-a-time and were asked to indicate whether they liked or disliked each word. Embedded among fillers were traditionally Black names that had also been used earlier in the IAT. To the extent that participants experienced guilt following IAT feedback, they took longer to evaluate the Black names (prospective reflection) and evaluated them more favorably. 16 The process of generating alternatives to prejudiced responses can involve replacement with non-biased responses, as in the examples above, or other processes. For instance, people may gather more information and individuate outgroup members (e.g., Fiske & Neuberg, 1990; Fiske, Lin, & Neuberg, 1999) or initiate positive intergroup contact (e.g., Esses & Dovidio, 2002) as a means to generating non-biased responses. Before concluding this section, we wish to underscore that self-regulating prejudice through the steps outlined by the SRP model applies well to low-prejudice individuals who personally value egalitarianism. However, the SRP model can also apply to high-prejudice individuals who are externally motivated to control their prejudice. For instance, when White participants were led through a guided interview concerning the development of cues for control, one high-prejudice participant reported: My roommate’s Black and sometimes when we’re watching shows they kinda like make the Blacks look trashy, you know like on Jerry Springer… I was laughing at it but he wasn’t really and it kind of automatically made me feel like I had done something wrong so I felt bad… I didn’t want him to think, “Well he looks like some kind of racist. When asked about future concern and intent to regulate, the same participant responded: If something on TV comes up that’s like shady you know it’s like I think about it… you know I think about it to make sure that it doesn’t happen again in case he actually was mad about it. I wouldn’t laugh out loud if I thought maybe it would be offensive to someone else. I’m just a little more careful now (Monteith et al., 2010). Through external pressures such as those reported by this one participant, the SRP can help explain how individuals high in prejudice establish cues for control - albeit for external reasons. Implementation Intentions For people to successfully self-regulate, they must be able to recognize cues that lead to prejudice responses. Upon acknowledging these situational features, people can take steps to prevent themselves from falling into similar prejudiced patterns of behavior in the future. By 17 establishing implementation intentions (Fujita, 2011; Gollwitzer, 1999; Gollwitzer & Sheeran, 2006) people form specific “if-then” plans of action to follow when they encounter a specific cue for control. In the case of regulating prejudice, an individual might form the if-then plan: “If I see a Black person at the mall, then I will think this person is shopping.” When such implementation intentions are formed, the cues activating these statements (i.e., seeing a Black person at the mall) become more salient and the intended then response (i.e., assuming the person is shopping) occurs more quickly, reflexively (Gollwitzer & Brandstätter, 1997), and with less effort (Bayer, Achtziger, Gollwitzer, & Moskowitz, 2009). As a means of regulating bias, implementation intentions can be useful by defining desired outcomes. For example, Stewart and Payne (2008) instructed participants to form the implementation intention to think “good” when they saw a Black person during a race-IAT or to think “safe” when engaging in the weapon-identification task (a task assessing implicit associations between weapons versus neutral objects with Whites and Blacks; Payne, 2001). Forming this simple implementation intention significantly reduced automatic stereotype bias on both tasks. Similarly, Mendoza, Gollwitzer, and Amodio (2010) investigated how implementation intentions affect responding on the Shooter Bias Task (Correll, Park, Judd, & Wittenbrink, 2005). The Shooter Bias Task is a computerized program where participants are instructed to “shoot” when an image of an armed person appears and “not shoot” when an image of an unarmed person appears. Previous research demonstrates a consistent bias where people incorrectly shoot unarmed Black targets more frequently than unarmed White targets. Participants given the implementation intention to ignore the race of the target or to focus on whether the person was armed or not made fewer errors than those without such implementation intentions. 18 Due to the specificity of if-then statements, forming specific implementation intentions may not have generalized bias reductions effects. That is, although forming the implementation intention “If I see a Black person at the mall, I will think they are shopping” may help in the context of a mall or shopping centers, this implementation intention may be ineffective across more diverse situations. Additionally, broader implementation intentions such as, “If I see a Black person, then I will ignore their race” may result in ironic negative consequences (Apfelbaum et al., 2008; Apfelbaum et al., 2010; Vorauer, Gagnon, & Sasaki, 2009). Nonetheless, implementation intentions can be used effectively in conjunction with other regulatory strategies. For instance, once a cue for control has been identified, pairing this cue with an implementation intention to think carefully before responding can help slow down automatic responding and encourage people to take in more information before engaging in a behavior (Mendoza et al., 2010). Self-Regulation, Executive Function, and Intergroup Contact All of the self-regulation strategies discussed in this chapter require effort. Monitoring one’s thoughts and behaviors, paying attention to cues in the environment, and inhibiting prejudiced responses can be taxing. Because both implicit and explicit bias can affect how interracial interactions are experienced by both White and Black interaction members (Dovidio, Kawakami, & Gaertner, 2002), effective regulation is needed. However, cognitive depletion due to effortful regulation may reduce the quality of the interracial interaction. Consistent with this possibility, many of the problems Whites experience in interracial interactions stem from their desire to appear nonprejudiced, their desire to avoid offending interaction partners, and their uncertainty about the best way to achieve these positive outcomes (Apfelbaum et al., 2008; Plant, 2004; Richeson & Shelton, 2007). 19 Richeson and Shelton (2003) examined some of the difficulties associated with regulation during interracial interactions by measuring Whites’ implicit racial attitudes (via the IAT) prior to an interaction with a White or a Black experimenter. Interestingly, Whites higher in implicit bias demonstrated more positive nonverbal behaviors toward their Black interaction partner relative to Whites lower in bias. Following the interaction, participants completed a measure of cognitive depletion. Because interracial interactions require a great deal of self-regulation among individuals higher in implicit racial bias, these participants experienced greater cognitive impairment after interacting with a Black, but not White, experimenter. Increased regulatory efforts have also been induced experimentally through manipulating concern with appearing prejudiced. In one line of research, White participants complete a raceIAT before being randomly assigned to a prejudice concern condition or a control condition (Richeson & Trawalter, 2005). Participants in the prejudice concern condition received IAT feedback telling them that “most people are more prejudiced than they think they are.” Participants then interacted with either a White or Black interaction partner and completed a measure of cognitive depletion. Participants induced to be more concerned about prejudice prior to the interaction experienced greater self-regulatory demands and suffered greater cognitive depletion if they interacted with a Black partner than if they interacted with a White partner. Though interracial interactions can be cognitively depleting, research points to a number of strategies to help reduce depletion associated with self-regulation. For instance, individuals who adopt an approach or promotion mindset are less depleted following self-regulation relative to individuals who adopt avoidance or prevention mindsets (Oertig, Schuler, Schnelle, Bandstätter, Roskes, & Elliott, 2013; Trawalter & Richeson, 2006). In addition, research from the broader self-regulation literature suggests that positive affect (Tice, Baumeister, Shmeuli, & 20 Muraven, 2007), regulatory practice (Gailliot et al., 2007), and the use of implementation intentions can reduce depletion following self-regulation (Webb & Sheeran, 2003). Inroads to Self-Regulation: Interpersonal Confrontations Even if individuals are motivated and able to self-regulate their biases, they may not always notice their own biased responses. By pointing out biases, interpersonal confrontations may encourage bias regulation. Czopp, Monteith, and Mark (2006) examined the self-regulatory consequences of interpersonal confrontations of prejudice. At the beginning of the study, participants generated inferences about individuals based on a single photograph and a small amount of information about the person. For example, participants saw a picture of a White man and the description “This person works with numbers.” Participants then freely generated a description of this person such as “accountant” or “math teacher.” Embedded within 20 photograph-description pairs were critical trials with a photograph of a Black man paired with descriptions likely to yield a stereotypic response (e.g., “This person can be found behind bars” might elicit the response “criminal” rather than a nonstereotypic alternative such as “bartender”). Then some participants were confronted about their stereotype-consistent responses. Following the confrontation, participants reported greater guilt and self-disappointment, and provided significantly fewer stereotypic responses on a later stereotype inference task than non-confronted participants (Czopp et al., 2006). Confrontations are more or less effective at reducing bias depending on the type of bias confronted and characteristics of the confronter. For instance, confrontations of racism are often effective in reducing subsequent racially biased responses. However, people may view confrontations of sexism as illegitimate or unnecessary because social norms against sexism are weaker than those against racism (Fiske & Stevens, 1993) and gender stereotypes are often 21 perceived as positive (Czopp & Monteith, 2003). Indeed, research directly comparing confrontations of racism and sexism find that confrontations of gender bias result in less guilt, less corrective behaviors, less concern, and greater amusement relative to confrontations of racism (Czopp & Monteith, 2003; Gulker, Mark, & Monteith, 2013). Characteristics of the confronter similarly influence the efficacy of a confrontation. For instance, while nontargets (e.g., males who confront sexism toward women) may have difficulty recognizing bias or may not feel comfortable confronting racism or sexism, these confrontations may be more effective than confrontations by target group members (Czopp & Monteith, 2003; Drury & Kaiser, 2014; Gulker et al., 2013; Rasinski & Czopp, 2010; Saunders & Senn, 2009). Because confronting sexism/racism has no apparent benefit for men/Whites, nontarget confrontations are perceived as less self-interested and more persuasive (Drury & Kaiser, 2014; Gervais & Hillard, 2014; Gulker et al., 2013). Finally, beyond bringing to light one’s own biases, confrontations also help encourage self-regulation by creating egalitarian norms and expectations of others. These norms may then help motivate individuals with egalitarian self-concepts to live up to these standards and regulate negative thoughts and behaviors in the future (e.g., Blanchard, Crandall, Brigham, & Vaughn, 1994; Blanchard, Lilly, & Vaughn, 1991; Monteith, Deneen, & Tooman, 1996). Conclusion As we’ve seen in this chapter, the accumulated evidence of people’s ability to successfully regulate stereotypes and prejudice demonstrates that bias can be tamed. Although there are several strategies that may help people regulate their bias, some strategies are more effective than others at promoting long term reduction of bias across a variety of situations. Furthermore, people’s internal and external motivations to respond without prejudice play a role 22 in the effectiveness of their efforts to respond without bias. Importantly, self-regulation strategies can have important consequences for people’s lives, as demonstrated by the reviewed literature on self-regulation and interracial interactions. Although we believe self-regulation is an effective and useful means for reducing prejudice, it is no silver bullet. In order to successfully combat bias, people must first be aware of the need for self-regulation of bias. For this reason, interpersonal confrontations of prejudice are an effective way to jump start the self-regulatory process in others. Confrontations not only increase people’s awareness of their own biased responses, but also decrease the likelihood that they will make the same biased response in the future. Beyond awareness of the need for selfregulation, people need to know how to implement effective strategies to achieve control, and need to be sufficiently motivated to practice self-regulatory strategies with consistency and persistence. These factors stand between the capability for and the realization of successful selfregulation. To the extent that subtle bias contributes to ongoing inequality and discrimination, selfregulation strategies provide useful tools for combatting both subtle bias and its pernicious consequences. Once again, the tragic death of Jonathan Ferrell has raised concerns in the eyes of the public that subtle biases may contribute to harsher and more punitive treatment of young, Black men at the hands of police officers. Sadly, this is not the only event of police shootings involving Blacks where racial biases have been implicated. The deaths of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Sandra Bland and other young Black Americans have all led to greater media coverage of and public attention toward persisting racial prejudice and inequality in the U.S. For example, in his piece published in the wake of Michael Brown’s death, “The Science of Why Cops Shoot Young Black Men,” Chris Mooney explored the role implicit bias may play in the 23 shooting deaths of Black men and women at the hands of the police. Although retroactively determining whether race actually did play a role in these types of situations is not possible, we do know from the vast literature that intergroup biases, often very subtle in nature and unintended, continue to support unequal playing fields and disparate outcomes. Efforts to raise awareness of and teach strategies for effective self-regulation are sorely needed due to the persistence of subtle bias and the potential of self-regulation to stop bias in its tracks. 24 References Amodio, D. M., Devine, P. G., & Harmon-Jones, E. (2007). A dynamic model of guilt: Implications for motivation and self-regulation in the context of prejudice. Psychological Science, 18, 524-530. Apfelbaum, E. P., Pauker, K., Sommers, S. R., & Ambady, N. (2010). In blind pursuit of racial equality? Psychological Science, 21, 157-1592. Apfelbaum, E. P., Sommers, S. R., & Norton, M. I. (2008). Seeing race and seeming racist? Evaluating strategic colorblindness in social interaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 918-932. Axt, J.R., Ebersole, C.R., & Nosek, B.A. (2014). The rules of implicit evaluation by race, religion, and age. Psychological Science, 25, 1804-1815. Banaji, M. R., Hardin, C., & Rothman, A. J. (1993). Implicit stereotyping in person judgment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 272-281. Bargh, J. A., Chen, M., & Burrows, L. (1996). Automaticity of social behavior: Direct effects of trait construct and stereotype activation on action. Journal of Personality and social Psychology, 71, 230-244. Bayer, U. C., Achtziger, A., Gollwitzer, P. M., & Moskowitz, G. (2009). Responding to subliminal cues: Do if-then plans facilitate action preparation and initiation without conscious intent? Social Cognition, 27, 183-201. Blanchard, F. A., Crandall, C. S., Brigham, J. C., & Vaughn, L. A. (1994). Condemning and condoning racism: A social context approach to interracial settings. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79, 993-997. 25 Blanchard, E. A., Lilly, T., & Vaughn, L. A. (1991). Reducing the expression of racial prejudice. Psychological Science, 2, 101-105. Carver, C. S., & Scheier, M. F. (1990). Origins and functions of positive and negative affect: A control-process view. Psychological Review, 97, 19-35. Correll, J., Park, B., Judd, C. M., & Wittenbrink, B. (2002). The police officer’s dilemma: Using ethnicity to disambiguate potentially threatening individuals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 83, 1314-1329. Correll, J., Park, B., & Smith, J. A. (2008). Colorblind and multicultural prejudice reduction strategies in high-conflict situations. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 11, 471491. Czopp, A. M., & Monteith, M. J. (2003). Confronting prejudice (literally): Reactions to confrontations of racial and gender bias. Personality and social Psychology Bulletin, 29, 532-544. Czopp, A. M., Monteith, M. J., & Mark, A. Y. (2006). Standing up for a change: Reducing bias through interpersonal confrontation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90, 784-803. Devine, P. G. (1989). Stereotypes and prejudice: Their automatic and controlled components. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56, 5-18. Devine, P. G., Monteith, M. J., Zuwerink, J. R., & Elliot, A. J. (1991). Prejudice with and without compunction, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 817-830. Devine, P.G., Plant, E.A., & Amodio, D.M. (2002). The regulation of explicit and implicit race bias: The role of motivations to respond without prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 835-848. 26 Dovidio, J. F., Kawakami, K., & Gaertner S. L. (2002). Implicit and explicit prejudice and interracial interactions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 62-68. Drury, B. J., & Kaiser, C. R. (2014). Allies against sexism: The role of confronting sexism. Journal of Social Issues, 70, 637-652. Esses, V. M., & Dovidio, J. F. (2002). The role of emotions in determining willingness to engage in intergroup contact. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 1202-1214. Fehr, J., & Sassenberg, K. (2010). Willing and able: How internal motivation and failure help to overcome prejudice. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 13, 167-181. Fiske, S. T. & Neuberg, S. L. (1990). A continuum of impression formation, from categorybased to individuating processes: Influences of information and motivation on attention and interpretation. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 23, 1-74. Fiske, S. T., & Stevens, L. E. (1993). What’s So Special About Sex? Gender Stereotyping and Discrimination. Sage Publications, INC. Fiske, S. T., Lin, M., & Neuberg, S. (1999). The continuum model. Dual-Process Theories in Social Psychology, 231-254. Fujita, K. (2011). On conceptualizing self-control as more than the effortful inhibition of impulses. Personality and social Psychology Review, 15, 352-366. Gailliot, M. T., Plant, E. A., Butz, D. A., & Baumeister, R. F. (2007). Increasing self-regulatory strength can reduce the depleting effect of suppressing stereotypes. Personality and Social Psychological Bulletin, 33, 281-294. Gervais, S. J. & Hillard, A. L. (2014). Confronting sexism as persuasion. Effects of a confrontations’ recipient, source, message, and context. Journal of Social Issues, 70, 653667. 27 Goff, P. A., Jackson, M. C., Nichols, A. H., & DiLeone, B. A. L. (2013). Anything but race: Avoiding racial discourse to avoid hurting you or me. Psychology, 4, 335-339. Gollwitzer, P. M. (1999). Implementation intentions: Strong effects of simple plans. American Psychologist, 54, 493-503. Gollwitzer, P. M., & Brandstätter, V. (1997). Implementation intentions and effective goal pursuit. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73, 186-199. Gollwitzer, P. M., & Sheeran, P. (2006). Implementation intentions and goal achievement: A meta-analysis of effects and processes. In M.P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (pp. 60-119). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. Gray, J. A. (1982). The neuropsychology of anxiety: An enquiry into the functions of the septohippocampal system. New York: Oxford University Press. Gray, J. A., & McNaughton, N. (1996). The neuropsychology of anxiety: Reprise. In Hope, D.A. (Ed.), Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 1995: Perspectives on anxiety, panic, and fear. Current theory and research in motivation, Vol. 43. (pp. 61-134). Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. Green, A. R., Carney, D. R., Palling, D. J., Ngo, L. H., Raymond, K. L., Iezzoni, L. I., Banaji, M. R. (2007). Implicit bias among physicians and its prediction of thrombolyosis decision for black and white patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 22, 1231-1238. Greenwald, A. B., & Banaji, M. R. (1995). Implicit social cognition: Attitudes, self-esteem, and stereotypes, Psychological Review, 102, 4-27. Gulker, J. E., Mark, A. Y., & Monteith, M. J. (2013). Confronting prejudice: The who, what, and why of confrontation effectiveness. Social Influence, 8, 280-293. 28 Higgins, E. T. (1987). Self-discrepancy theory: A theory relating self and affect. Psychological Review, 94, 319-340. King, J., & Stapleton, A. (2013, September 9). Charlotte police kill ex-FAMU player who may have been running to them for help, CNN. Retrieved from http://edition.cnn.com/ 2013/09/15/justice/north-carolina-police-shooting/ Legault, L., & Green-Demers, I. (2012). The protective role of self-determined prejudice regulation in the relationship between intergroup threat and prejudice. Motivation and Emotion, 36 143-158. Legault, L., Green-Demers, I., Grant, P., & Chung, J. (2007). On the self-regulation of implicit and explicit prejudice: A self-determination theory perspective. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33, 732-749. Macrae, C. N., Bodenhausen, G. V., & Milne, A. B. (1998). Saying no to unwanted thoughts: Self-focus and the regulation of mental life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 578-589. Macrae, C. N., Bodenhausen, G.V., Milne, A. B., & Jetten, J. (1994). Out of mind but back in sight: Stereotypes on the rebound. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 808-817. Mazzocco, P. J., Cooper, L. W., & Flint, M. (2012). Different shades of racial colorblindness: The role of prejudice. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 15, 167-178. Mendoza, S. A., Gollwitzer, P. M., & Amodio, D. M. (2010). Reducing the expression of implicit stereotypes: Reflexive control through implementation intentions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 46, 512-523. 29 Mischel, W. (1996). From good intentions to willpower. In P.M. Gollwitzer & J.A. Bargh (Eds.), The psychology of action: Linking cognition and motivation to behavior (pp. 197218). New York: Guilford Press. Monteith, M. J. (1993). Self-regulation of prejudiced responses: Implications for progress in prejudice reduction efforts. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 469-485. Monteith, M. J., Ashburn-Nardo, L., Voils, C. I., & Czopp, A. M. (2002). Putting the brakes on prejudice: On the development and operation of cues for control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83, 1029-1050. Monteith, M. J., Deneen, N. E., & Tooman, G. D. (1996). The effect of social norm activation on the expression of opinions concerning gay men and Blacks. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 18, 267-287. Monteith, M. J., Devine, P. G., & Zuwerink, J. R. (1993). Self-directed versus other-directed affect as a consequence of prejudice-related discrepancies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64, 198-210. Monteith, M. J., & Mark, A. Y. (2005). Changing one’s prejudice ways: Awareness, affect, and self-regulation. European Review of Social Psychology, 16, 113-154. Monteith, M. J., Mark, A.Y., & Ashburn-Nardo, L. (2010). The self-regulation of prejudice: Toward understanding its lived character. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 13, 183-200. Monteith, M. J., Sherman, J., & Devine, P. G. (1998). Suppression as a stereotype control strategy. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 2, 63-82. 30 Monteith, M. J., Spicer, C. V., & Tooman, G. (1998). Consequences of stereotype suppression: stereotypes on and not on the rebound. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 34, 355-377. Monteith, M. J., & Voils, C. I. (1998). Proneness to prejudiced responses: Toward understanding the authenticity of self-reported discrepancies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 901-916. Monteith, M. J., Voils, C. I., & Ashburn-Nardo L. (2001). Taking a look underground: Detecting, interpreting, and reacting to implicit racial biases. Social Cognition, 19, 365417. Mooney, C. (2014, December). The science of why cops shoot young black men: And how to reform our bigoted brains. Mother Jones. Retrieved from http://www.motherjones.com/ politics/2014/11/science-of-racism-prejudice Norton, M. I., Sommers, S. R., & Apfelbaum, E. P., Pura, N., & Ariely, D. (2006) Color blindness and interracial interactions: Playing the political correctness game. Psychological Science, 17, 949-953. Nosek, B. A., Banaji, M. R., & Greenwald, A. G. (2002). Harvesting implicit group attitudes and beliefs from a demonstration website. Group Dynamics and Intergroup Relations, 6, 101115. Oertig, D., Schüler, J., Schnelle, J., Brandstätter, V., Roskes, M., & Elliot, A. J. (2013). Avoidance goal pursuit depletes self-regulatory resources. Journal of Personality, 81, 365-375, Payne, B. K. (2001). Prejudice and perception: The role of automatic and controlled processes in misperceiving a weapon. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81, 181-192. 31 Plant, E. A. (2004). Responses to interracial interactions over time. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 1458-1471. Plant, E. A., & Devine, P. G. (1998). Internal and external motivation to respond without prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 811-832. Plant, E. A., & Devine, P. G. (2008). Interracial interactions: Approach and avoidance. In A. J. Elliot, A. J. Elliot (Eds.), Handbook of approach and avoidance motivation (pp. 571-584). New York, NY, US: Psychology Press. Rasinski, H. M. & Czopp, A. M. (2010). The effect of target status on witnesses’ reactions to confrontations of bias. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 32, 8-16. Rattan, A., & Ambady, N. (2013). Diversity ideologies and intergroup relations: An examination of colorblindness and multiculturalism. European Journal of Social Psychology, 43, 1221. Richeson, J. A., & Nussbaum, R. J. (2004). The impact of multiculturalism versus colorblindness on racial bias. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 40, 417-423. Richeson, J. A., & Shelton, J. N. (2007). Negotiating interracial interactions: Costs, consequences, and possibilities. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16, 316320. Richeson, J. A., & Shelton, J. N. (2003). When prejudice does not pay: Effects of interracial contact on executive function. Psychological Science, 14, 287-290. Richeson, J. A., & Trawalter, S. (2005). Why do interracial interactions impair executive function? A resource depletion account. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 934-947. 32 Ryan, E. L., & Deci, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11, 227-268. Ryan, C. S., Hunt, J. S., Weible, J. A., Peterson, C. R., & Casas, J. F. (2007). Multicultural and colorblind ideology, stereotypes, and ethnocentrism among Black and White Americans. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 10 617-637. Saunders, K. A., & Senn, C. Y. (2009). Should I confront him? Men’s reactions to hypothetical confrontations of peer sexual harassment. Sex Roles, 61, 399-415. Stewart, B. D., & Payne, B. K. (2008). Bringing automatic stereotyping under control: Implementation intentions as efficient means of thought control. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34, 1332-1345. Tice, D. M., Baumeister, R. F., Shmueli, D., & Muraven, M. (2007). Restoring the self: Positive affect helps improve self-regulation following ego depletion. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43, 379-384. Trawalter, S., & Richeson, J. A. (2006). Regulatory focus and executive function after interracial interactions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 42, 406-412. Vorauer, J. D., Gagnon, A., & Sasaki, S. J. (2009). Salient intergroup ideology and intergroup interaction. Psychological Science, 20, 838-845. Webb, T. L., & Sheeran, P. (2003). Can implementation intentions help to overcome egodepletion? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 39, 279-286. Wegner, D. M. (1994). Ironic processes of mental control. Psychological Review, 101, 34-52. Wolsko, C., Park, B., Judd, C. M., & Wittenbrink, B. (2000). Framing interethnic ideology: Effects of multicultural and color-blind perspectives on judgments of groups and individuals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78, 635-354. 33 Wyer, N. A., Sherman, J. W., & Stroessner, S. J. (2000). The roles of motivation and ability in controlling the consequences of stereotype suppression. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26, 13-25. 34 Automatic Stereotype Activation and Use Cues for Control Present When Discrepant Response is Possible Discrepant Response • behavioral inhibition Awareness of Discrepant Response • prospective reflection • negative self-directed affect • behavioral inhibition • retrospective reflection establish cues for control Figure 1: The Self-Regulation of Prejudice Model inhibit prejudiced response and generate alternative response