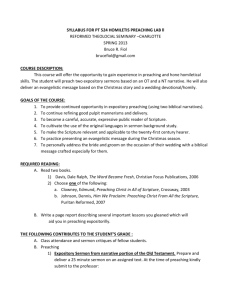

Introduction to Homiletics November 5, 2013

advertisement

Introduction to Homiletics November 5, 2013 Lesson Plan Turn in Sermon Notes from Resources Mid-Term Examination Return Brooding and Sermon Evaluations Review Sermon Evaluations Learning Objective: Students will understand the advantages and occasions of various preaching techniques including introduction, transition, illustration, application, zinger, and conclusion. Learning the process of preaching consists primarily of two things: principles and techniques. So far during this semester we have focused on the more important of the two which is principles. Principles of preaching capture the theology and ideals of preaching. The second, though less important, aspect is preaching techniques. Preaching techniques are the tools preachers use, in the sermon, to gather hearers’ attention, emphasize main points, help the hearer understand where they are in the sermon and where the sermon is going. Introduction: Be sure you have something to introduce. Introduction is important because it can be extremely powerful in gathering the attention of the hearers. So, make sure your introduction gathers their attention. It should answer the question “Why should I listen to this sermon?” Use pathos here. If you start with the Bible, get to “life today” as quickly as possible. If you start with life today, get to the text as quickly as possible. Give the audience a clue about where the sermon is heading. The introduction should establish the tone. Don’t start with humor and then preach about pain. Introductions should take no more than 10% of the sermon time. Some preachers believe the introduction should “surface a need.” The Homiletical Plot is a prime example. Others say you should start with talk about everyday life that the hearers can identify with. I agree with many homileticians who say that introductions should be written last—after the rest of the sermon is complete. Transition Transitions help your audience know when you have finished talking about “A” and are preparing to move on to “B.” Without the transition, the audience is trying to connect “B” material/words with “A.” Transitions can help the audience track with where the sermon is heading. Body movement and pauses can be helpful in transitions. Transitions can be simple and brief like, “The struggle of the ancient Israelites in exile is much like our struggle today.” That finishes the section explaining exile and introduces talking about life today. Transitions can be as long as a paragraph as you explain the connections between ancient exilic Israel and today. If you hop from one sections to the next, you haven’t transitioned well. In a deductive (three points) sermon, you can finish your first point, repeat your first point, and then say, “second…” and state your second point. TECT | Introduction to Homiletics, Rev. David Bonnet, 5 November 2013 1 Illustration Illustrations are used to shine light on important points. They should make the main points more clear. They should not be the focus of the sermon. Illustrations should not outshine the main points. An illustration has failed if people remember the illustration but don’t remember the assertion/point it illustrated. Illustrations should serve the sermon. DO NOT build a sermon around a great illustration. Great illustrations options include: historical events, fictional stories, fables, modern retellings, biblical quotes (especially Proverbs), wise saying, quotes by historical figures, examples from everyday life, songs. Application One day, President Abraham Lincoln was walking home from church. A man asked him how he enjoyed the sermon. He said, it was sufficient but not extraordinary.” When asked why not Lincoln replied, “The sermon didn’t ask me to do anything great.” This story shows the importance of sermons to challenge the hearer to DO something. The preacher has asserted/stated an important truth. She has explained that truth well. She has illustrated the assertion and therefore made it clear. Now she must tell the hearers exactly what it means for their lives— what they must DO because that particular truth is true. Some application is making a decision. Some application is visible response. Most application is life change during regular tasks of life in the home, at work, and in leisure time. Help the hearer understand exactly what the truth, if applied in his life, would look like. Zinger Zingers can be a powerful tool for driving home a point. A zinger is a bold statement, so shocking, that it forces the hearers into thoughtful reflection. Examples: God loves to love the people you and I love to hate. Honestly, I want King David to go to hell. Submission is a love word, not a control word. Zingers should not be used in every sermon lest they lose their impact. Zingers can, though rarely, be used as a sermon refrain. Refrain A refrain, as in hymnody, is a phrase or series of phrases that are repeated for emphasis. Consider the song Blessed Assurance. We remember the refrain, “This is my story, this is my son: praising my Savior all the day long.” The refrain can link a sermon together and provide emphasis on the main point. It can be twisted at the end for a powerful new emphasis. Examples: Acts 2: When the Holy Spirit shows up, everything changes! 2 Samuel 11-12: What happed with David can happen with all of us. Luke 3:21: Next! Conclusion Be sure you have something to conclude! A sufficient, but not great conclusion simply repeats the main points of the sermon. A better conclusion, takes everything in the sermon, argues for their implication, challenges the listener to action, and paints the picture of what life looks like when the Church embraces the truth and challenge of the sermon. Conclusion is an ideal place for the pathos part of your sermon. Use emotion to challenge the hearers. TECT | Introduction to Homiletics, Rev. David Bonnet, 5 November 2013 2