docx

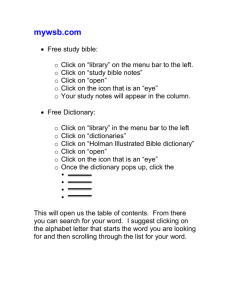

advertisement